Salvatore Ferragamo Silk Museum

For five thousand years, the thin, shiny thread generated by lepidoptera slime has been used to make the most beautiful of fabrics, a symbol of royalty, elegance and luxury.

Since the Middle Ages, Italy has distinguished itself in the manufacture of silk fabrics. In the 1930s, Como emerged as the pre-eminent location in the country for creating printed products, playing an important role in Made in Italy’s international success.

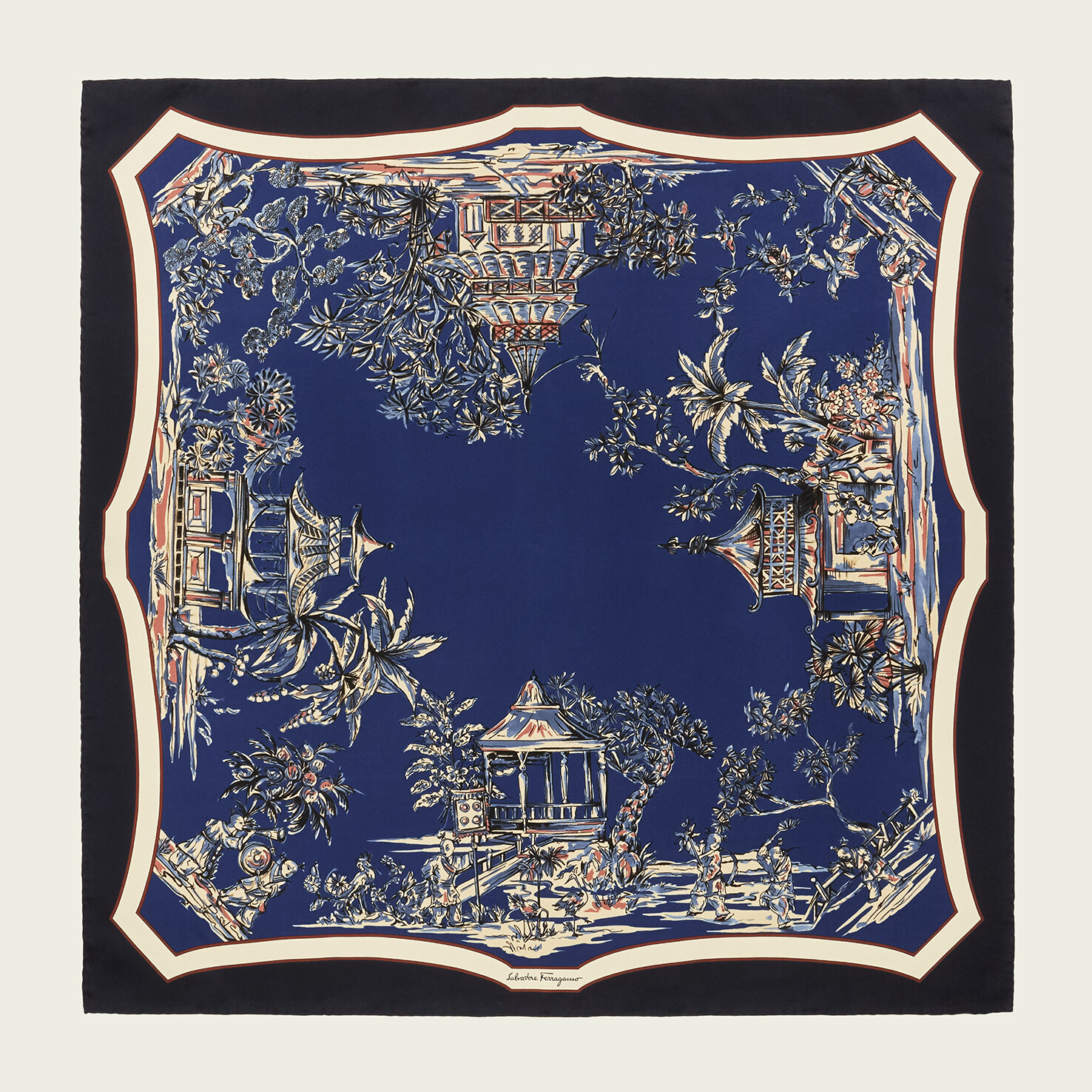

The Como textile industry experimented with square-shaped neckerchiefs, exploiting their frame-like characteristics through the latest developments in printing, drawing on an infinite range of creative and chromatic solutions and establishing valuable partnerships with top names in fashion and accessories.

This exhibition shares the story of this perfect union between creative intuition and high-end industrial craftsmanship—that is, the story behind manufacturing a scarf—through the example of the Salvatore Ferragamo maison, for which silk-printing is the very image of its style.

Until 1960, the name Ferragamo was synonymous with women’s footwear, even if company founder Salvatore always had the idea on his mind to create a fashion house that dressed women from toe to head. In the early 1970s, one of his daughters, Fulvia, created the first in a long line of silk accessories for women and men, characterized by personalized and exclusive designs that were manufactured in Como by Ravasi, Butti e Ostinelli, Ghioldi, Canepa, Ratti and Mantero, which were specially selected depending on the printing specialty required for each run.

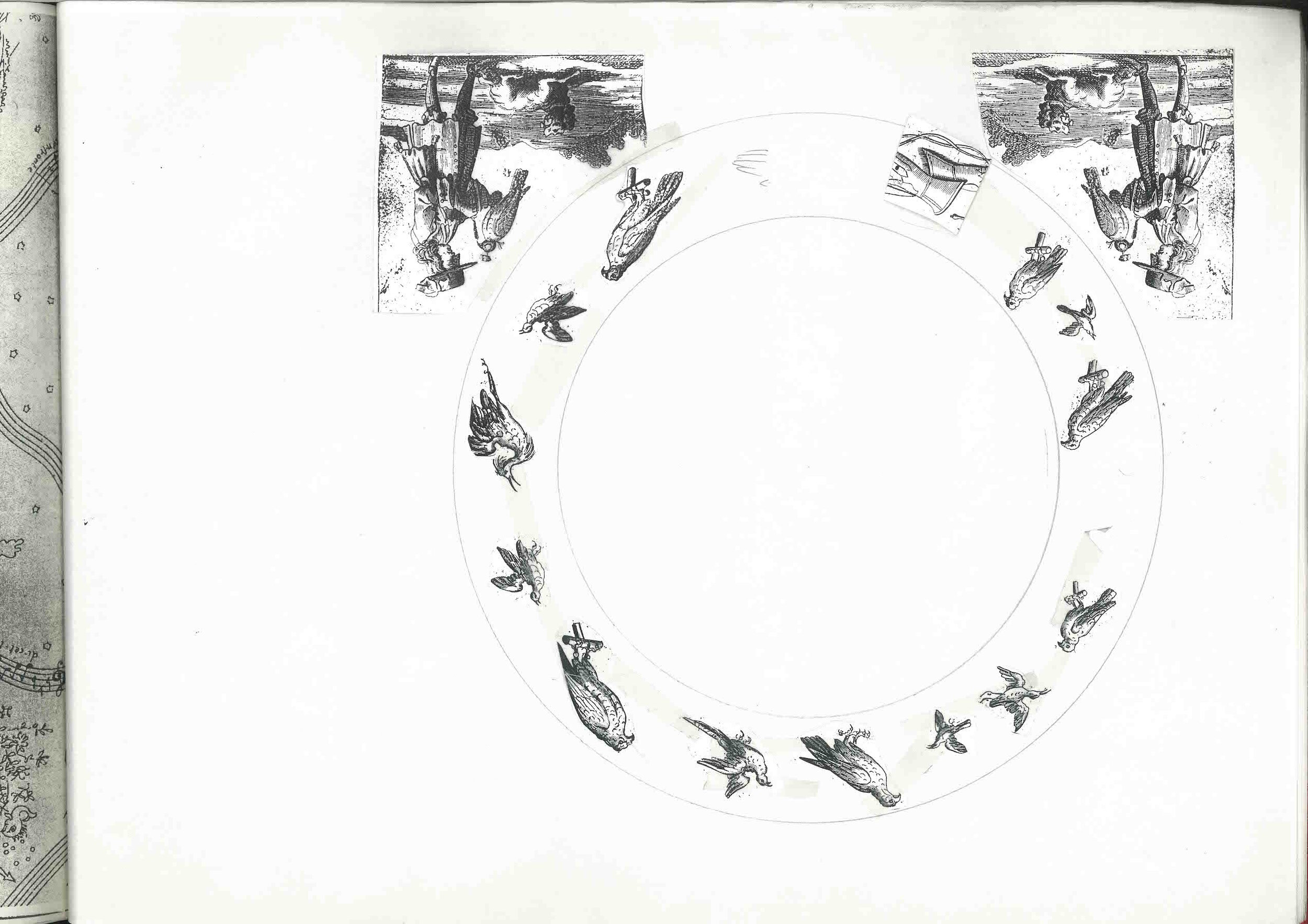

In the early 1960s, silk scarves, were still being bought in from outside companies. The one exception was a scarf produced in 1961 to a Ferragamo commission, designed by artist Alvaro Monnini. The initial idea for this scarf, which ended up being made by Ravasi, was probably Salvatore Ferragamo’s: the ironic and playful streak that pervades the subject reflects his style, which included unusual details in the footwear. The inspiration came from an eighteenth-century engraving by Giuseppe Zocchi in Piazza Santa Trinita, but rather than the real-life stones out of which the austere Palazzo Spini Feroni, headquarters of the Ferragamo company, was made, on the scarf it is built out of stone-shaped wooden shoes; the windows are lined with shoes; instead of birds in the sky, winged high-heeled shoes fly on high; in the square, carriages are made out of elegant shoes, pulled by horses made out of the components of shoe uppers before being sewn together. The edges portray the shoemaker’s tools. The unique nature of this scarf compared with Ferragamo’s output leads us to believe it was more of a promotional item for the company than a product for sale.

Wanda Ferragamo was personally responsible for choosing the scarves that would go on sale. Ferragamo’s regular supplier was Fiorio, a Milanese accessory manufacturer, which every season offered a selection of its designs, often not exclusively. In the early 1970s, after marrying lawyer Giuseppe Visconti, Fulvia, the fourth of the six children of Salvatore and Wanda Ferragamo, who lived in Milan, and enjoyed accompanying her mother on her increasingly frequent visits.

It did not take long for Fulvia to come up with the idea that the time was ripe for Ferragamo to produce this accessory on its own, with its own recognizable, customized designs working closely with the silk printing specialized industries which were distributed in the Como area.

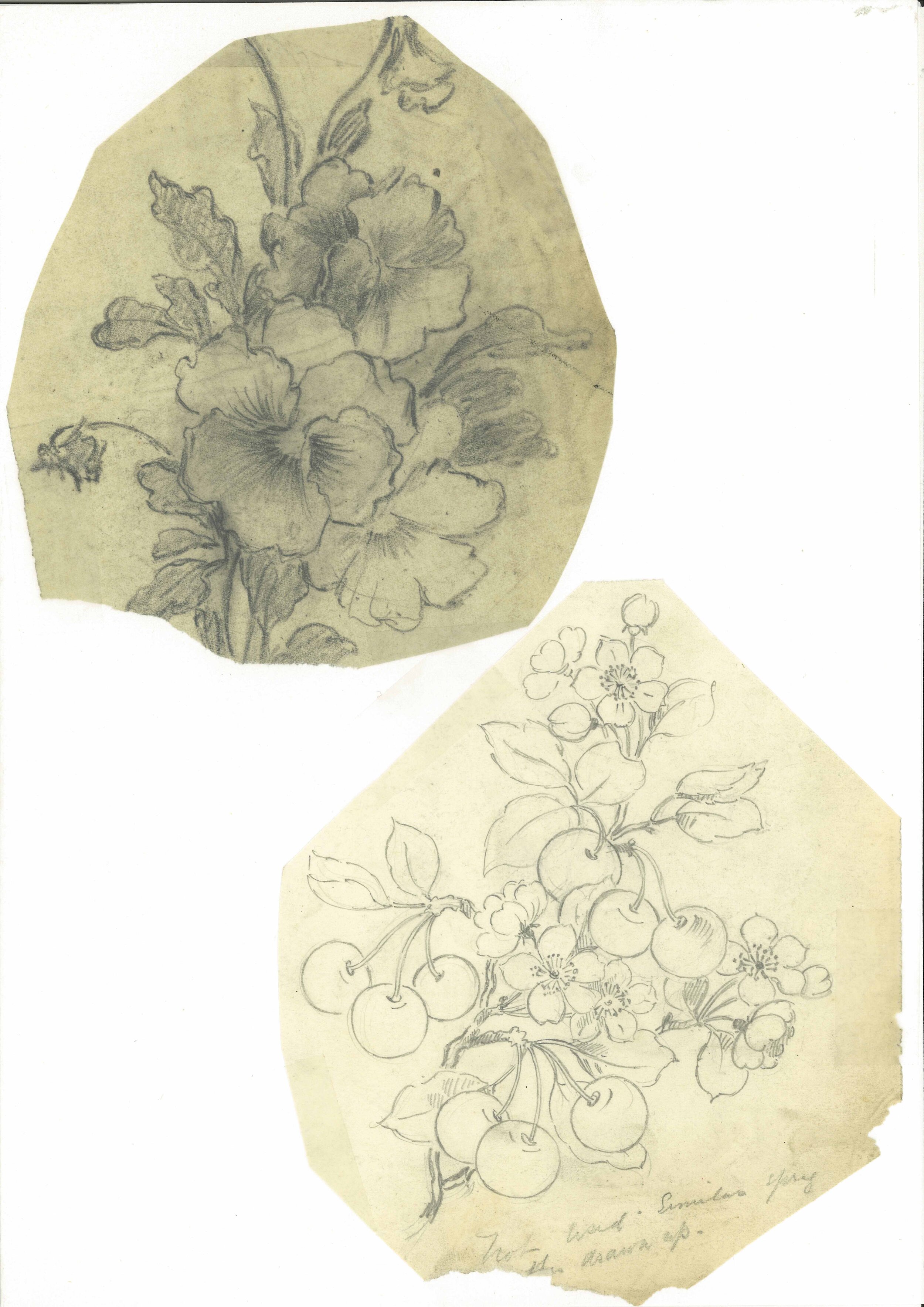

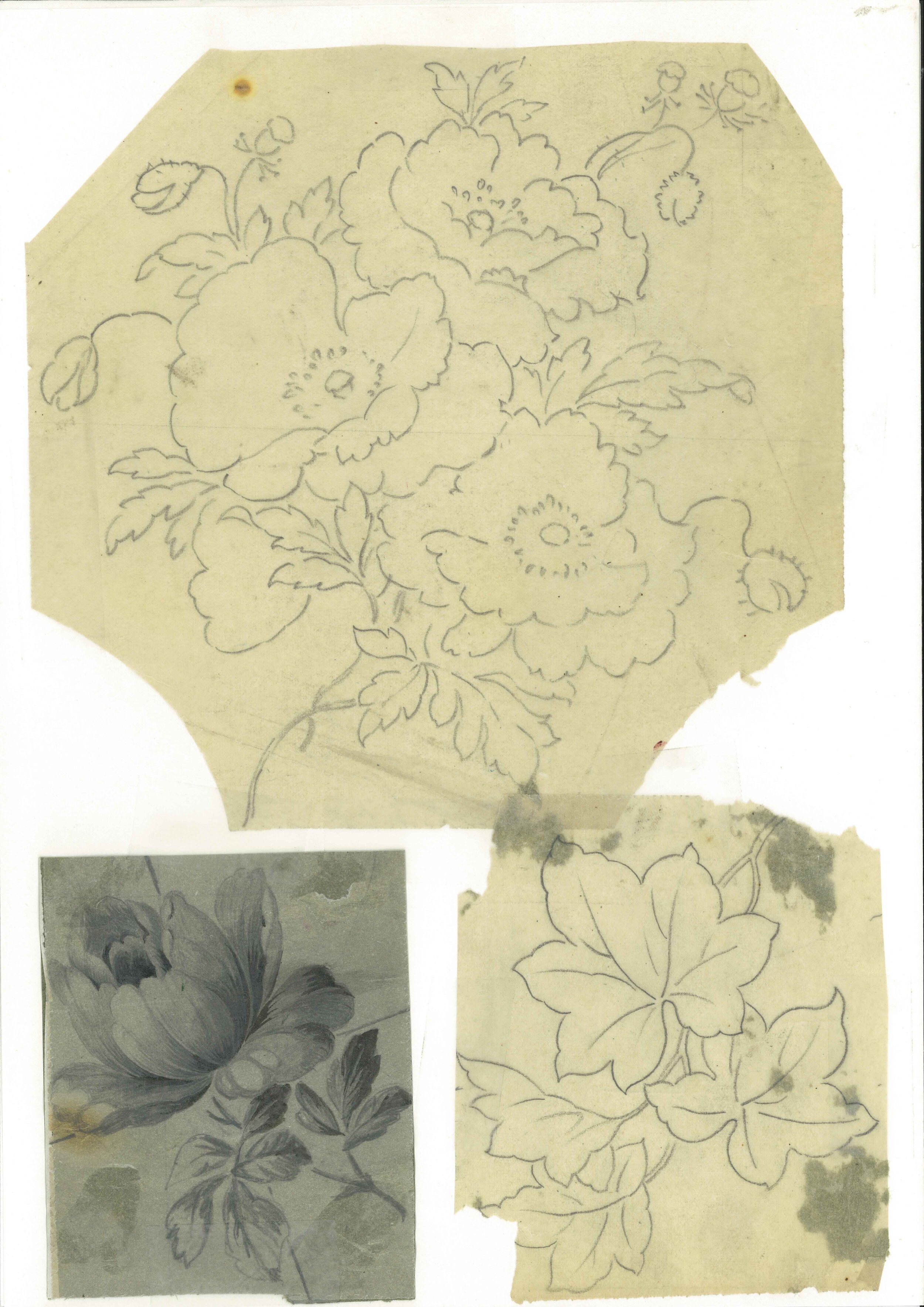

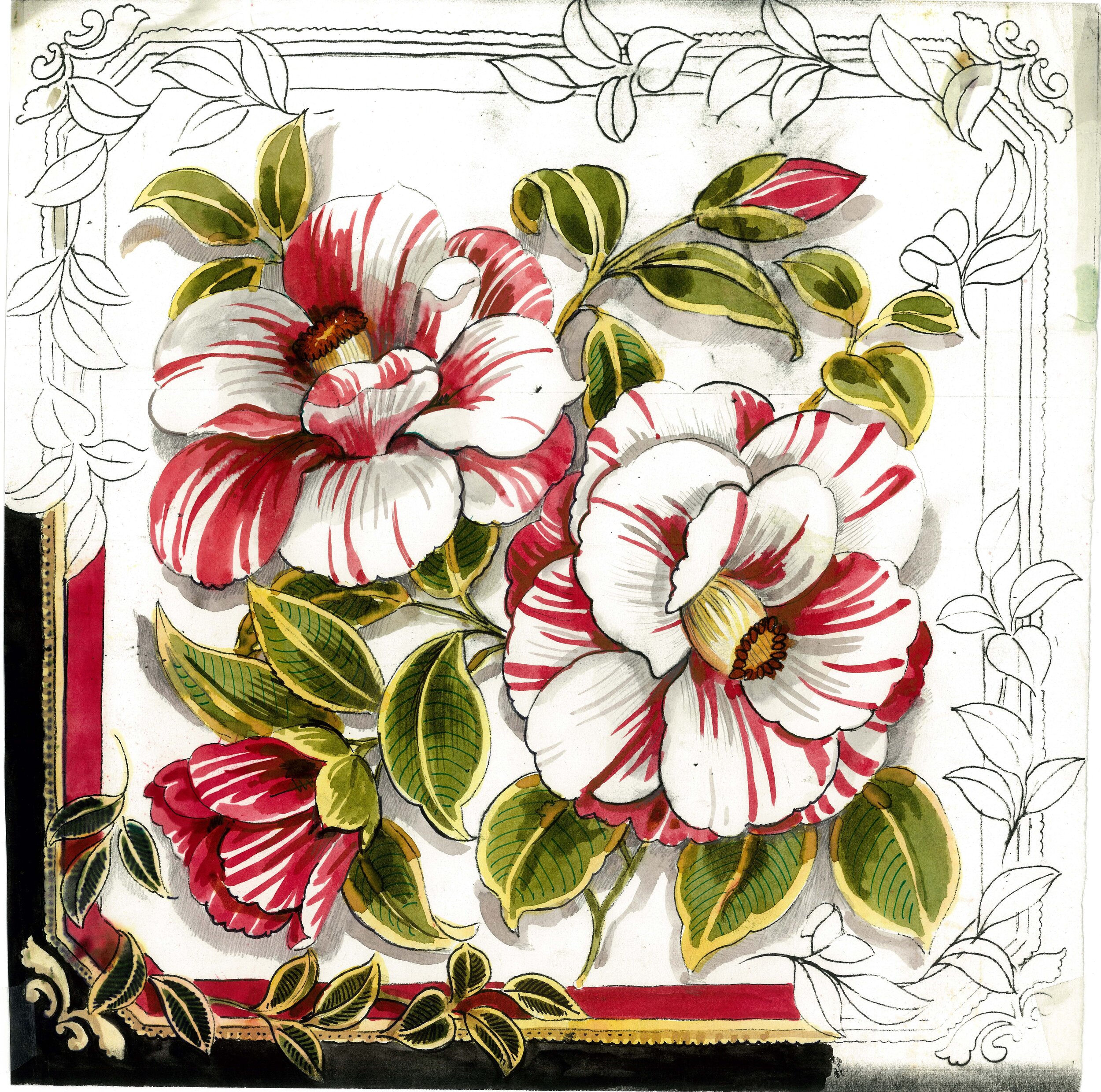

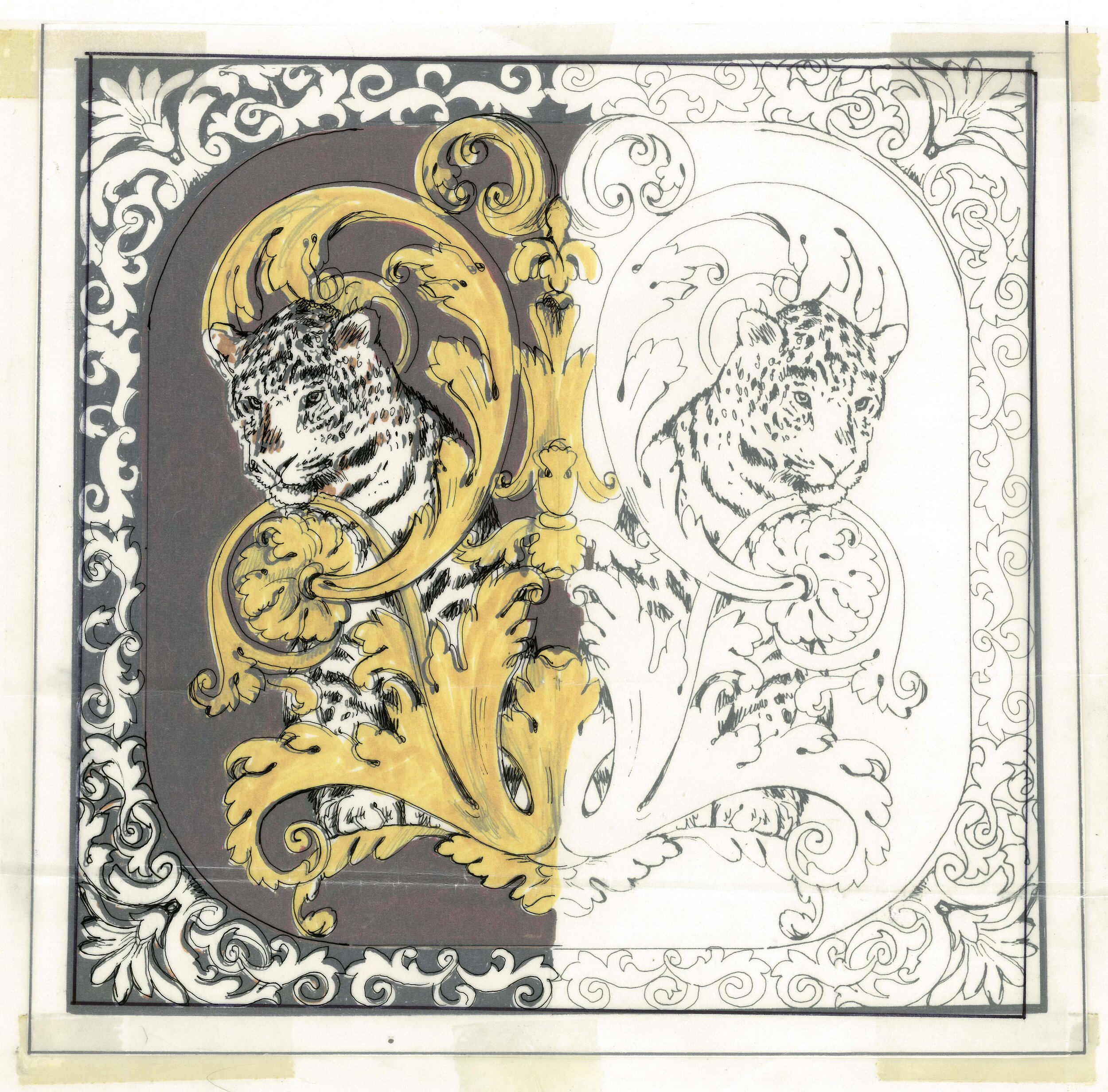

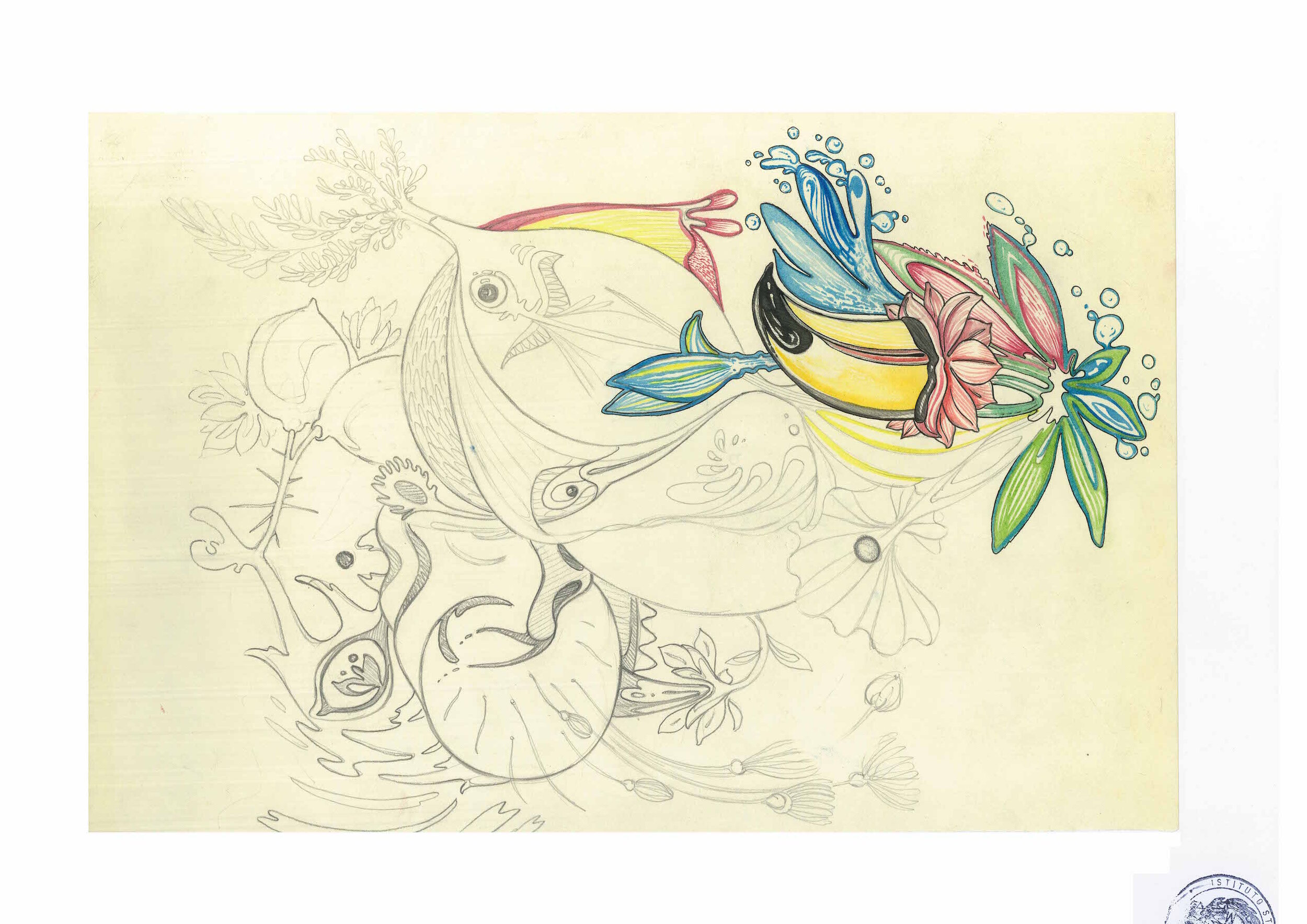

The process of developing a scarf or printed tie is one of teamwork. Despite the use of technology, it continues to be a laborious and demanding process. In the beginning, were used internal draftsmen at fabric printers. Two years later, the company decided to hire its own professionals and illustrators on contract, as well as using in-house employees to design under Fulvia’s supervision.

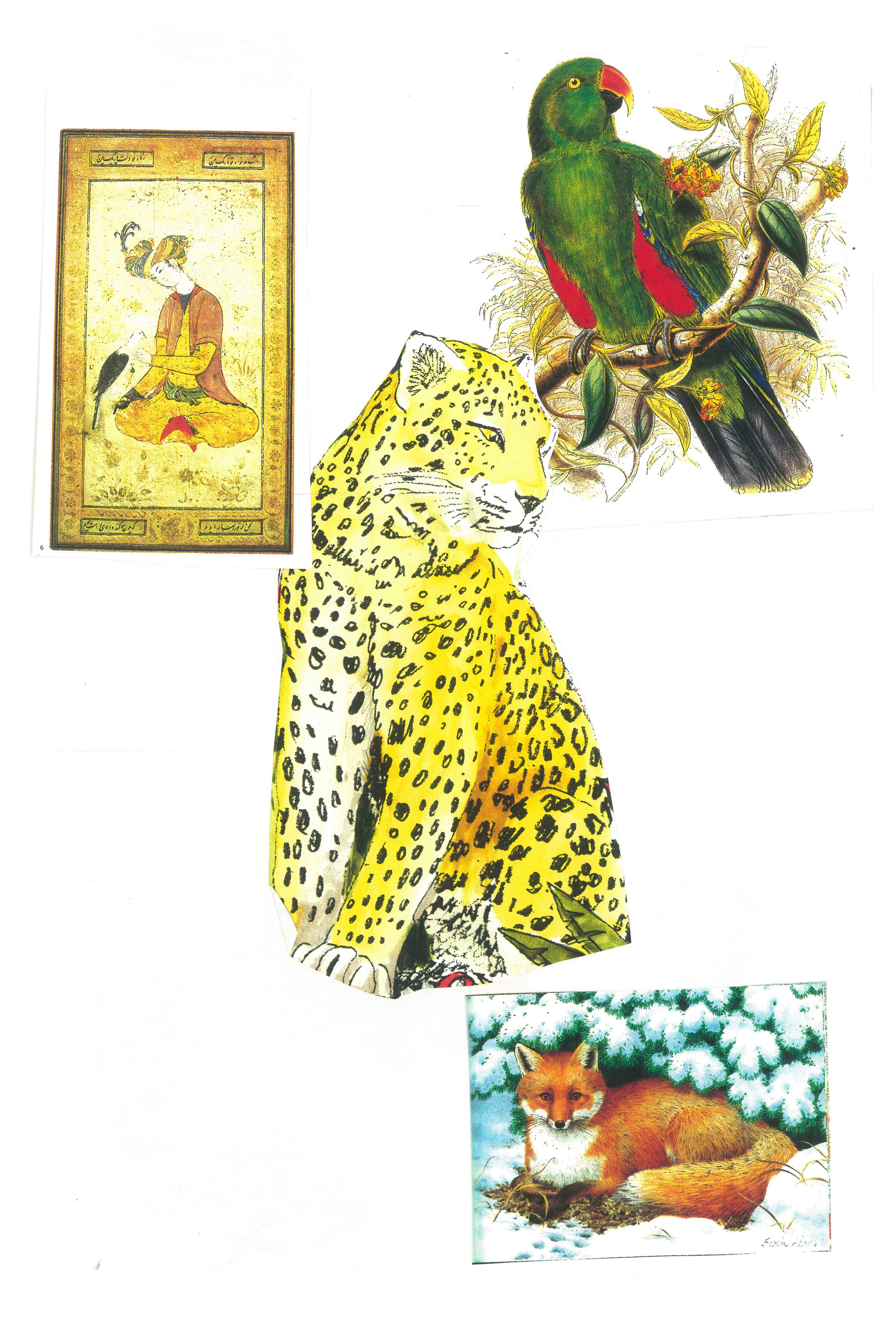

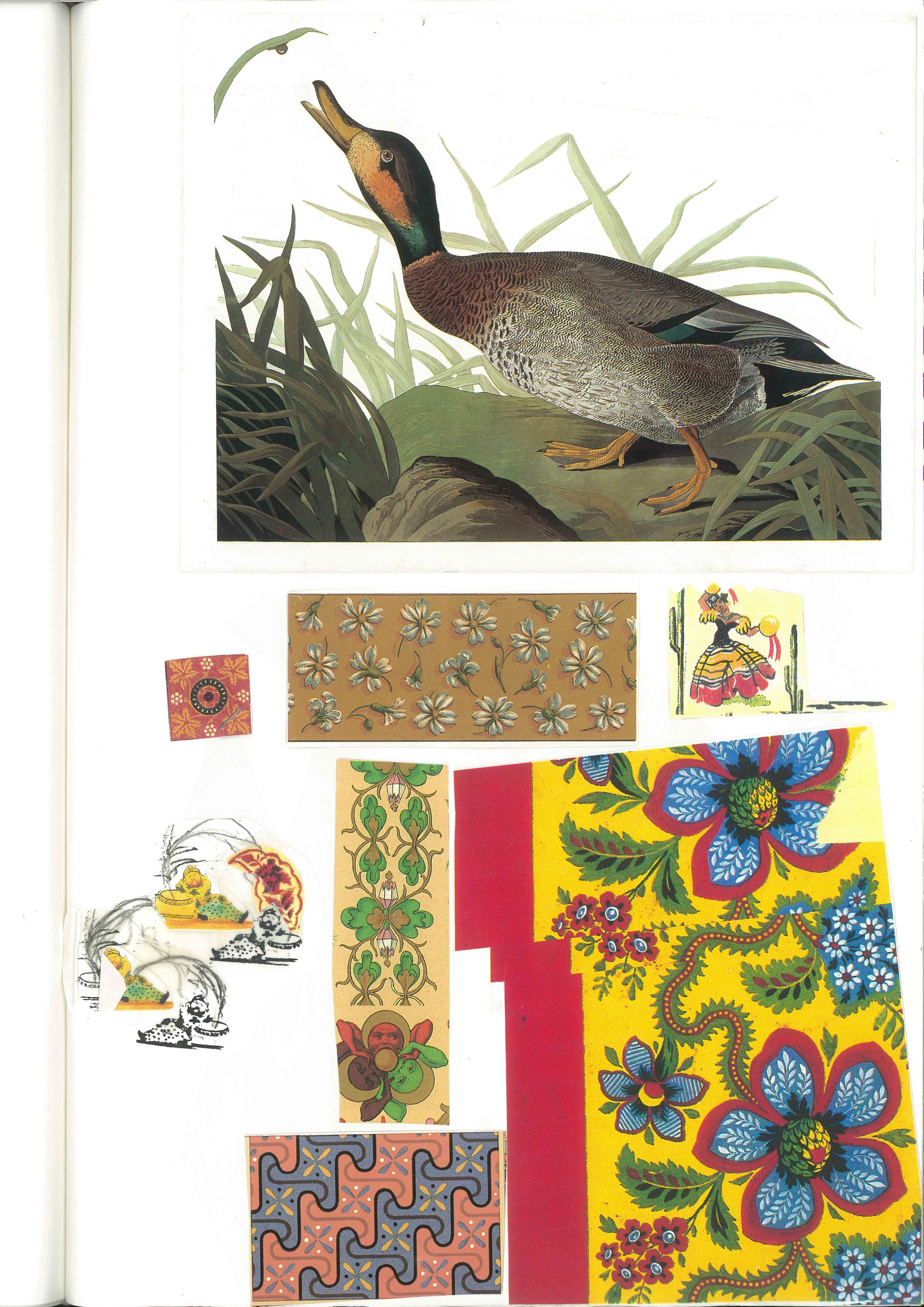

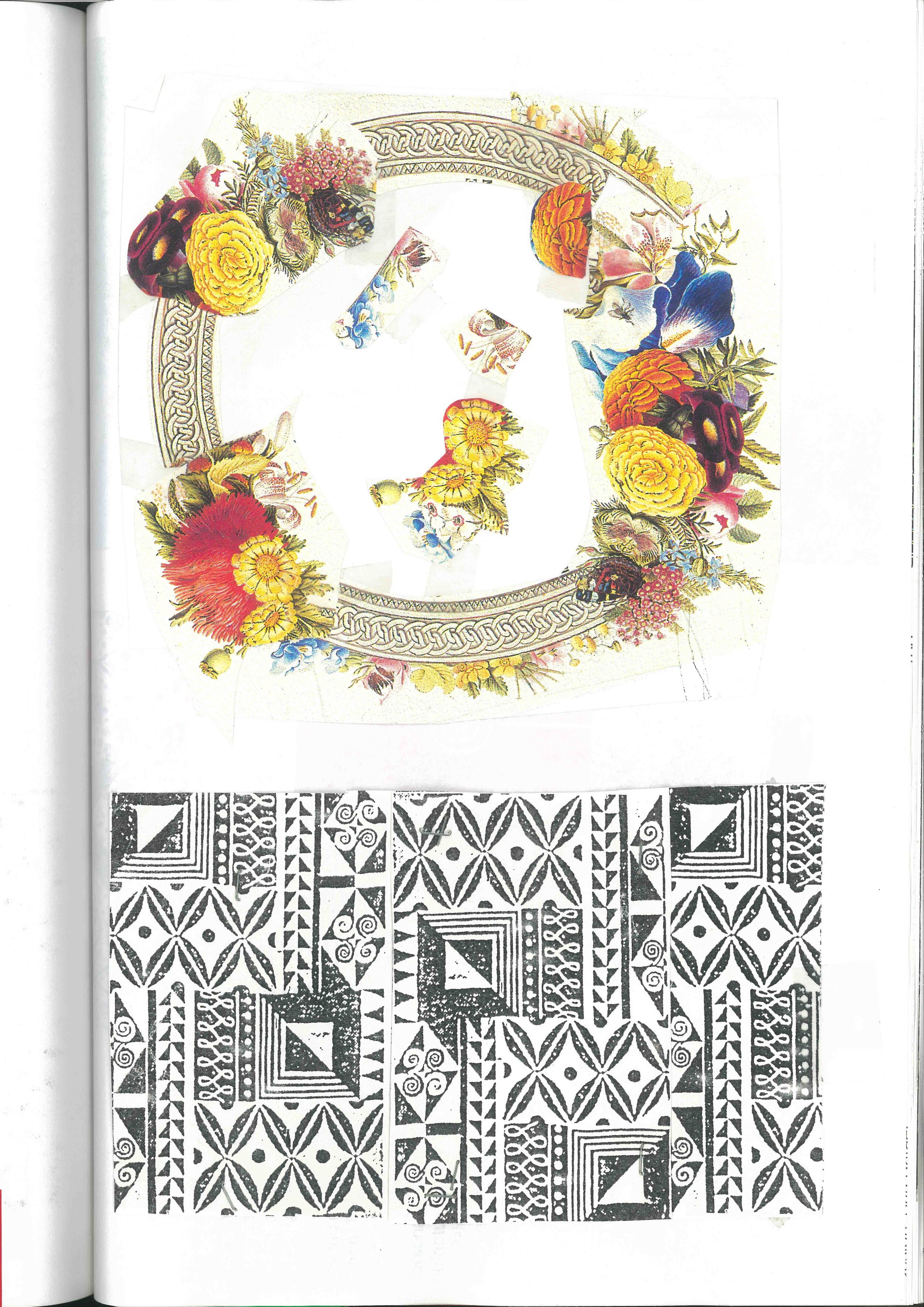

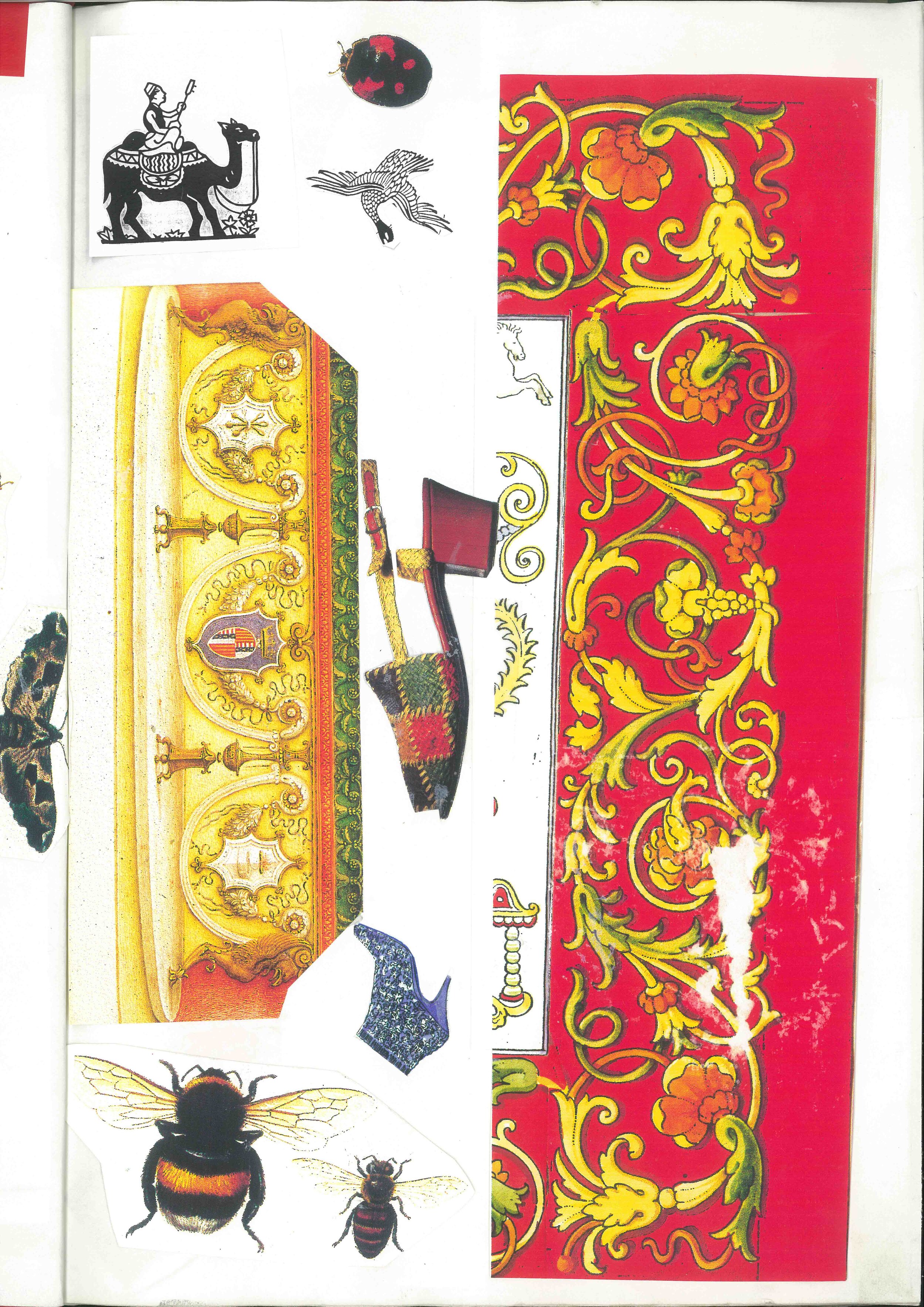

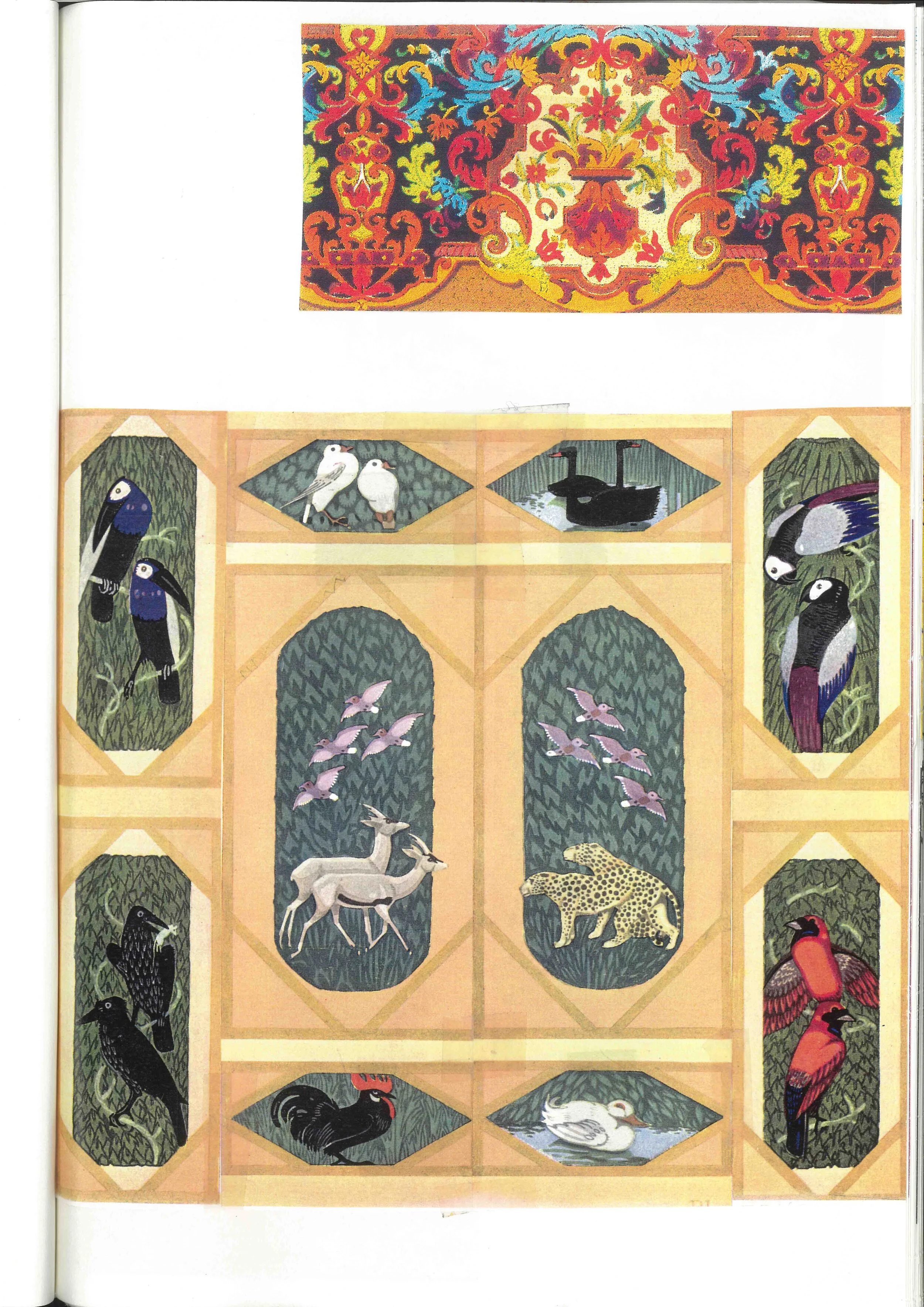

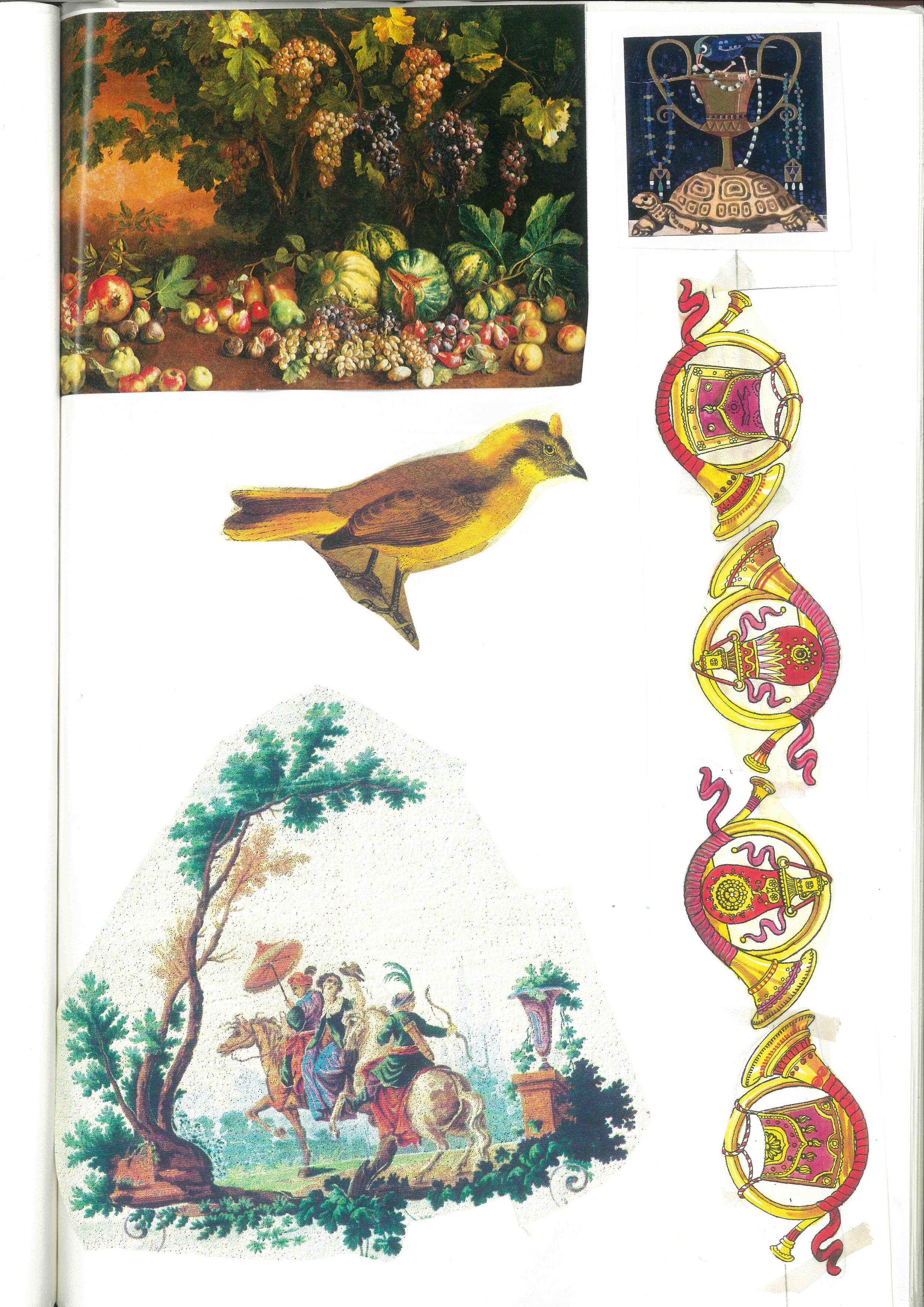

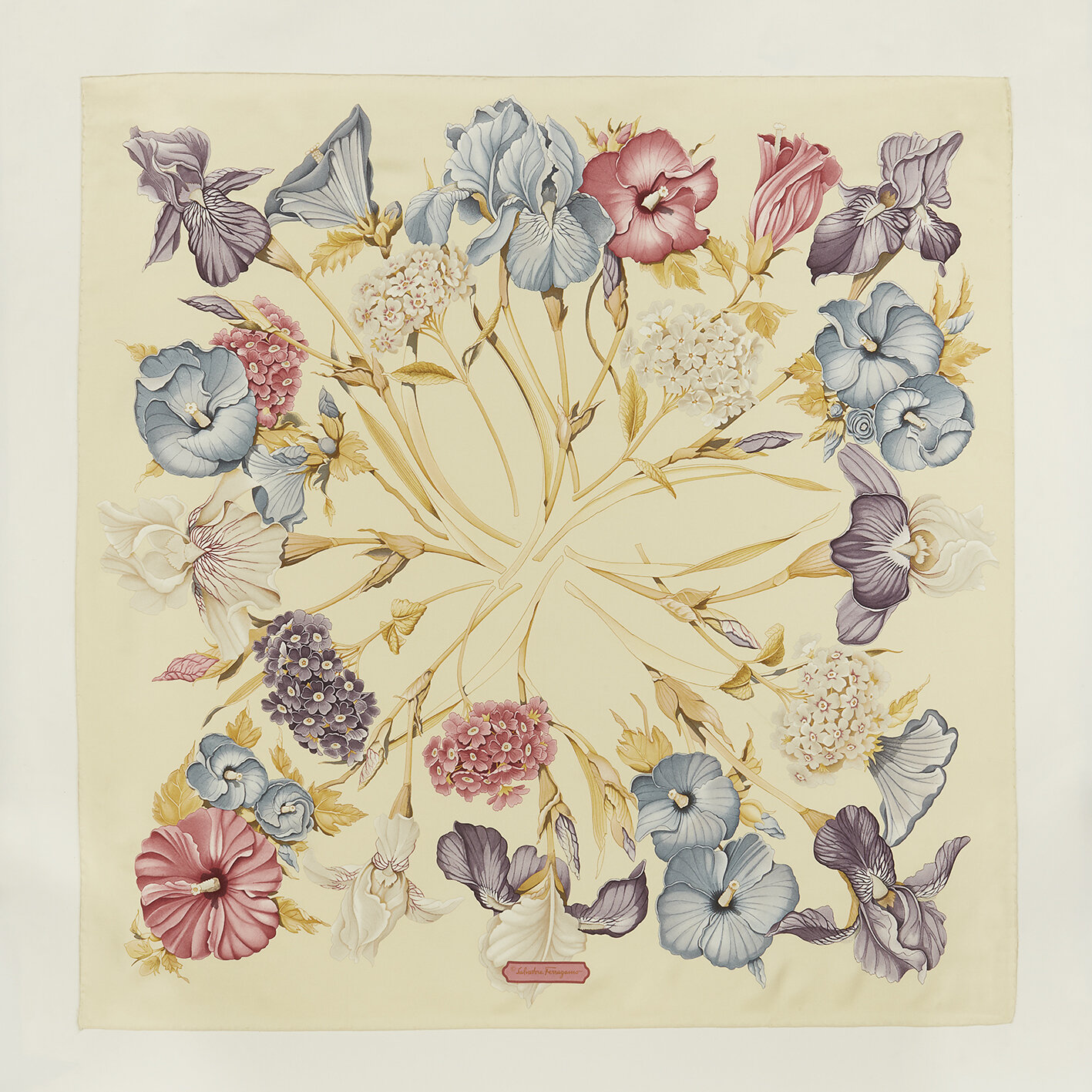

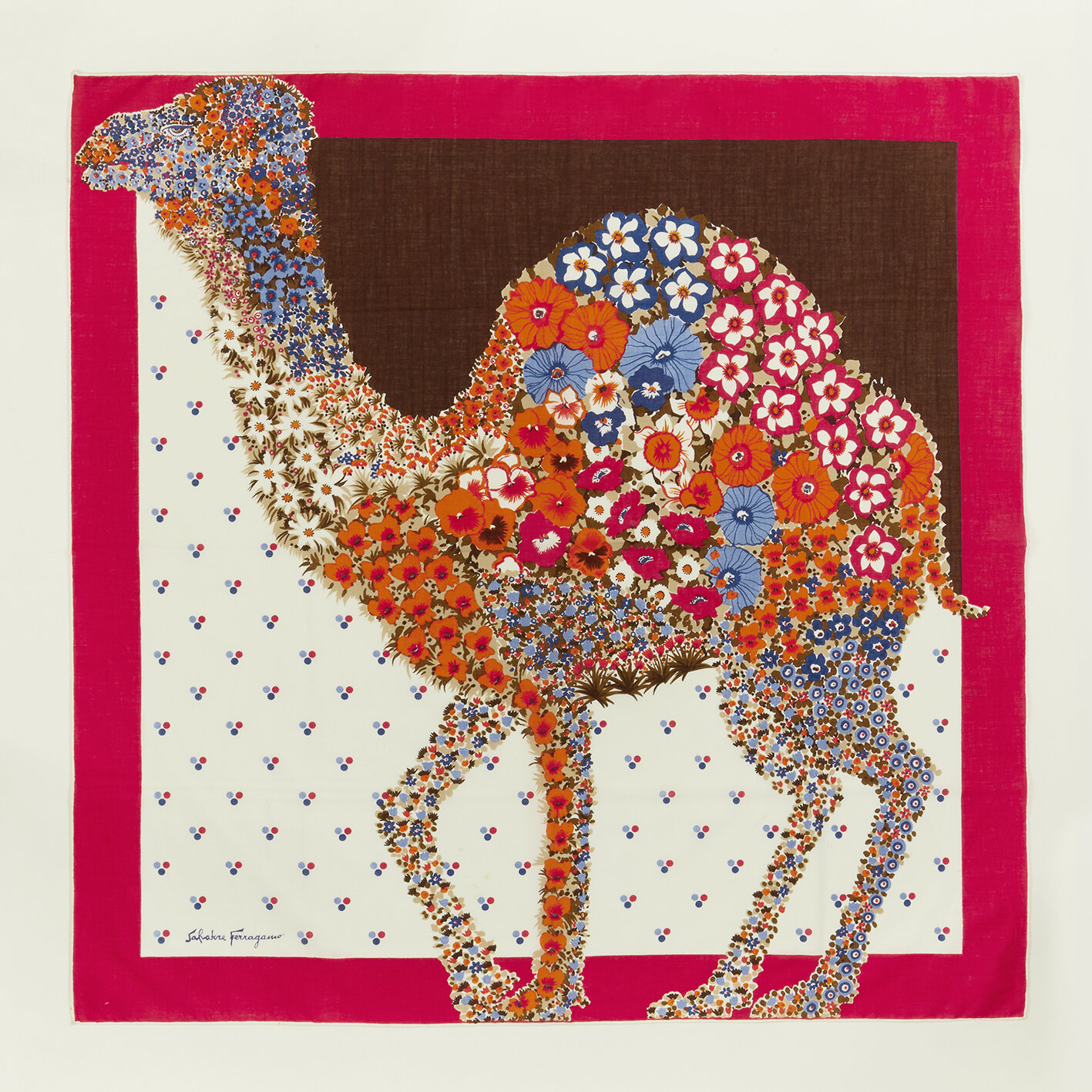

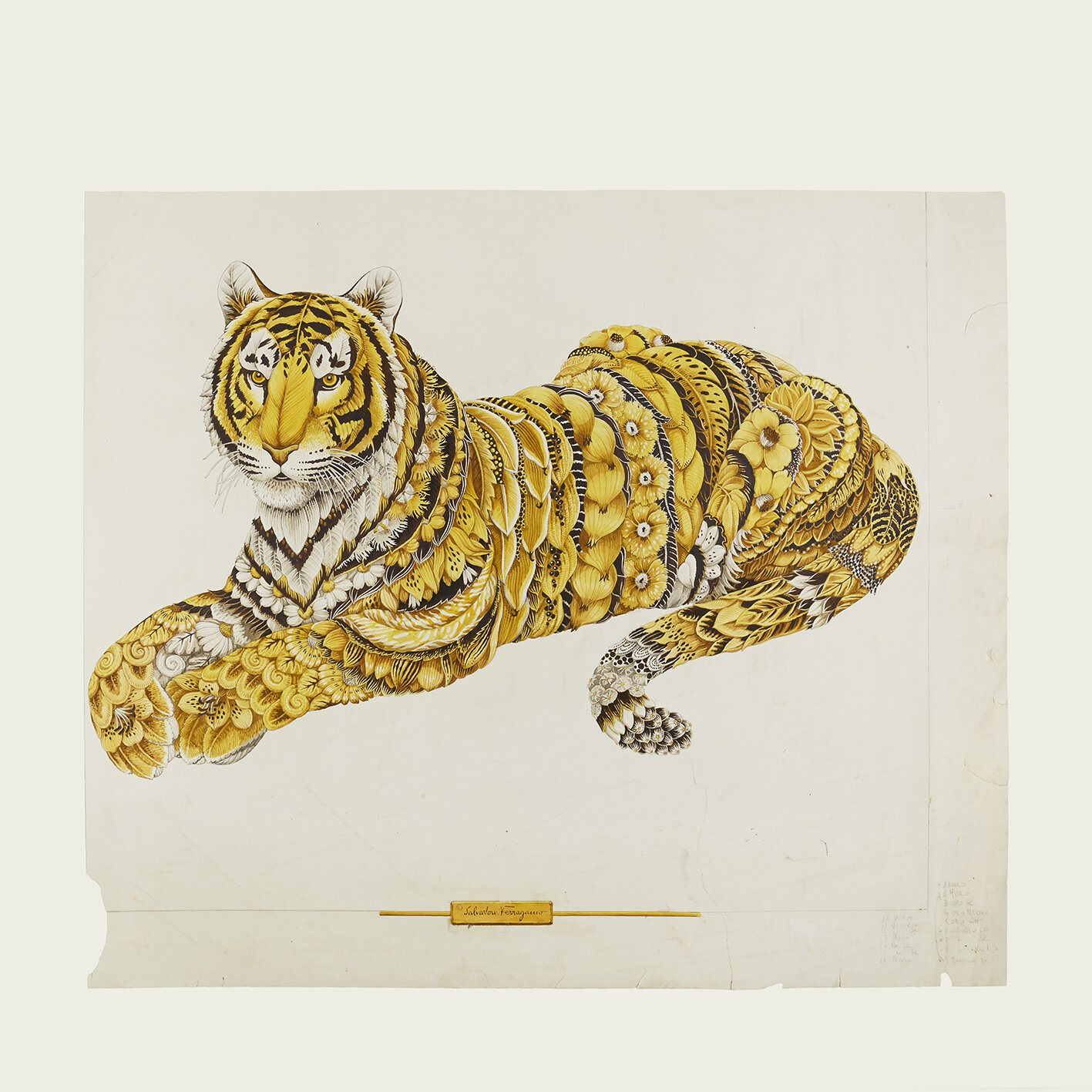

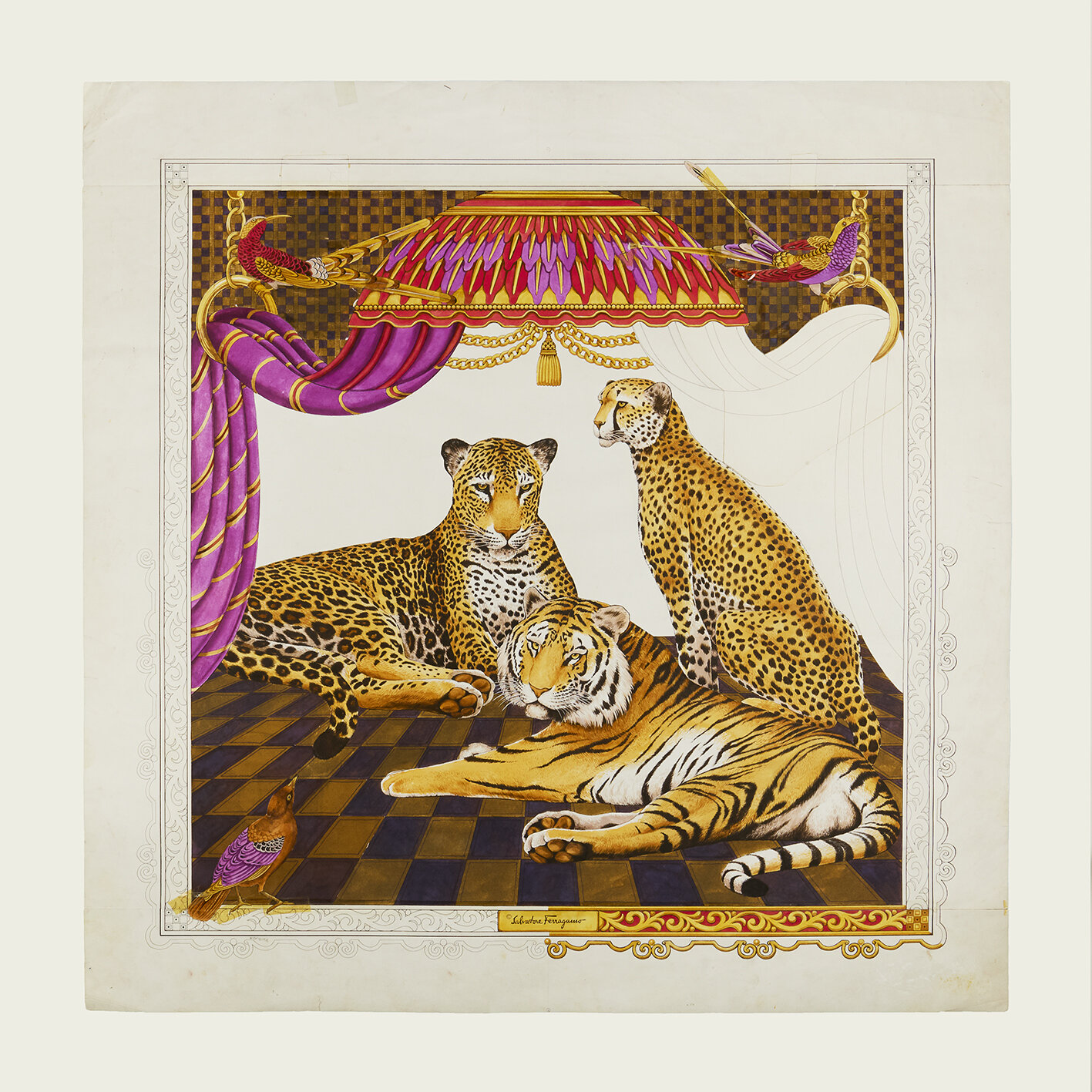

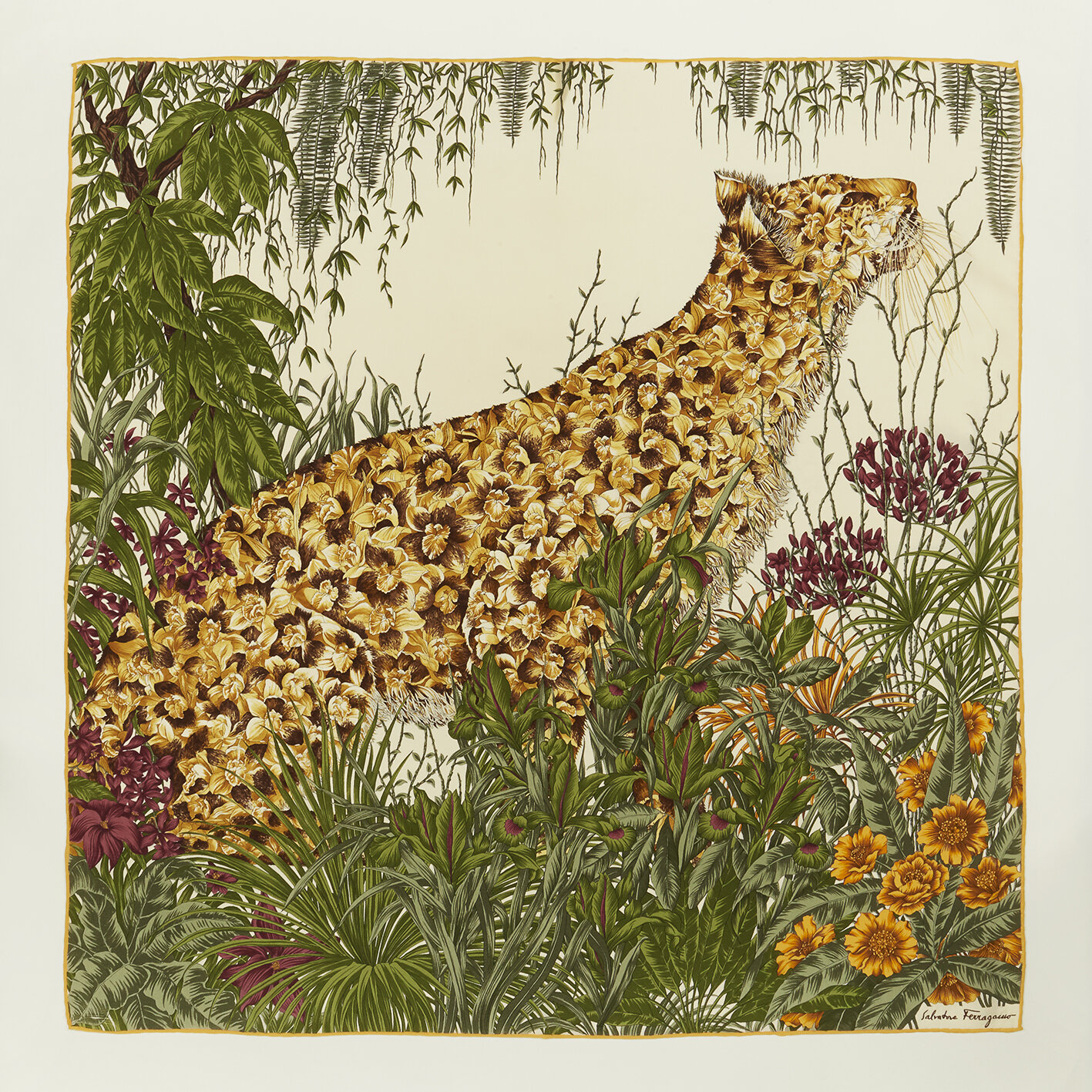

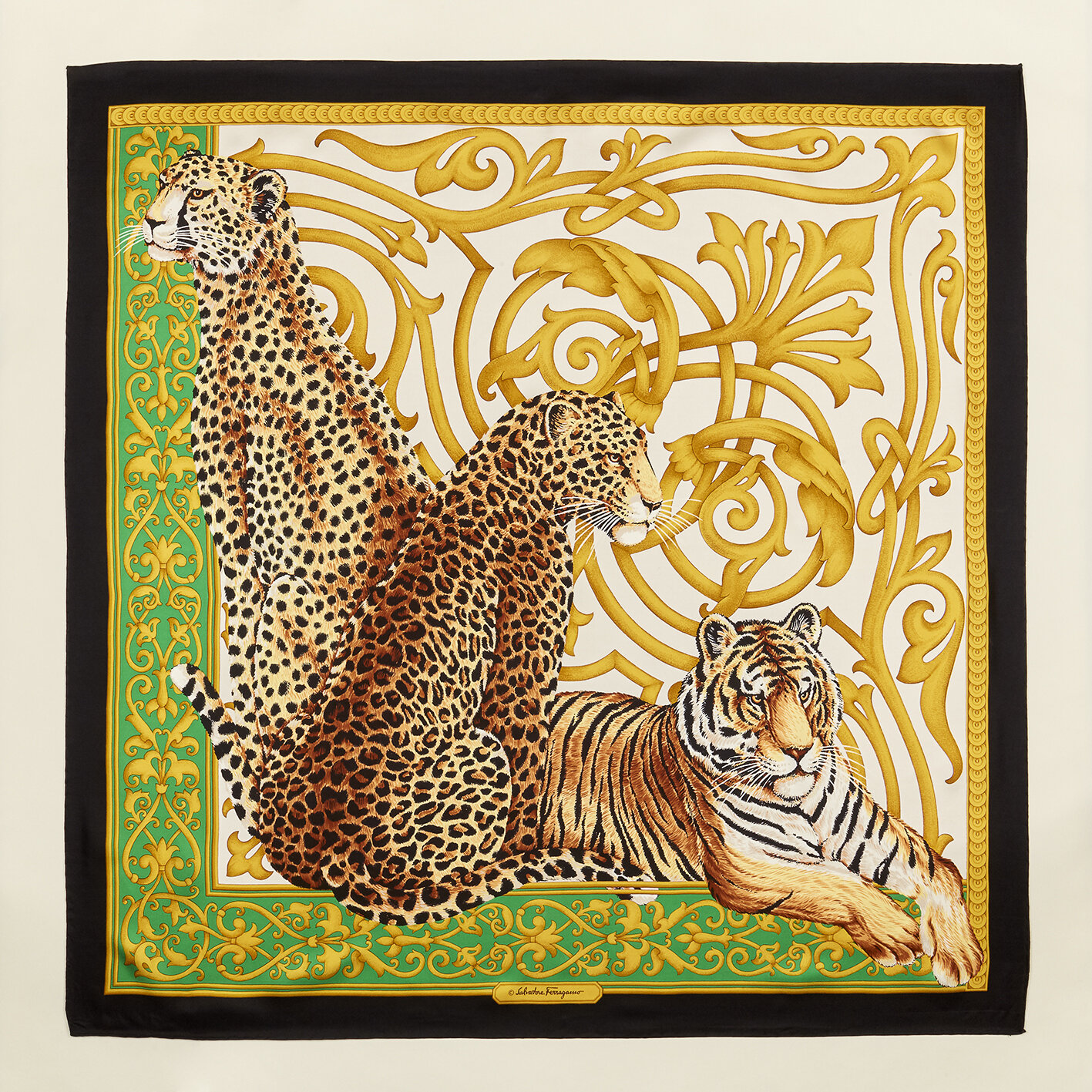

Each designer added his own personal imprint to the scarf. But it was always Fulvia, as creative director of all silk collections for men and women, who “played the first note,” tuned the instruments, gave the creative idea to the designers in charge of developing those initial sketches, which only after her approval and modifications, were created at real size. From the very beginning of her professional career, it was Fulvia who suggested sketches made using a collage technique.Miniature ethnic scenes, cultural themes and popular illustrations became recurrent Ferragamo tie subjects; flowers and the animal world dominated their scarves. In the early years, the two decorative approaches overlapped: the firm’s earliest designs consisted of animals made of a patchwork of flowers. From the late 1980s onwards, floral fantasies proliferated, alongside marine fauna, hunting subjects, footwear created by Salvatore Ferragamo during the early decades of the twentieth century and, above all, exotic themes, dominated by felines prowling through somehow-reassuring jungle scenes.

Created by top illustrators led by Fulvia, this eclectic creative world has been preserved at the company’s historical archive, a veritable Wunderkammer that reveals how the apparent simplicity of these silk prints, intended for worldly use, actually conceals great conceptual and productive complexity.

Fulvia’s untimely death in 2018 left an immense void. However, her passion and ideas live through the people Fulvia trained over the years, who continue to design and produce as if she were still at the helm of each collection and through the archive materials. They allow to today’s designers to re-interprete Fulvia’s classic themes in a contemporary way, as may be seen from recent designs that put forward a new type of patchwork, obtained by vertically staggering two famous print designs from the past, or to re-launch the brand’s most iconic scarves under the Ferragamo's Creations line. This documentary and human heritage keeps the unforgettable Silk Lady and her magic alive.

Designing from Albums

Judith Clark began her work within the Ferragamo archives in 2019 - looking at the extraordinary albums held in the silk department in Milan. We have, below, quoted from her catalogue essay which describes her discoveries and how she began to wonder how these might be translated into exhibition-making practice:

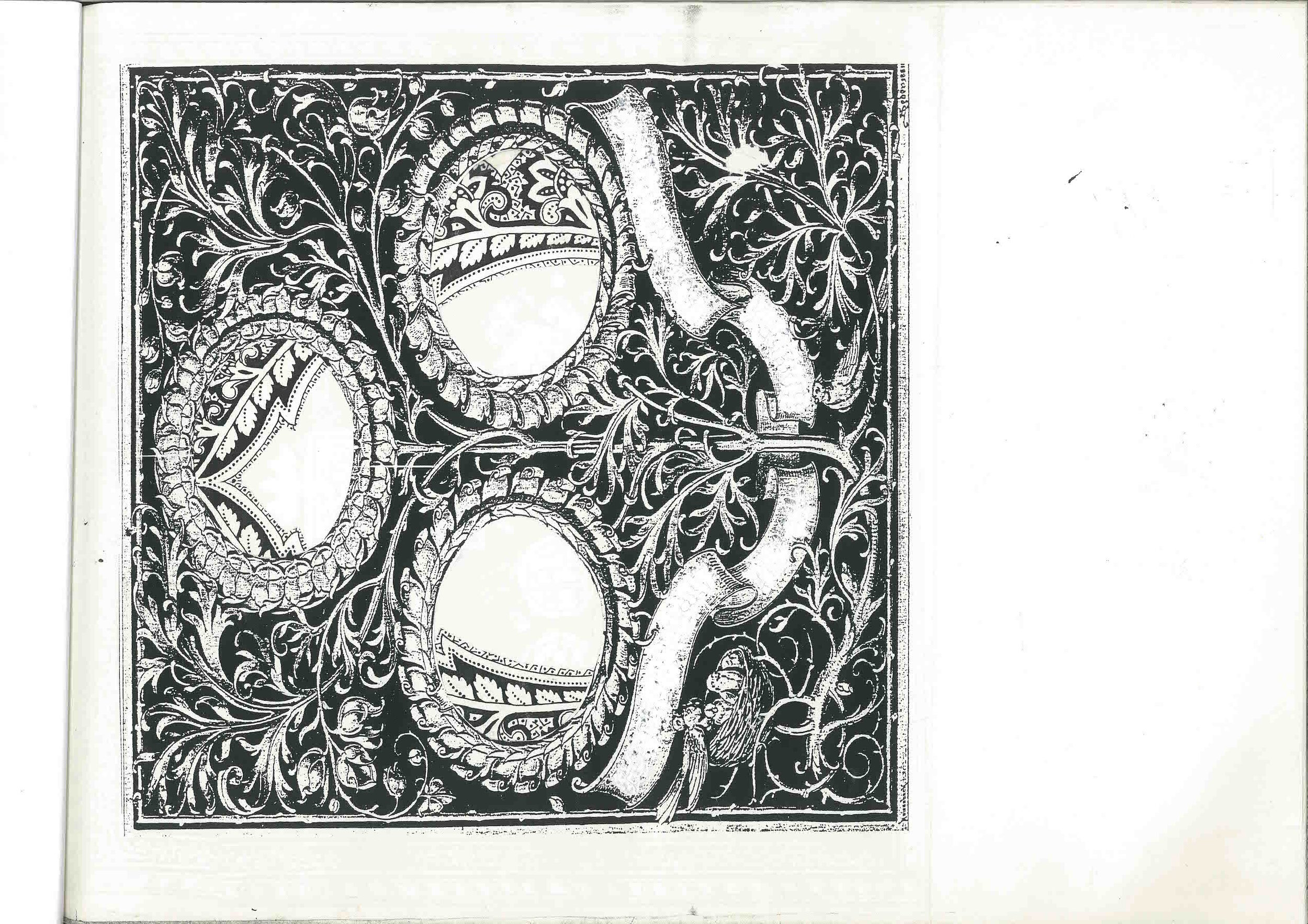

“Cut out visual references without written captions, which were created not for academic research but for more design, for further combinations, are stuck to the pages of the albums both demanding and resisting explanation….

The unplanned pages of the albums have an inevitably fixed (sequential) record of collecting—even though they were never dated, nor intentionally fixed—so we can track the departments’ interests at any given time, like a series of day dreams, but we do not know for certain how often and when they were consulted or actually used, and how often a given motif might have been revisited. For this exhibition, for the first time, the references have been so methodically tracked by the Museo Salvatore Ferragamo staff and paired with designs that went into production.

What the exhibition introduces is the idea that the collecting has already been done, reflected on the fine silk scarves—the bringing together that is usually the task of the curator, reflecting Fulvia Ferragamo’s view. The task was therefore to show the moment of translation in a way that did not return the objects to too earnest a museum project, but use it as inspiration.

The albums have been predominantly used for (historically) gendered design: (largely women’s) foulards and (men’s) ties. The essential 90 x 90 cm template for the former, into which the references have been so imaginatively entwined, overlapped or arranged to respect their four sides—we need to remember the square format provides no hierarchy of perspective; and for ties, it has been about shrinking the design down to fit its tight vertical dimensions.

The exhibition borrows from these ideas: how to stack motifs; how to give a corner emphasis; it asks whether the frame becomes as important as the ‘object/reference’; how these might be built up; what then might be an interesting way to show the moment 3D becomes 2D (and vice versa); how might the design use a repeating pattern; is that why so many of the floral references in the albums come from designs for wallpapers—because they were already fit for repetition?

I also love the perimeters of the paper fragments pasted into the albums that we, the viewers, always assume reveal the carelessness of the scissor’s cut—or reflect the way in which we rationalize the edges of something we are cutting out, or how an unskilled child might cut something out. I think those spaces are sometimes the most interesting, leaving open the idea of an original context being transposed, and how much to bring with the central depicted object, or what that might be? It makes us ask where images are from.

The exhibition performs this regress in its cabinets, the scarves inhabit the present, they hang on the gallery walls, and remain the focal point of study, whilst a game is played within the walls - embedding fragments from other museums or, a section of a room from which an object has been borrowed for example, reminding us of the irregular cut-outs in the albums.”

THE EXHIBITION

Section 1

Sun Yuan & Peng Yu and the Silk Road Chimeras

(from the essay of Demetrio Paparoni in the catalog Silk, Electa, Milan 2021)

The first exhibition room hosts Sun Yuan & Peng Yu’s installation which brings together some of the animal sculptures that the artists used in their previous installations If I died and I Didn’t Notice What I am Doing and taxidermy from the Naturaliter, Capannoli (Pisa) and the Museo di Storia Naturale (La Specola), of Florence, one of the most prestigious zoological collections in the world, which exhibits naturalized specimen of recent acquisition and ancient preparation, donated by the Grand Duke Peter Leopold of Lorraine in the late eighteenth century .

Sun Yuan & Peng Yu are accustomed to taking apart and reassembling existing layouts to create brand new arrangements. For the exhibition at Museo Salvatore Ferragamo they have created a design for a silk scarf. Both the art installation and the pictorial work, conceived to be reproduced on silk twill, conceptually epitomize how the Silk Road has long been a fertile route for encounters and exchange between Orient and Occident.

For centuries, the villages and towns along the Silk Road have welcomed travelers and merchants, its caravanserais and monasteries providing shelter for man and beast, making it possible for outbound and homebound travelers to carry with them not only valuable artefacts, spices, handicrafts, and art, but also technical and scientific knowledge, philosophical and religious concepts, and folk tales.

The wallpaper in the room reproduces a map of the ancient route, locations highlighted with figures, buildings or animals taken from the prints created by Fulvia Ferragamo, who was fascinated by exoticism from her earliest years. The starring role in this room is played by Sun Yuan & Peng Yu’s artwork. In the two contemporary artists’ personal vision, the Silk Road is a spiritual path, a search for the self via an encounter with the other. Their vision embraces the idea that in antiquity, traits that were common to various cultures connoted cosmological and religious conceptions symbolically, mythologically, and indeed visually. The two Chinese artists assume that it was specifically the fascination of these myths that encouraged contact between far-off peoples.

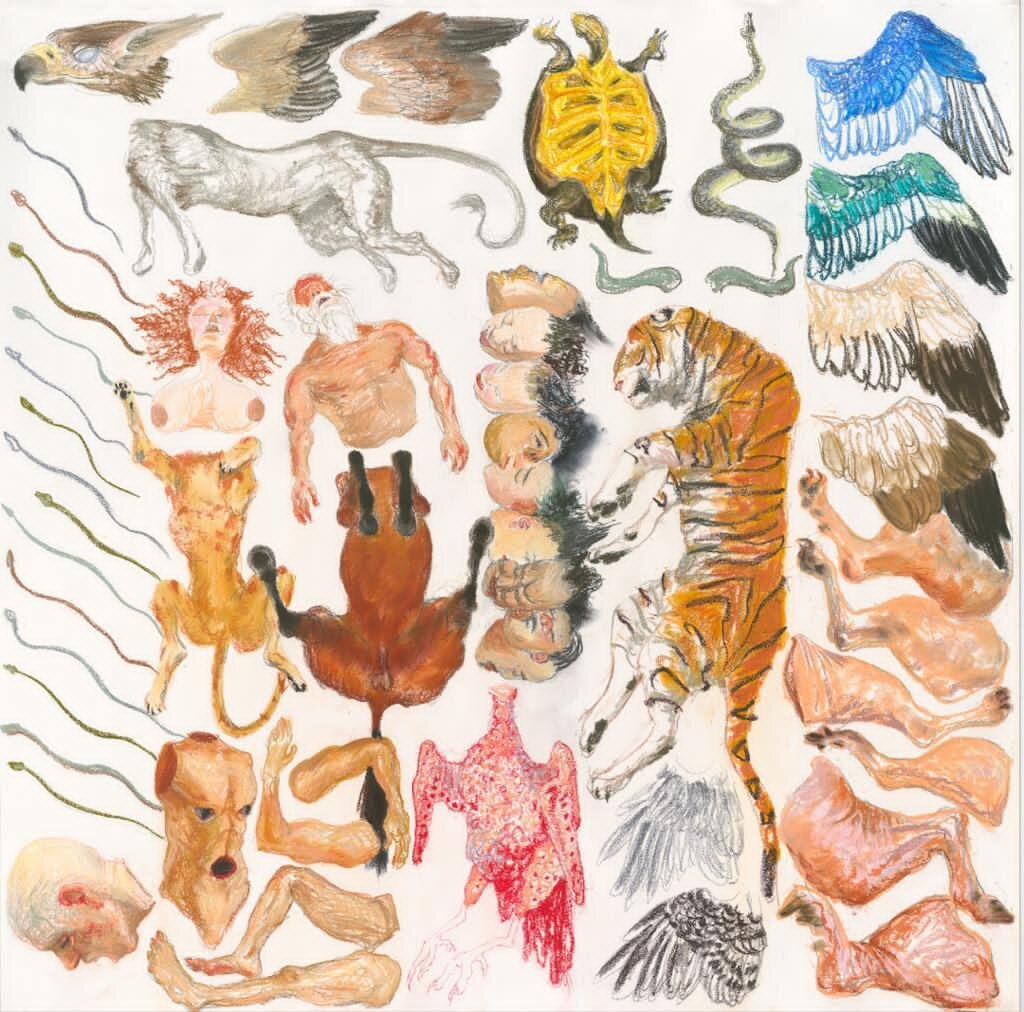

The figuration of the scarf that Sun Yuan & Peng Yu have created highlights the process of hybridization triggered by the exchange of narratives among people who have traveled or lived along the Silk Road. The artists adopted here an anthropological approach, breaking down figures from Chinese and Western mythology and re-organizing them into a sort of visual archive in which we recognize: the snakes forming Medusa’s hair, while she is portrayed with a bald head; the beak, the wings, lion’s body and snake’s tail that characterize the griffin; the turtle and the snake that, by intertwining, create the Black Warrior, one of the symbols of Chinese constellations (better known in the West as the Black Turtle); the woman’s bust and lion’s body that make up the sphinx; the man’s bust, horse’s body and bow of the centaur; the trunk and the limbs of Xingtian, who in the ancient Classic of Mountains and Seas was beheaded for daring to challenge the Yellow Emperor of China, only for his nipples to transform into eyes and his navel to become a mouth, allowing him to fight on; the body of an eagle and nine human heads that symbolize the immortality of a particular Chinese phoenix; the tiger’s body, buffalo’s horns and wings from the Qiongqi bird, the evil demon devourer of men in Chinese mythology; finally, the six legs and four wings that distinguish the primordial chaos of Chinese cosmogony. Animals, which first appeared in Paleolithic cave paintings, have always had a supporting role in man’s cognitive experience. Long associated with magical and religious visions, these hybrid mythological figures combine human characteristics with traits from different animal species. However, these imaginary figures incorporating animal parts always draw on reality and the visible: the dragon, a recurrent figure in Chinese mythology, is a snake with the head of a crocodile, the whiskers of a catfish, the mane of a deer and the legs of a bird. Similarly, the siren, which recurs in Greek mythology, is a figure with the face and torso of a woman and wings and legs of a bird. Thus, in both East and West, animals have always played an important role in our mythological imagination.

Regardless of home culture or geographical area, it is as if man had nourished his imagination by drawing on a common reservoir of visual information. From this viewpoint, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu’s fantastical animals perpetuate an approach that basically has long been a unifying trait in human behavior. Furthermore, they remark that if each part of an animal expresses a prerogative symbolizing a power of the mythological figure whose whole is derived from all these parts, the common animal possesses that power too.

In Were creatures born celestial?, rather than creating hybrid mythological figures, Sun Yuan & Peng Yu offer up their parts as a sort of sampler, allowing us to recompose them and create our new hybrid figures. This may seem quite distant from the subject matter the two artists have previously focused on, for the most part to do with observing man’s psychological reactions in societies undergoing profound transformations, both in terms of individual relationships and the geopolitical scenario. So, what prompts Sun Yuan & Peng Yu to address myth-related issues at a time in history when the common ground on which East and West meet (and clash) is focused on scientific research (and competition)? The answer may be found in the very nature of myth: Were creatures born celestial? reminds us that myths nourish and revitalize an imaginative and narrative plane that today is relegated to the sphere of video games and science fiction, conveyed through the internet into our infosphere. By referencing myth-related themes, they respond to the (conscious and unconscious) need many people feel to reconnect modern-day man with that original substrate, one that has survived the changing times and evolution down the ages.

Drawing for the scarf

Were creatures born celestial?

Description of images

1 - Medusa

2 - Griffin

3 - Centaur

4 - Xing Tian (Corporal punishment)

5 - Xuan Wu (Black Warrior of the North)

6 - Jiutouniao (Nine-headed phoenix)

7 - Qiong qi

8 - Hundun (Chaos mythical)

1. Medusa

Medusa, also called Gorgo, is one of the three monstrous Gorgons of Greek mythology, who are generally described as winged human females with living venomous snakes in place of hair. It is in the Roman poet Ovid’s Metamorphoses that Medusa’s story is most deeply elaborated. According to the poem, she was very lovely until she and Poseidon had sex in Athena’s temple. Athena punished her for this violation by turning her into the monstrous, stony-glanced creature that we know: those who gazed into her eyes would immediately turn to stone.

While ancient Greek vase-painters and relief carvers imagined Medusa and her sisters as having monstrous form, beginning in the fifth century they started to envisage them not only as terrifying but also as very beautiful women.

2. Griffin

The griffin is a legendary creature with the body, tail, and back legs of a lion; the head and wings (and at times front feet as well) of an eagle. In the Middle Ages, the griffin was thought to be an especially powerful and majestic creature, known since classical antiquity as the guardians of treasures and priceless possessions. In medieval heraldry, the griffin became a Christian symbol of divine power and a guardian of the Almighty.

3. Centaur

The centaur is a monster in Greek mythology, with human upper body with torso, hands and head, and horse lower body, including torso and legs.

4. Xing Tian (Corporal punishment)

Xingtian was an official under Yandi. Yandi fought against Huangdi for the position of supreme god, but he lost the conflict. Xingtian still continued the fight after Yandi’s defeat, but was vanquished and decapitated by Huangdi. Eventually, he regenerated himself and continued his defiance brandishing his shield and ax, using his nipples as his eyes and his navel as his mouth.

5. Xuan Wu (Black Warrior of the North)

The Black Tortoise or Black Turtle is one of the four symbols of the Chinese constellations and it’s usually depicted as a turtle entwined together with a snake. In East Asian mythology it is not called after either animal but is instead known as the “Black Warrior” under various local pronunciations. It represents the North and the winter season—thus it is sometimes called Black Tortoise of the North (Chinese: 北方玄武; pinyin: Běifāng Xuánwǔ).

In Japan, it is one of the four guardian spirits that protect Kyoto on the north. It’s represented by the Kenkun Shrine, which is located on top of Mount Funaoka in Kyoto.

6. Jiutouniao (Nine-headed phoenix)

The nine-headed bird, also called the “Nine Phoenix,” is one of the earliest forms of the Chinese phoenix. It was worshipped by ancient natives in Hubei Province, which during the Warring States period was part of the kingdom of Chu (楚). Due to the hostile relationship between the Kingdom of Chu and its former overlord, the reigning Zhou Dynasty, the nine-headed bird, being the totem creature of the Chu people, was demonized as a result.

7. Qiong Qi

Qiong Qi is a mythological Asian creature with a tiger body, buffalo horns, and bird wings, who often flew over the fights and ate people’s heads off the “right” side, siding with the evildoers or those in the “wrong” side. When someone committed an evil deed, Qiong Qi captured beasts to offer in their honor and encouraged them to do more evil deeds. The ancients considered him an evil creature with no feelings.

8. Hundun (Chaos mythical)

“Chaos” is a mythological term that is widespread all over the world. The pinyin is hùndùn and its meaning varies in different parts of the world. In Greek mythology and in many other traditions, Chaos is the god who originated the cosmos. At the beginning, everything was connected, that is, in a state of chaos, until the various elements were separated. When Chaos died, his body turned into mountains and rivers of the earth we know now.

Section 2

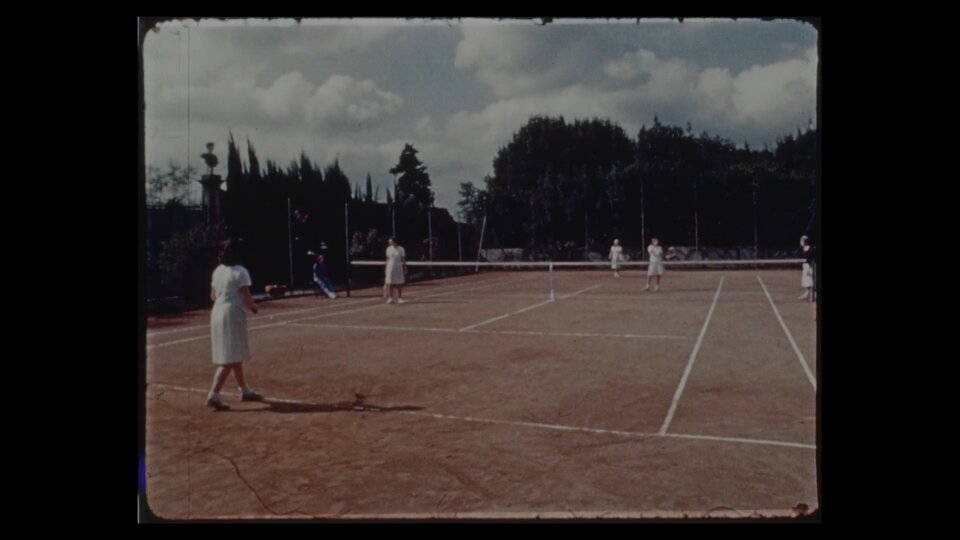

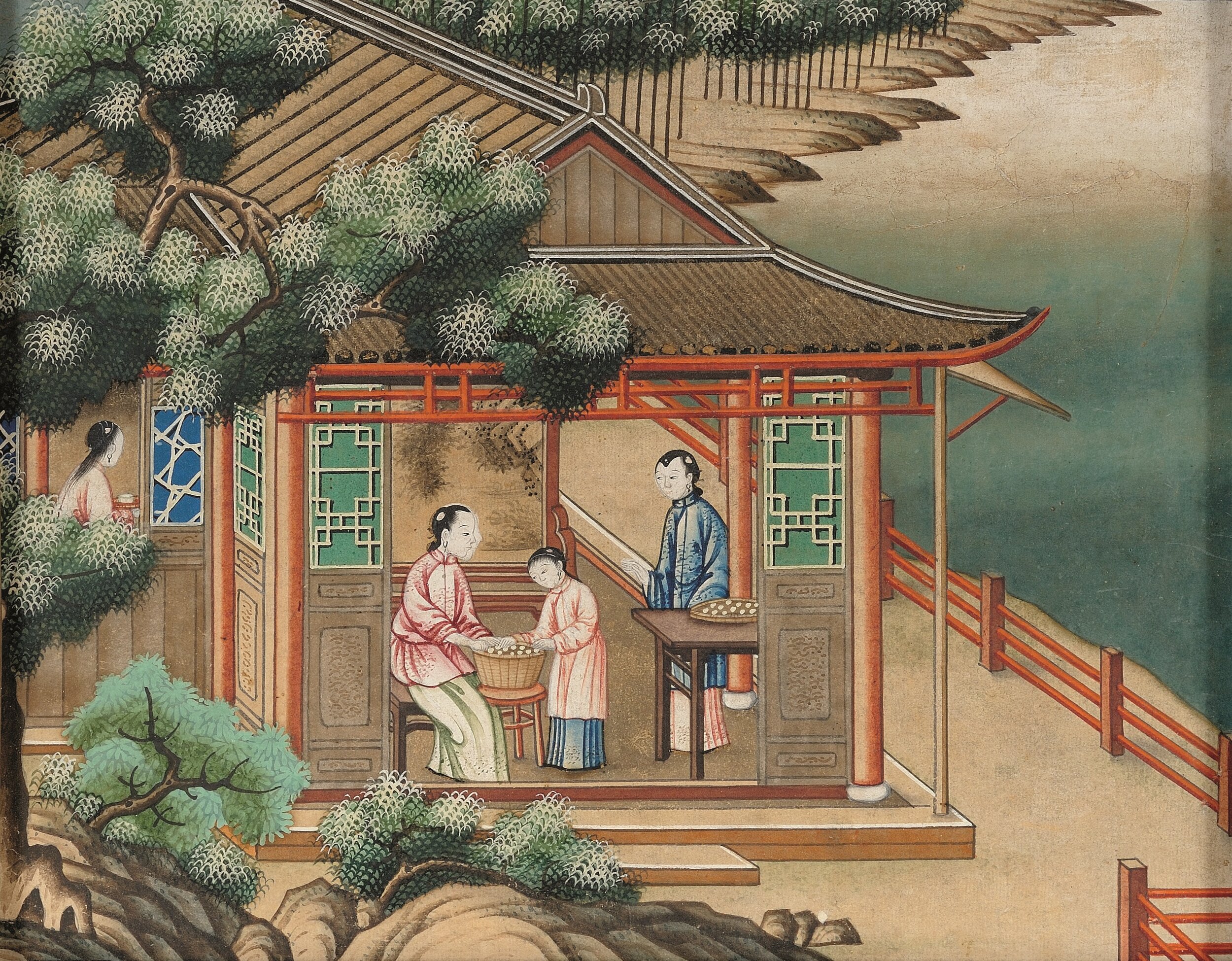

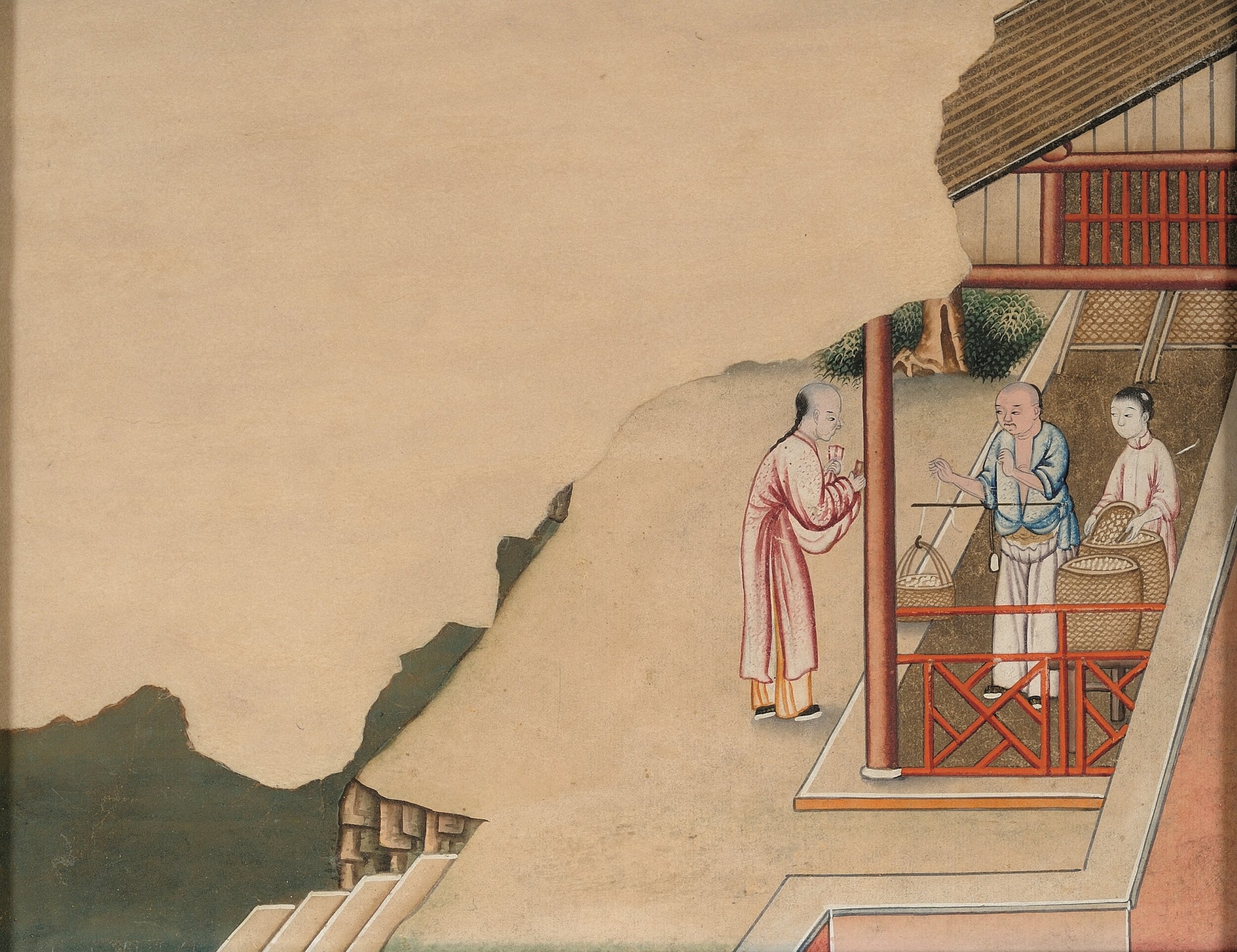

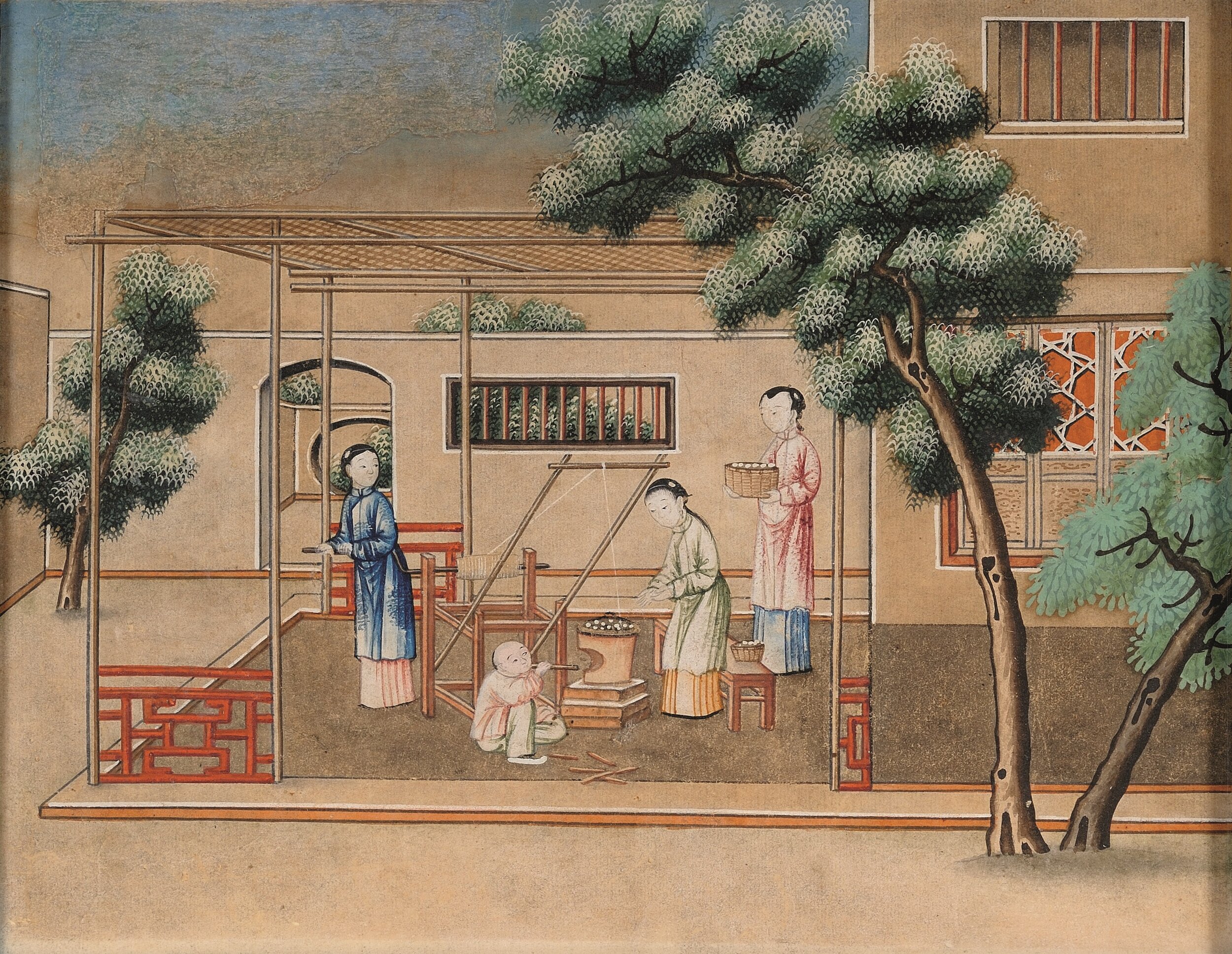

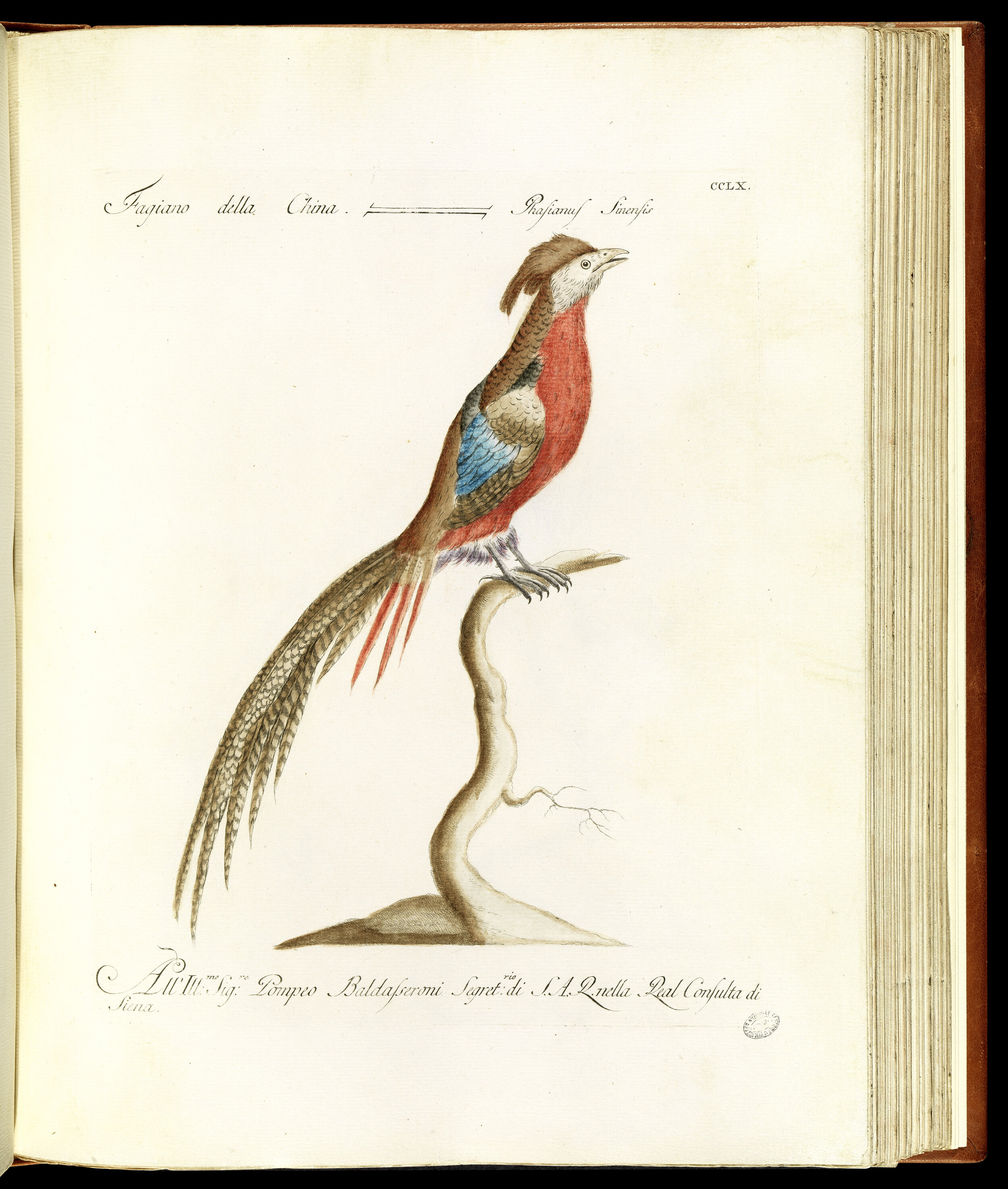

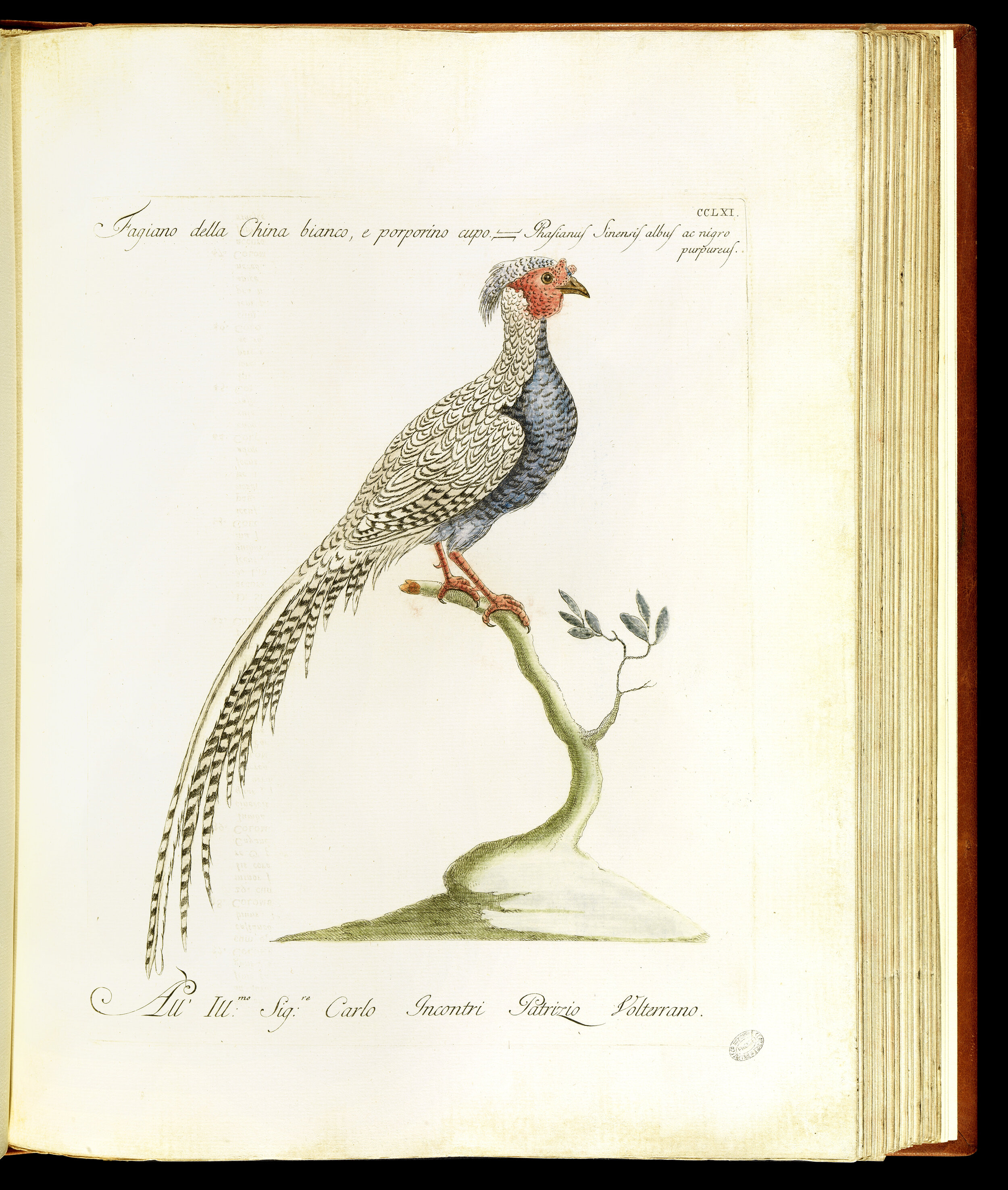

The fascination of China at Villa del Poggio Imperiale

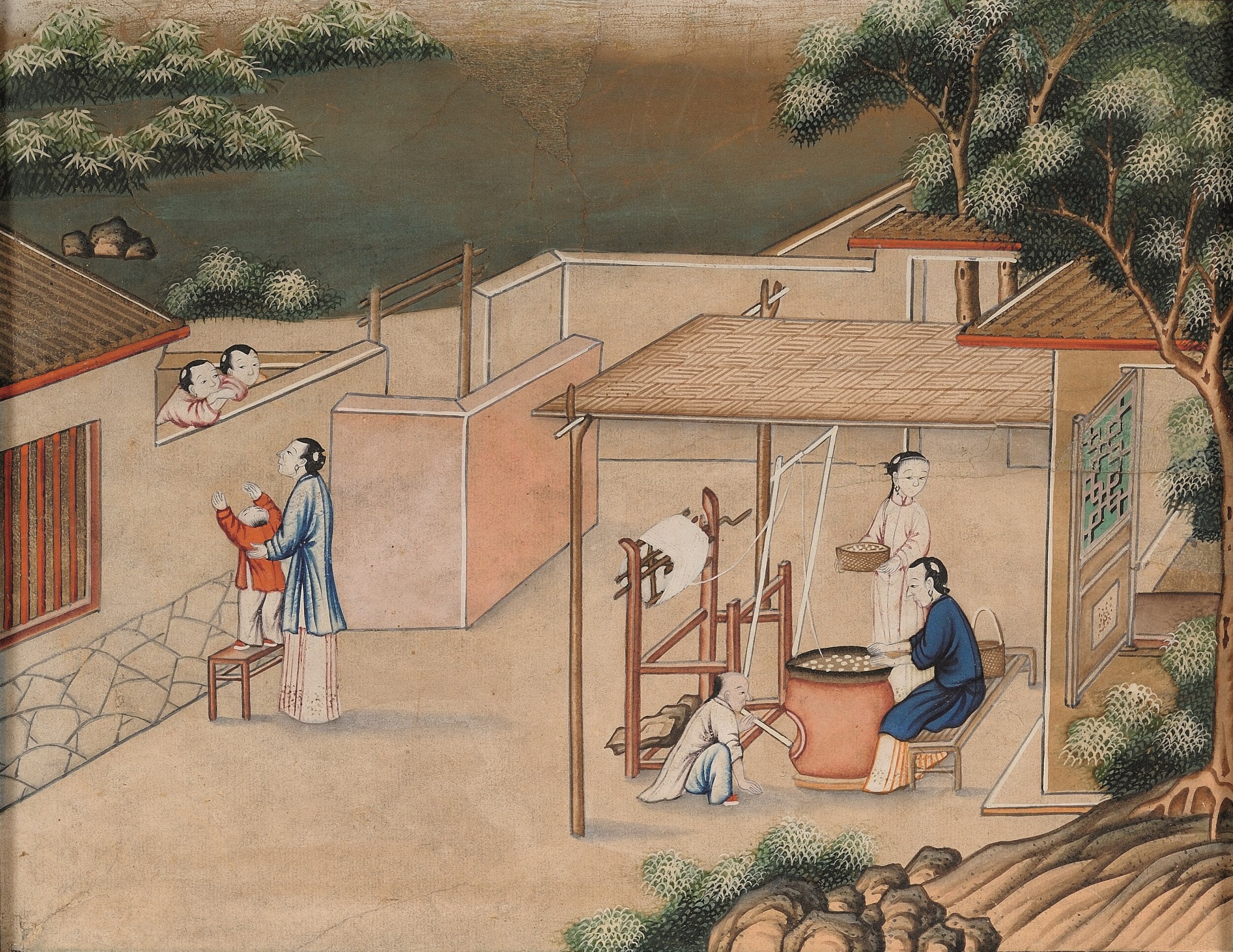

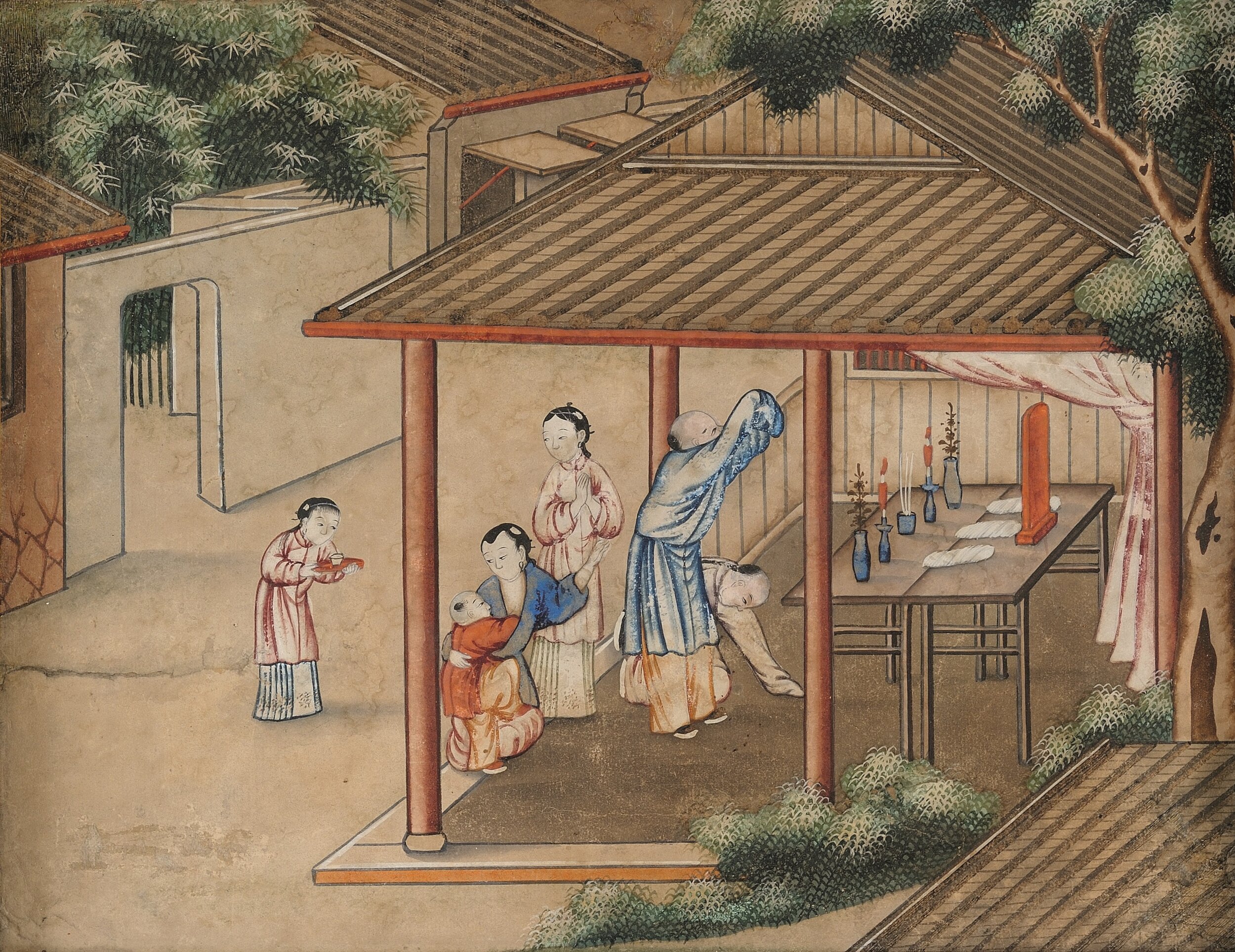

Fulvia Ferragamo’s passion for silk and Oriental decorative motifs may be traced back to October 1960, when she started attending the internationally renowned SS. Annunziata boarding school at Villa del Poggio Imperiale in Florence. The students, who came from all over the world, slept in dorms in what was known as the “Chinese quarter”, a wing of the house that bore witness to the popularity of China across Europe during the eighteenth century. Grand Duke Peter Leopold of Lorraine and his wife Maria Luisa also fell into the thrall of this fashion when they came to Florence in 1765 and chose Villa del Poggio as their summer residence. The apartment was furnished with wallpaper and paintings of various sizes from China, representing flowers and birds, character duos in Chinese interiors, and China’s most important production cycles for processing rice, tea, porcelain and silk. This iconographic repertoire offered exotic images of a faraway world for Westerners to dream about and admire. Well into the twentieth century, it held sway over these young female students, as we learn from the school newspaper Il Poggio: “To live, day after day, in this solemn and majestic palace-like country residence is to slowly and surely take possession of the secret soul of the place. Or rather, it would be more accurate to say that the place takes possession of us … that alongside the teachings and guidance of those who educate us in the Arts, Letters, History, etc., the evocative nature of this place contributes to the formation of our culture and taste.”

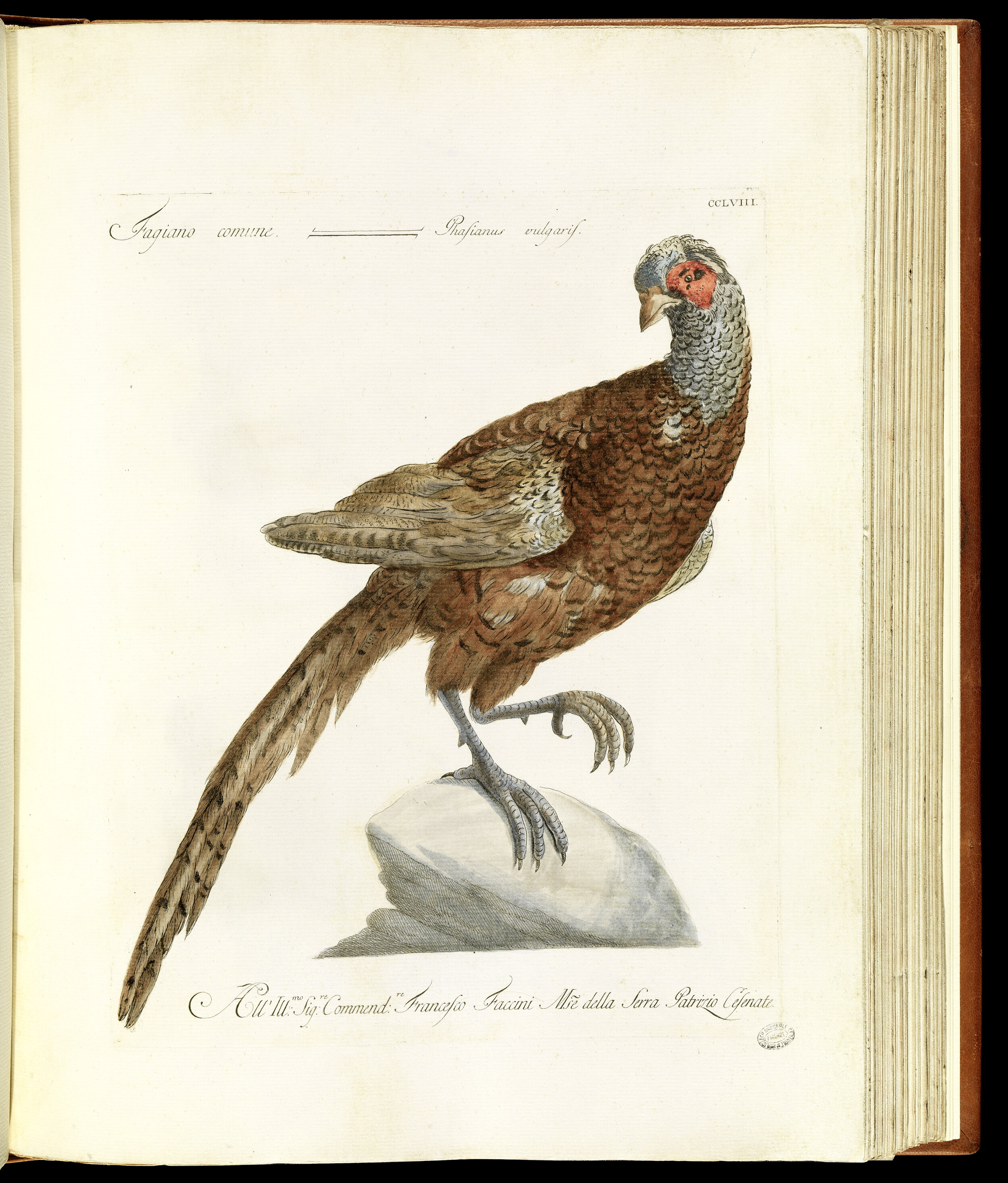

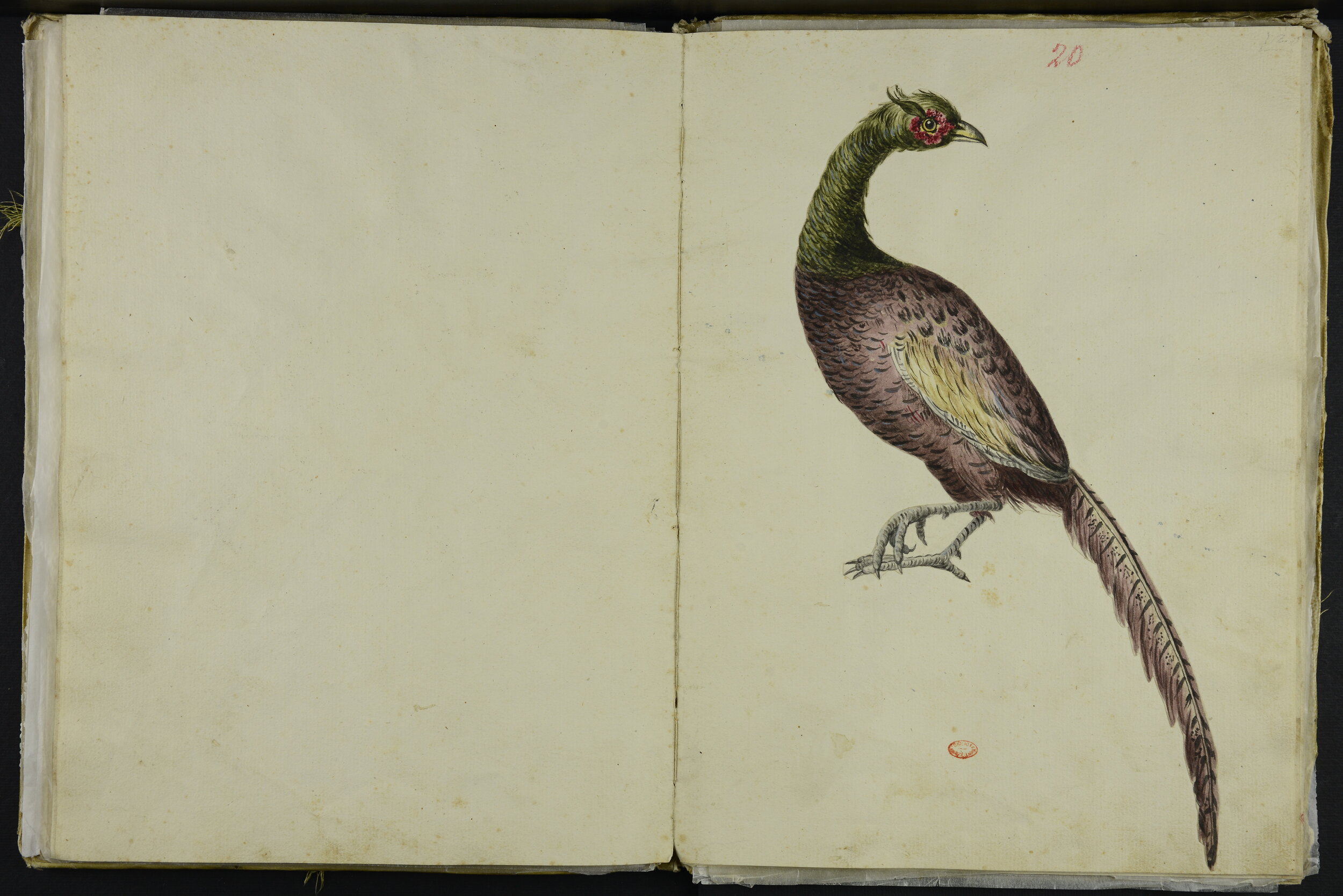

These memories would accompany Fulvia along her entire creative path, her imagination continually inspired by scenes from life in the “Chinese quarter,” among always-perfect characters, well-dressed even when toiling hard, among bird species, pheasants and partridges, and flowers, especially peonies decorating the walls, sparking Fulvia’s personal interest in travel (especially to China and to India), in photography, and in collecting curios and small antiques from these countries.

In this section an unpublished video from a private collection dated back October 1955 documents the students’ life at the Villa del Poggio Imperiale Girls boarding school.

Section 3

Inspirations

Countless sources of inspiration lie behind the subjects printed on these scarves and ties: from works of art kept in museums to ancient tomes on botany and the natural sciences, to be seen in libraries or encountered through more recent reprints. All of these sources were conveyed to the Ferragamo silk department in Milan in the form of drawings and collages. The initial moodboards for each collection, which are bound in a total of 1065 red albums, are filled with cut-out images glued with irreverent anachronism and in unexpected dimensions: a bee towers over a castle, a flower is far bigger than a shoe, a Persian miniature is re-enlarged, displaying remarkable skill in the resized details… The exotic and the biographical jostle one another in these albums.

Used with regularity from the 1970s on, these albums inspired the company’s in-house designers and the silk producers in Como, who had a close enough relationship with Ferragamo to merit first-hand access to the details of the designs they would be reproducing.

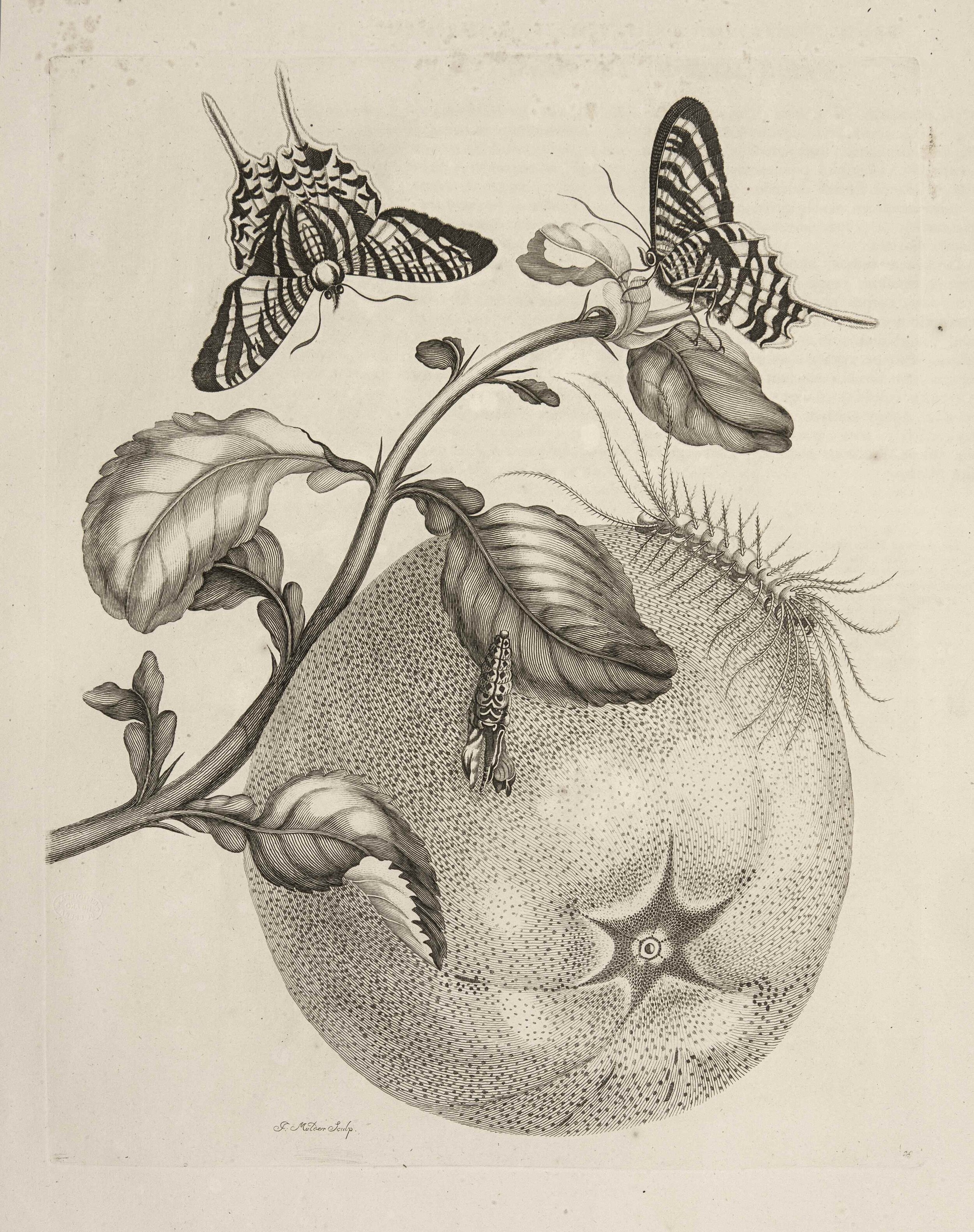

In preparation for this exhibition, references in the albums were cross-checked and matched against the designs of scarves that went into production. Surprising discoveries emerged. A samurai on horseback painted on a scarf wears armour identical to a suit in the permanent collection of the Museo Stibbert in Florence; the poppies that stand out on a 1990s print are a faithful reproduction of an engraved panel from one of the most beautiful botanical books in history, Basilius Besler’s 1613 Hortus Eystettensis. Many of the floral-themed scarves take inspiration from the magnificent flower garlands painted by the Medici painter Bartolomeo Bimbi in the seventeenth and eighteenth centururies and now preserved at Museo della Natura Morta in Poggio a Caiano (Prato).

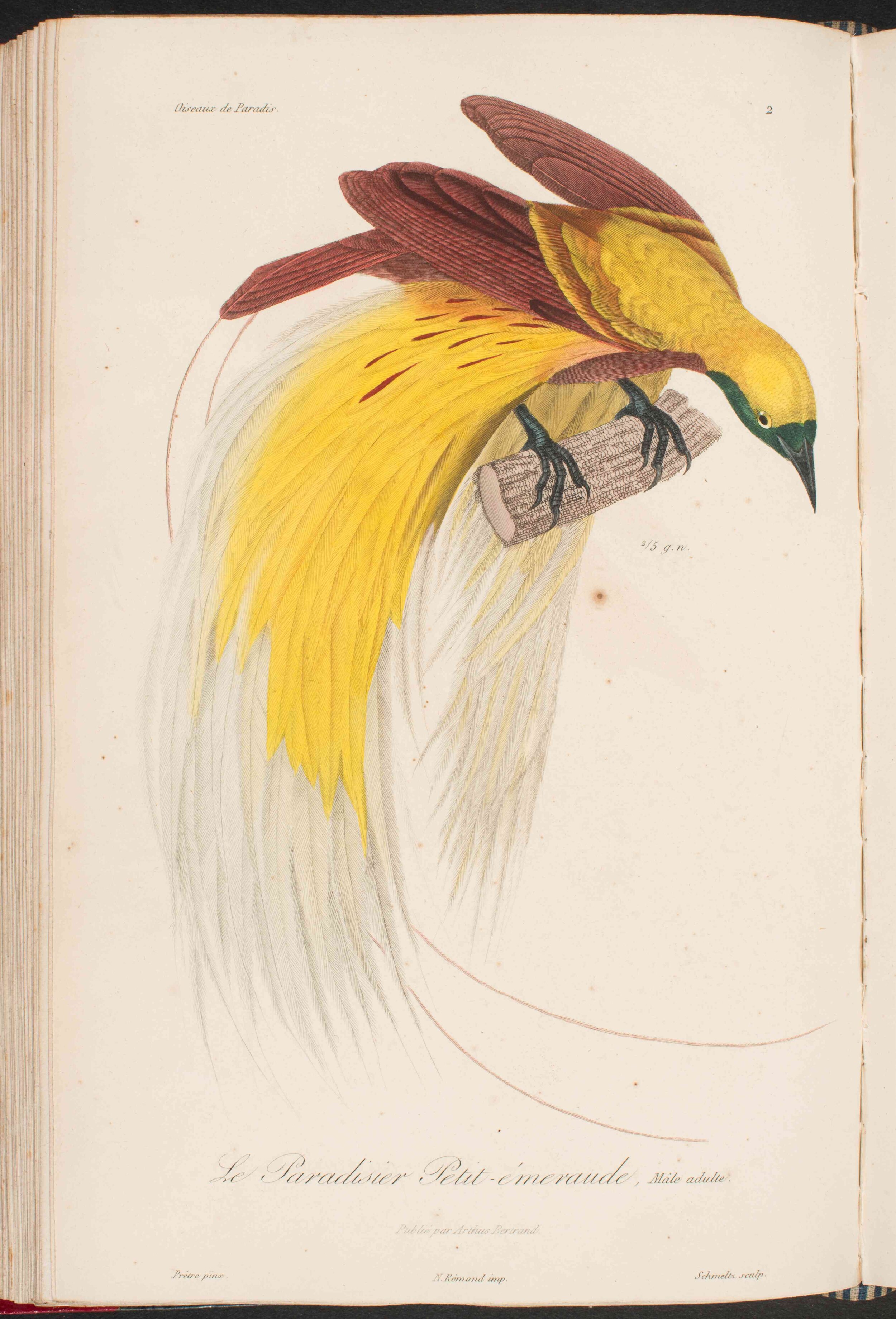

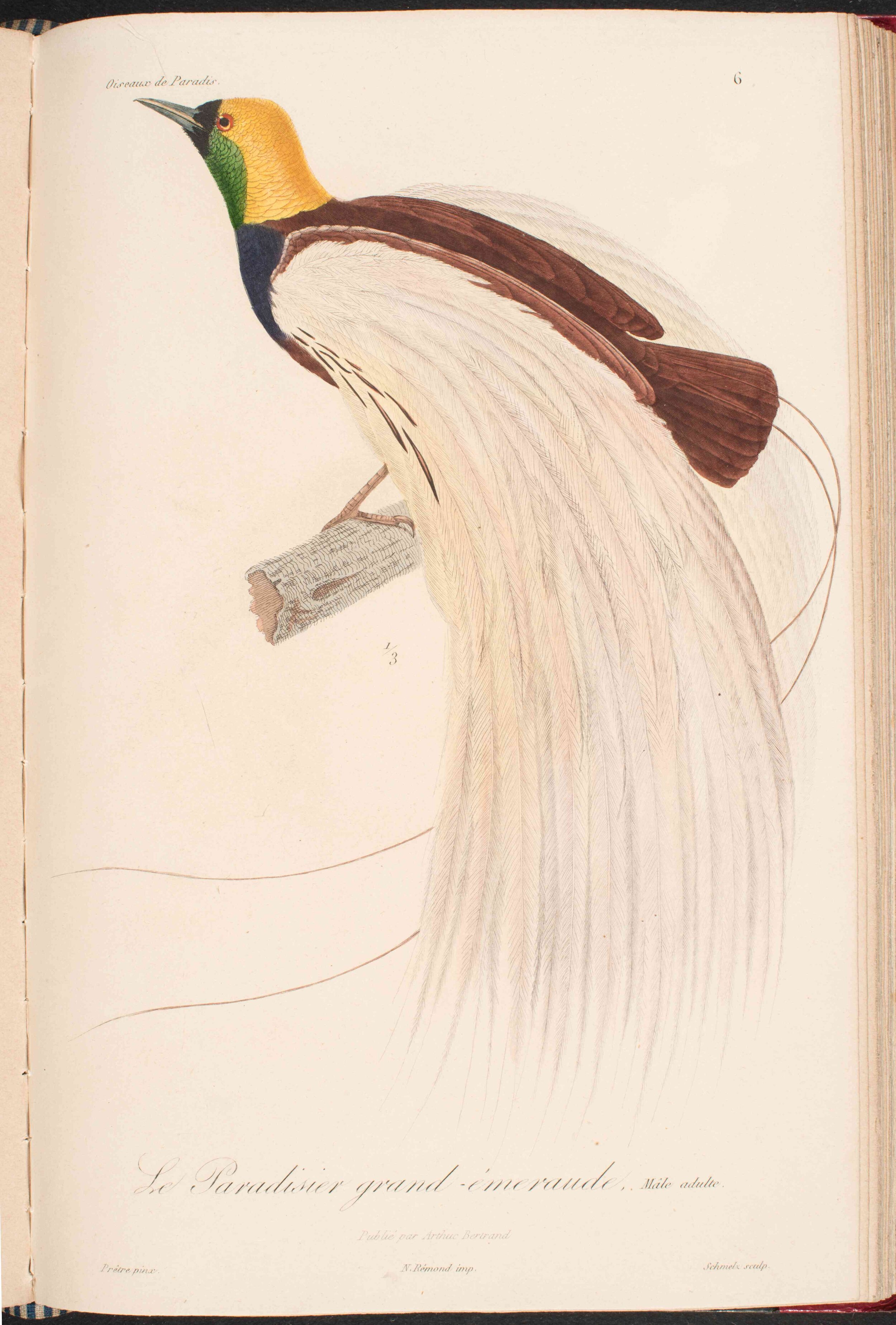

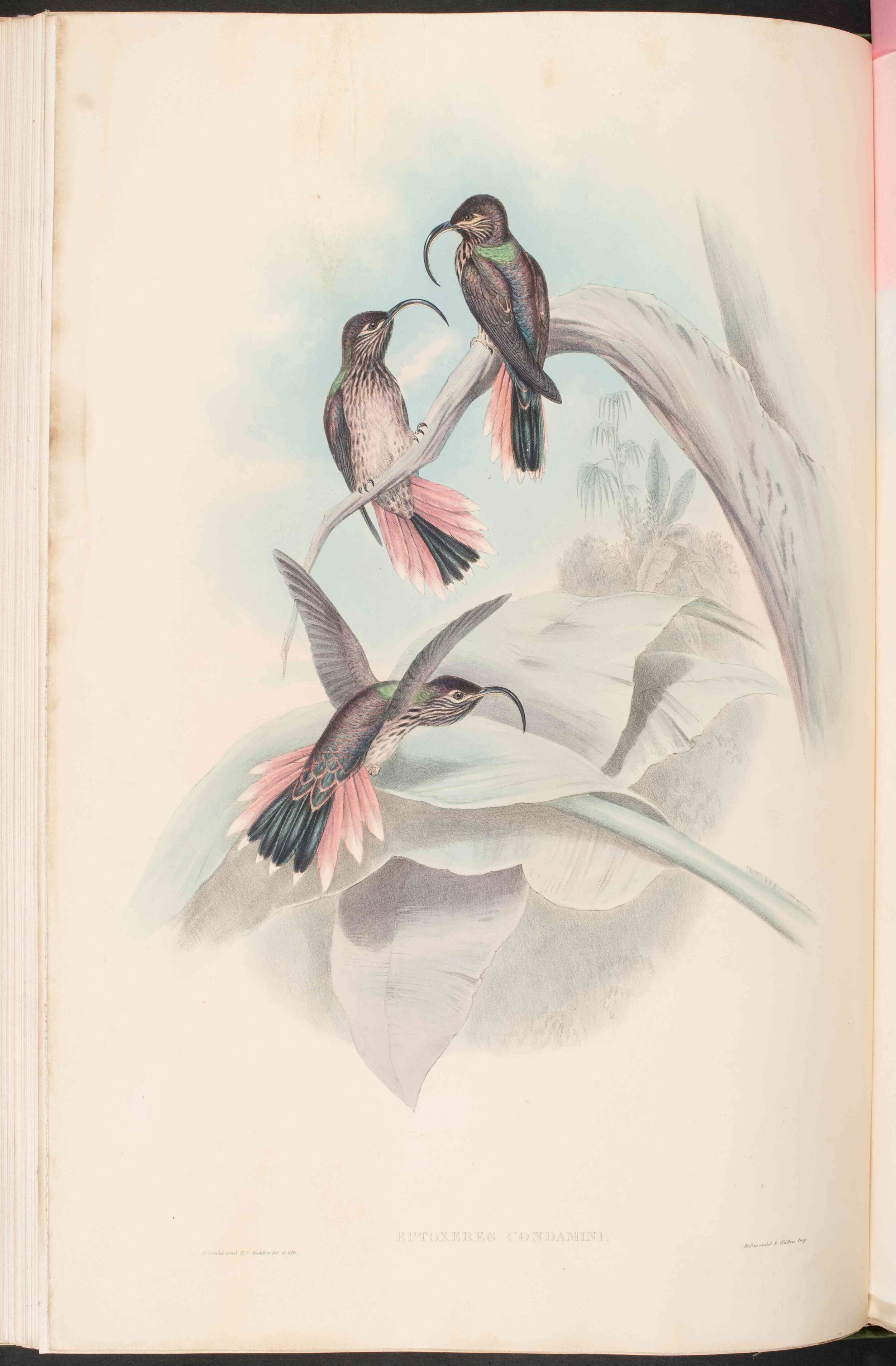

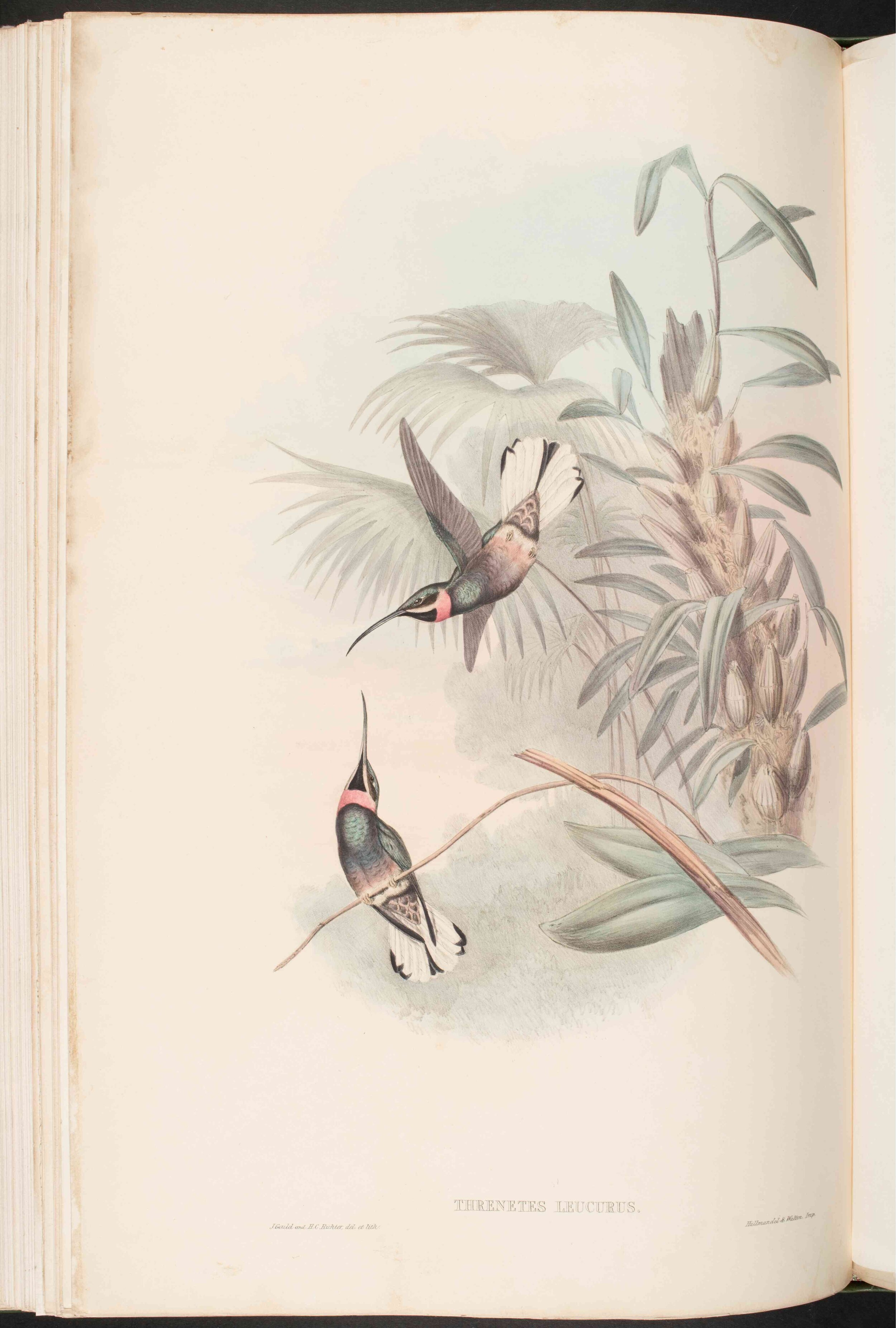

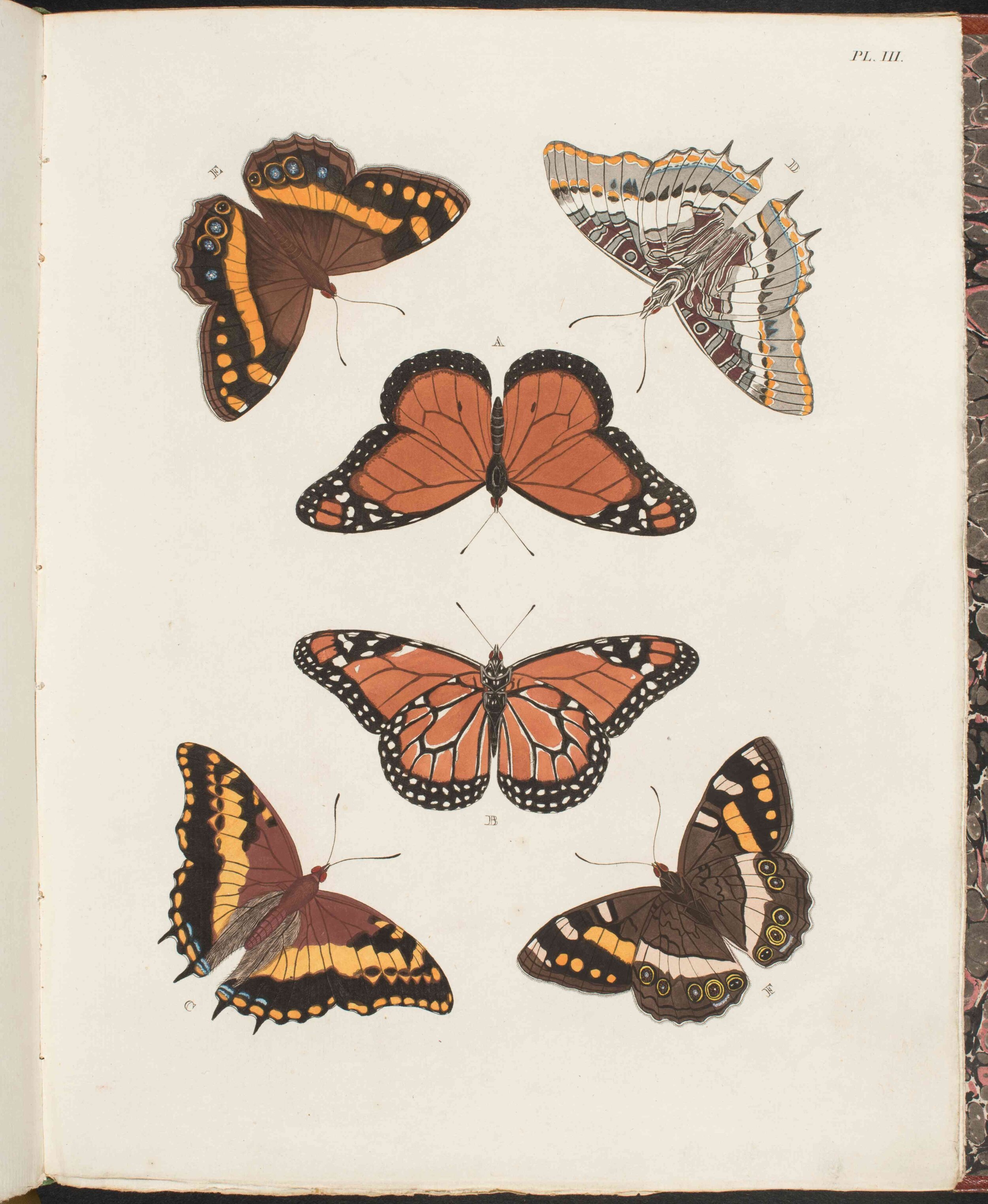

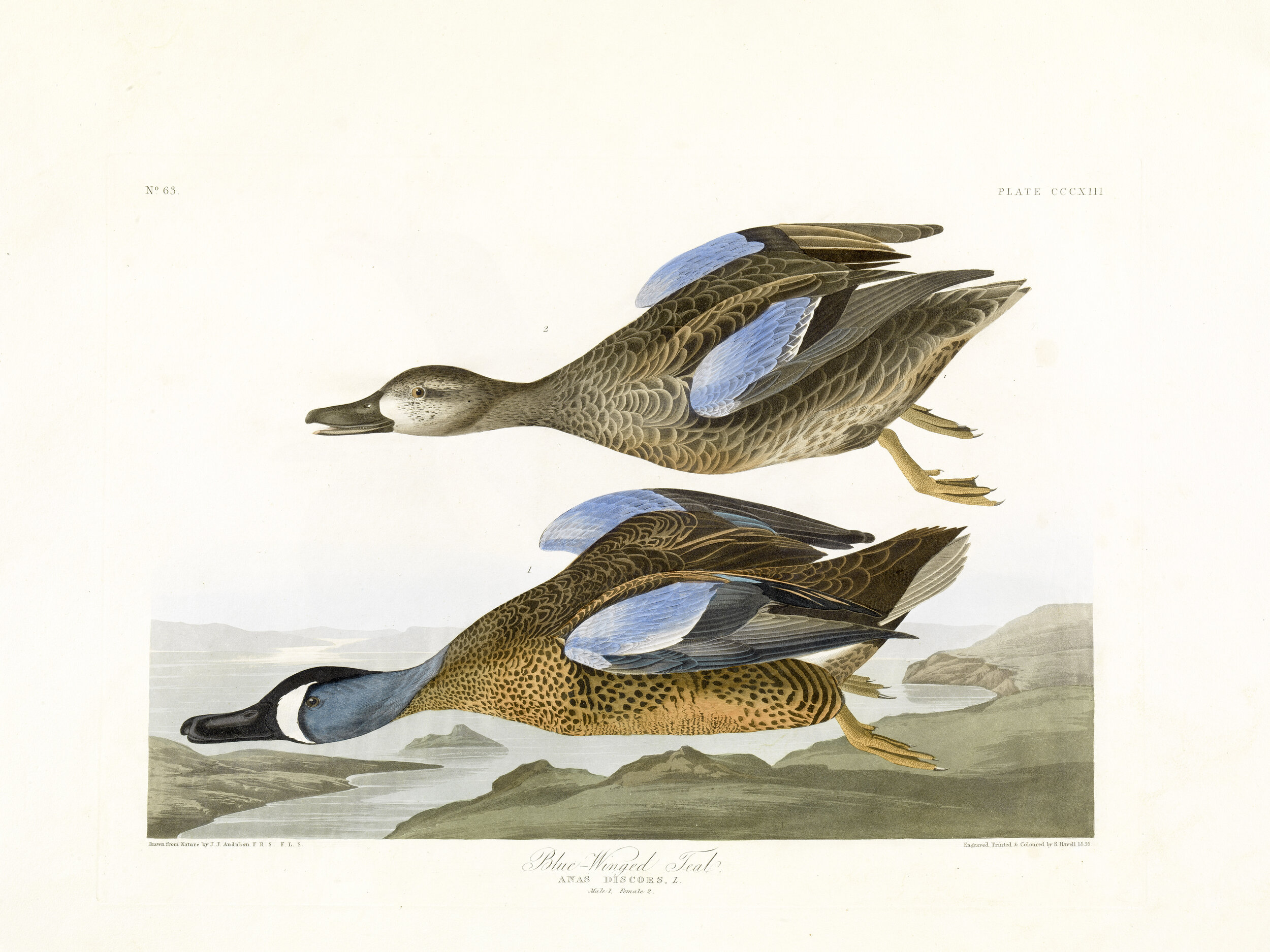

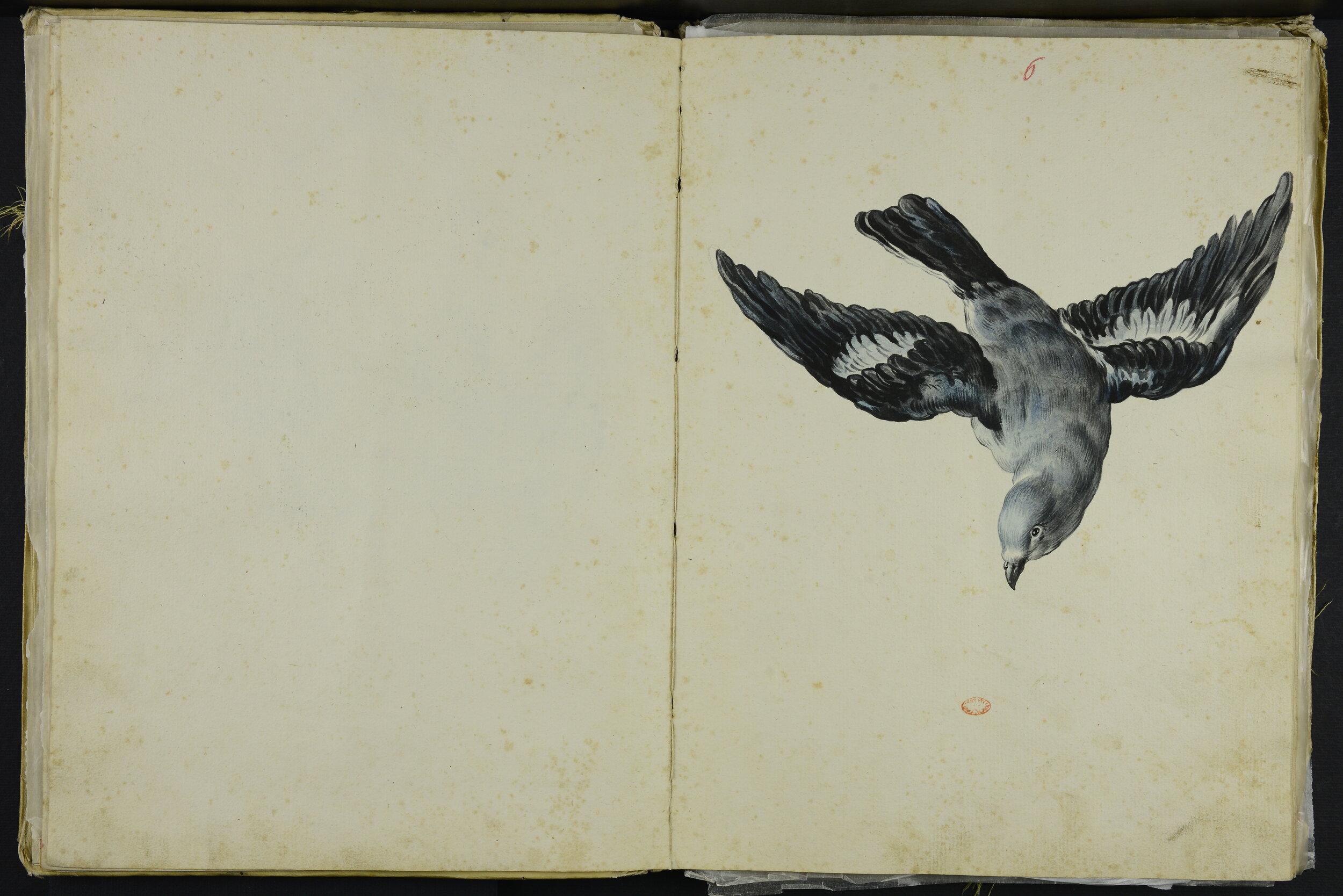

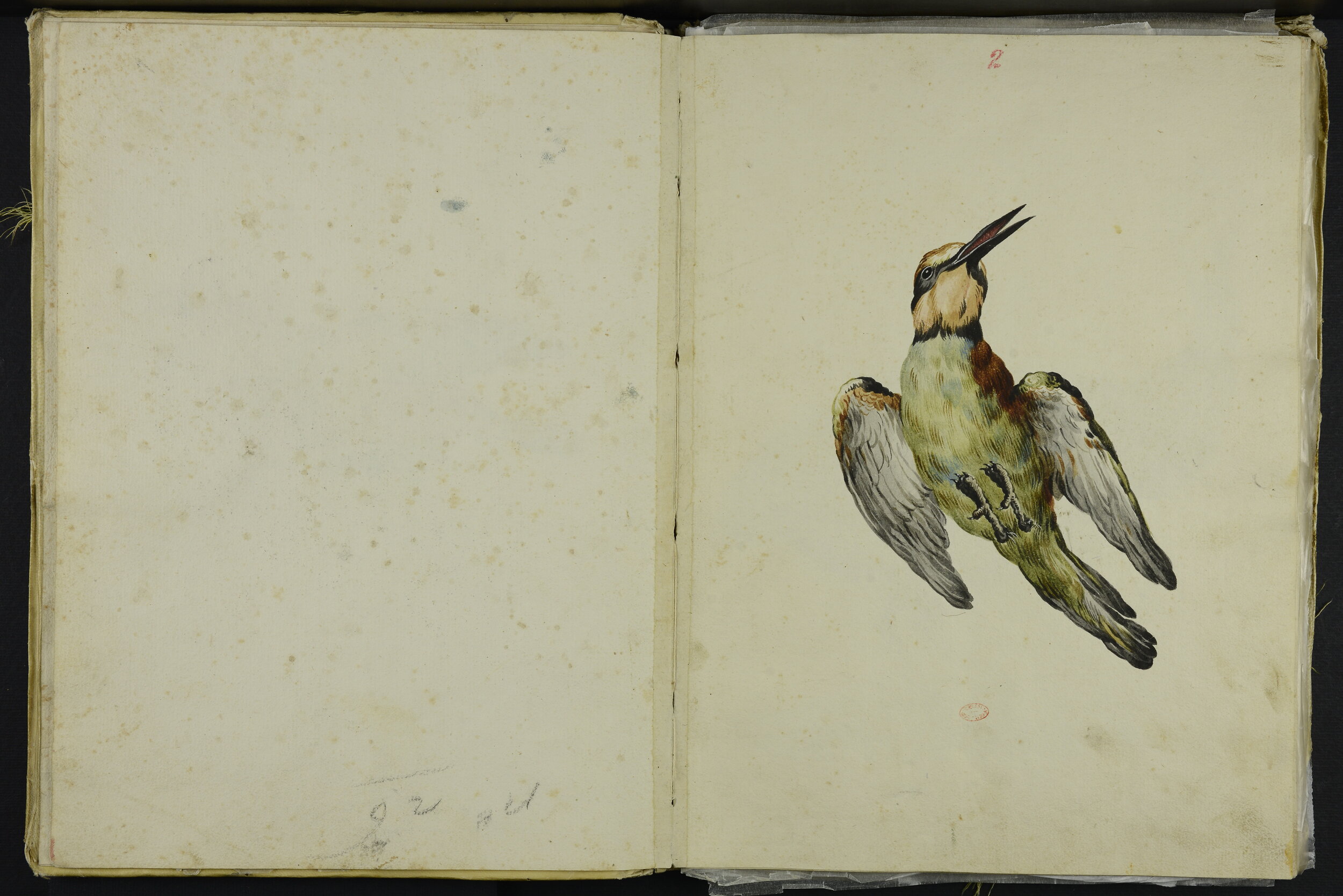

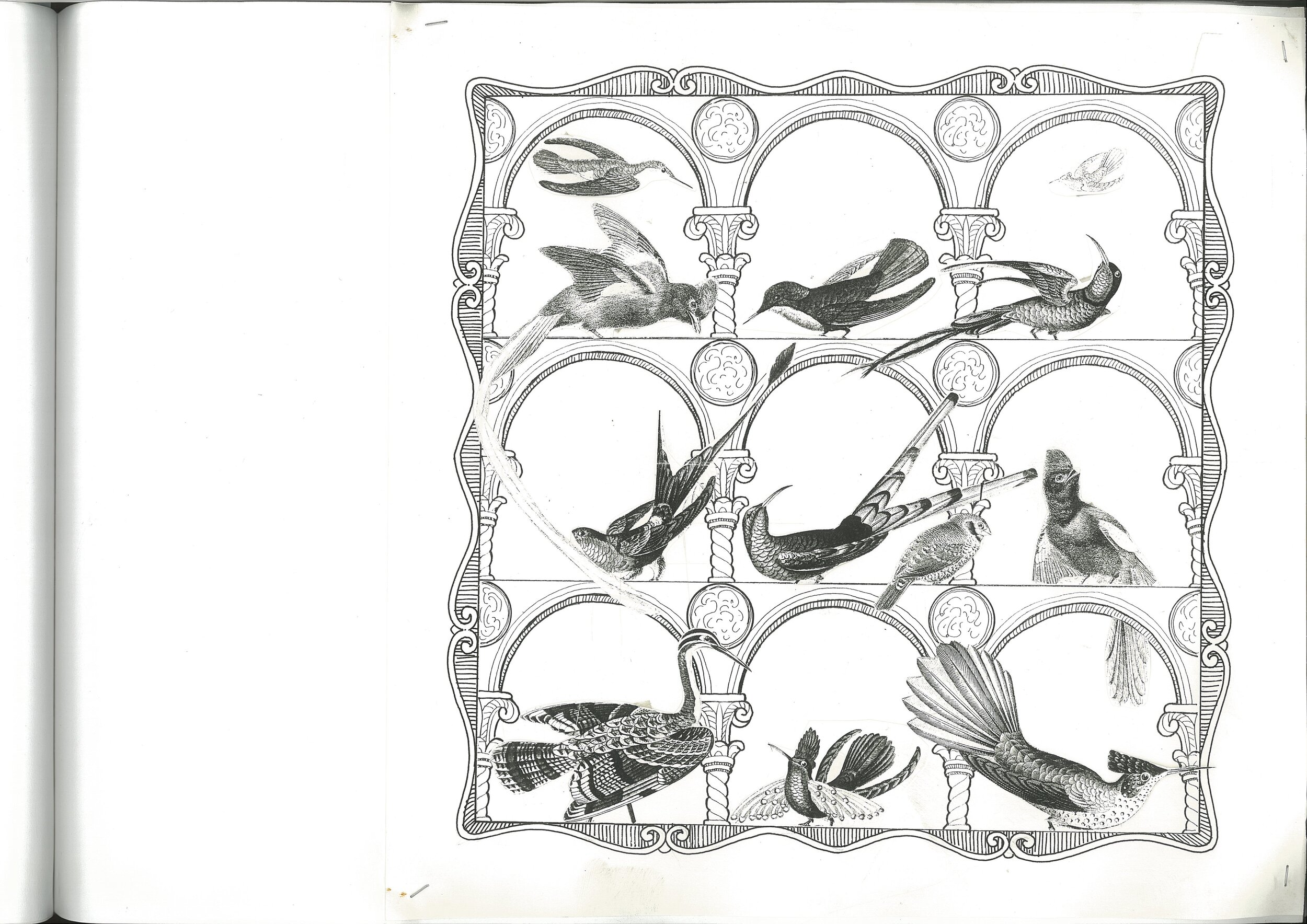

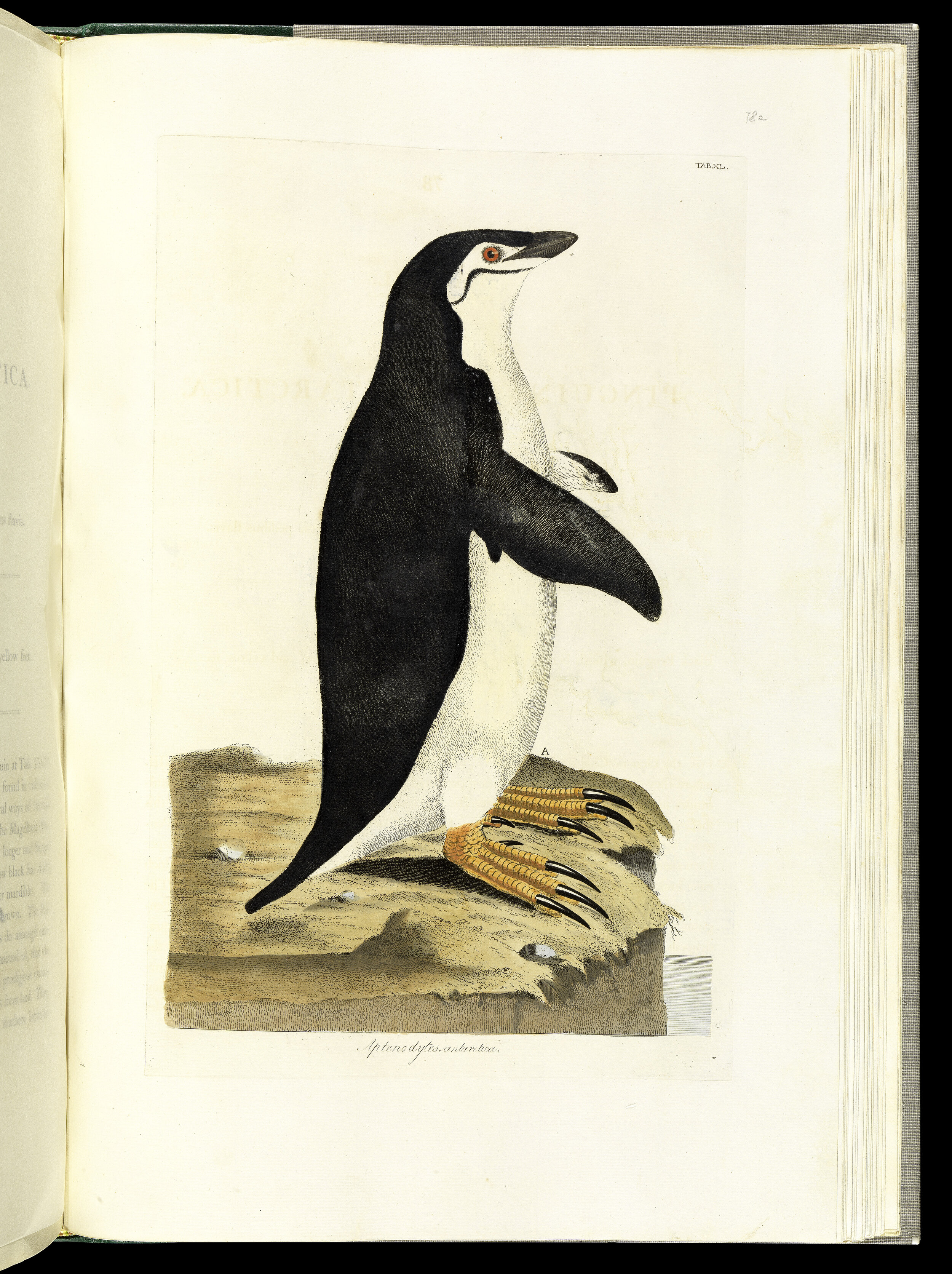

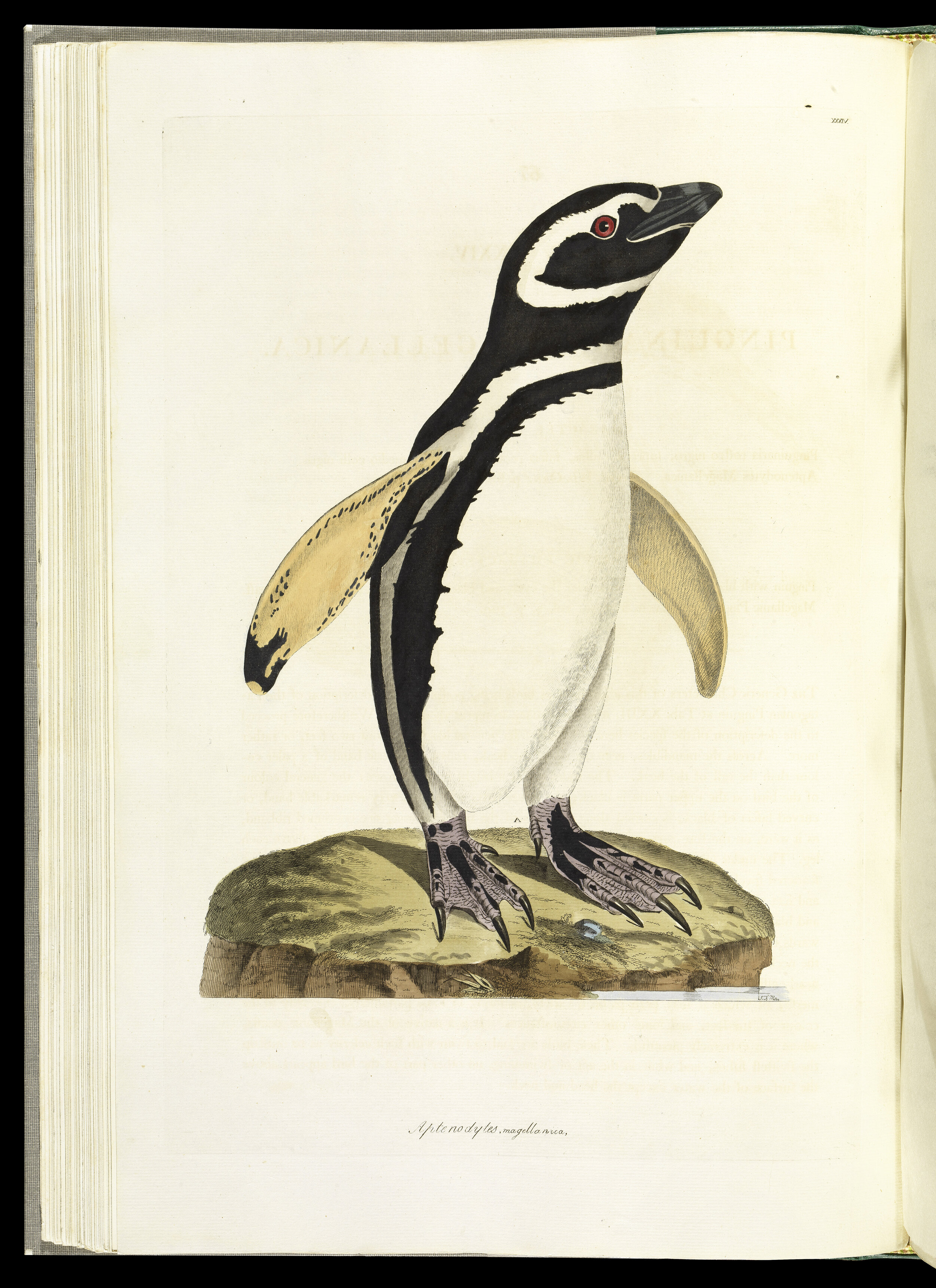

Without doubt, the most fascinating subjects to populate these prints are the birds. Silk ducks, herons, pheasants, penguins, and parrots lend their silhouettes and chromatic contrasts to Fulvia’s reinterpretations; she depicts them with elegant taste, with a poetic sensitivity that may only be conveyed by someone who has a love of these animals, who is accustomed to admiring their lively, festive manifestations in real life. Fulvia’s lifelong passion for avifauna began with her stays at the Torre Trappola estate, in all seasons a place of extraordinary beauty and emotion in the Maremma region near Grosseto. In addition to direct observation, her ornithological creations frequently drew on centuries of iconographic heritage, in the form of great published masterpieces and popular contemporary magazines. Subjects from John James Audubon’s The Birds of America considered the most beautiful book of ornithology ever published (and today the most expensive) are much in evidence. Printed in London between 1827 and 1838, the book’s four monumental volumes feature 435 aquatinted, engraved, and hand-colored plates of some 1065 species, depicted at life size. Audubon’s decision to work to natural scale meant that he had to come up with some imaginative compositions in order to depict larger birds in poses that would fit onto the sheet of paper. A problem much understood by the designers who drew these scarves, who were happy to imitate the great ornithologist’s graphic solutions.

Section 4

Flowers

The formal cipher of Fulvia’s early scarves, adopted in 1971 and continuing for fully twenty years, was for the most part a patchwork of flowers and leaves used to assemble multiple decorative motifs. We cannot say with certainty where Fulvia drew her inspiration for this type of composition, but we do know that this choice was aesthetically related to the centuries-old baroque tradition of infioratas (flower decorations used at religious events, held to this day to celebrate the feast of Corpus Christi in small towns up and down Italy) and to the tradition of Giuseppe Arcimboldo’s burlesque portraits, in the sixteenths century, made out of flowers, fruit, and vegetables. Furthermore, it cannot be ruled out that Fulvia was influenced by the uppers of shoes her father made through the patchwork technique, sewing together small pieces of different leathers, often in contrasting colours. Likely, the maison’s shoes exerted a certain sway over Fulvia when, as a young entrepreneur in her twenties, she went looking for details to use to make Ferragamo’s silk prints unique.

Albertina Porro, a creative consultant at Butti e Ostinelli, the Como-based printing house that at the time worked exclusively for Ferragamo, says that the spark came from animated movies by great directors from Eastern Europe, which appeared on Italian broadcast TV between the autumn of 1970 and the spring of 1971 in prime time, on the RAI 2 show Mille e una sera. These included films by the “Czechoslovakian Walt Disney” Jiří Trnka, whose characters, especially in his 1959 A Midsummer Night’s Dream, moved against backgrounds and were dressed in costumes made of a patchwork of fruits, flowers, and leaves.

In the 1990s, floral themes featured in many silk prints: flowers in bouquets on trellises, garlands, flowers in vases, in a chequerboard, trapezoidal, rhombus, circle or ray-inspired shape, in a blaze of green, a botanical orgy of outsized flowers reproduced almost at natural size.

Born and educated in Florence, Fulvia was acquainted with the city’s libraries and its art and naturalistic collections, which provide us with a privileged observation point for delving into the creative nourishment for her decorative motifs. Suffice it to mention Museo di Storia Naturale (Botanica) of Florence, and its extraordinary collection of exotic wax plants, presented in delightful eighteenth and nineteenth centuries vases made by the Ginori factory, revealing the naturalistic interests of Pietro Leopoldo of Lorraine. Here the colours, the rendering of the petals and leaves, their imperfections and drops of nectar on the verge of falling are reproduced so brilliantly that observers believe they are actually looking at the real thing.

Section 5

Look back Anouk

This short film by young directors Rocco Gurrieri and Irene Montini draws its inspiration from the figurative world of the scarves created by Fulvia Ferragamo as well as from animated films by Czechoslovakian director Jiří Trnka, whose patchwork flower puppets suggested the figurative style of early Ferragamo prints. A lonely girl in a palace suspended between sky and sea slips tenderly into the emptiness of her days, secretly composing a variety of fantastical worlds in which she may abandon herself to her fantasies.

Look Back Anouk is not just a title, it is an invitation to both the protagonist and the audiences to look back, recognize themselves and welcome the gentle, crystalline irrationality of childhood.

It is undeniable that the reference goes to reality beyond the mirror created by Lewis Carroll and to the enchanted forest of A Midsummer Night’s Dream imagined by William Shakespeare and transposed by Jiří Trnka in 1959 in a personal and suggestive version. Human and animal characters are the ones who drag us on these unusual journeys with a melancholic taste. Curious and a little lost they swim among the pages of strange stories, catapulted perhaps by mistake into the upside of reality, where dreams rest. The visions and sensations that torment Anouk making her predict the arrival of something mysterious and unknowable. They are nothing more than messengers and heralds in celebration, anxious for the vibrant ritual that is celebrated among the flowers of the forest. A magical and audacious strength is really revealed to her. Once the night is over, the dances are silenced and the fears are extinguished, all that remains is to to rock and shine with life, “Like tears, crying for their own shame”.

Section 6

Exotic animals

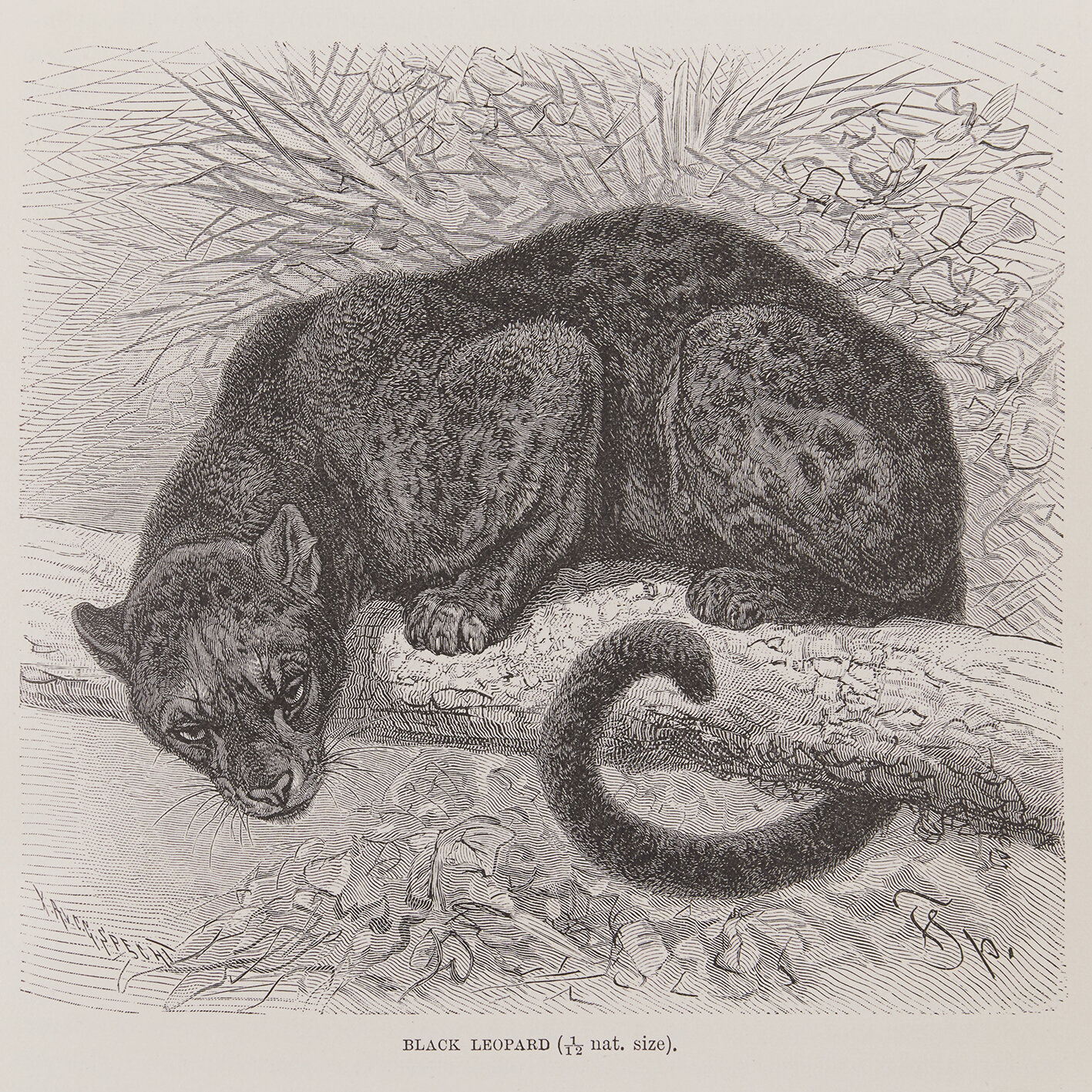

Since ancient times in the East, woven silk has been a support for zoomorphic representations. In Western culture, wildlife has also appeared on this precious weave, either painted or embroidered. These ancient traditions live on in the extraordinary animalier designs on Ferragamo scarves, where numerous animal species come to life, all clearly identifiable and traceable to precise taxonomic categories. Long a symbol of elegance and grace in movement, spotted felines predominate. A cultured connoisseur of her favorite subjects’ scientific and artistic iconography, drawing on the most diverse sources (ancient tomes and works of art and engravings from a variety of periods) Fulvia combined these precious references with direct observation, documented in snapshots that she took on her many trips abroad, supplemented by her knowledge of photo features in specialist magazines. Since the 1980s, the latter have been responsible of combining a passion for photography with an interest in nature, significantly developing a focus on animals and the environment through images, all at a time before the internet existed.

For her creations, Fulvia selected, re-worked and presented elements from everyday life: through a Pop prism, she drew on folklore, art, science and education, the combinations varying over the years depending on the graphic designers with whom she worked in different periods.

In her early decades, Fulvia reworked her subjects within floral mosaics and elegant compositions, using a soft-hued palette to highlight the fairy-tale atmosphere of her images. In later years, her focus shifted towards eye-deceiving striped and dotted pelts that offered a chance for bold experimentation, calling to mind the interpenetrating forms typical of Maurits Cornelis Escher’s paradoxical art.

Section 7

Young Talents on the Silk Road

At every exhibition, the Museo Salvatore Ferragamo sets aside space for young creatives to interpret the exhibition theme.

Art Media Studio has created this multimedia installation to showcase graphics designed by five students of the Liceo Artistico di Porta Romana and Sesto Fiorentino, Florence, under their teachers’ supervision.

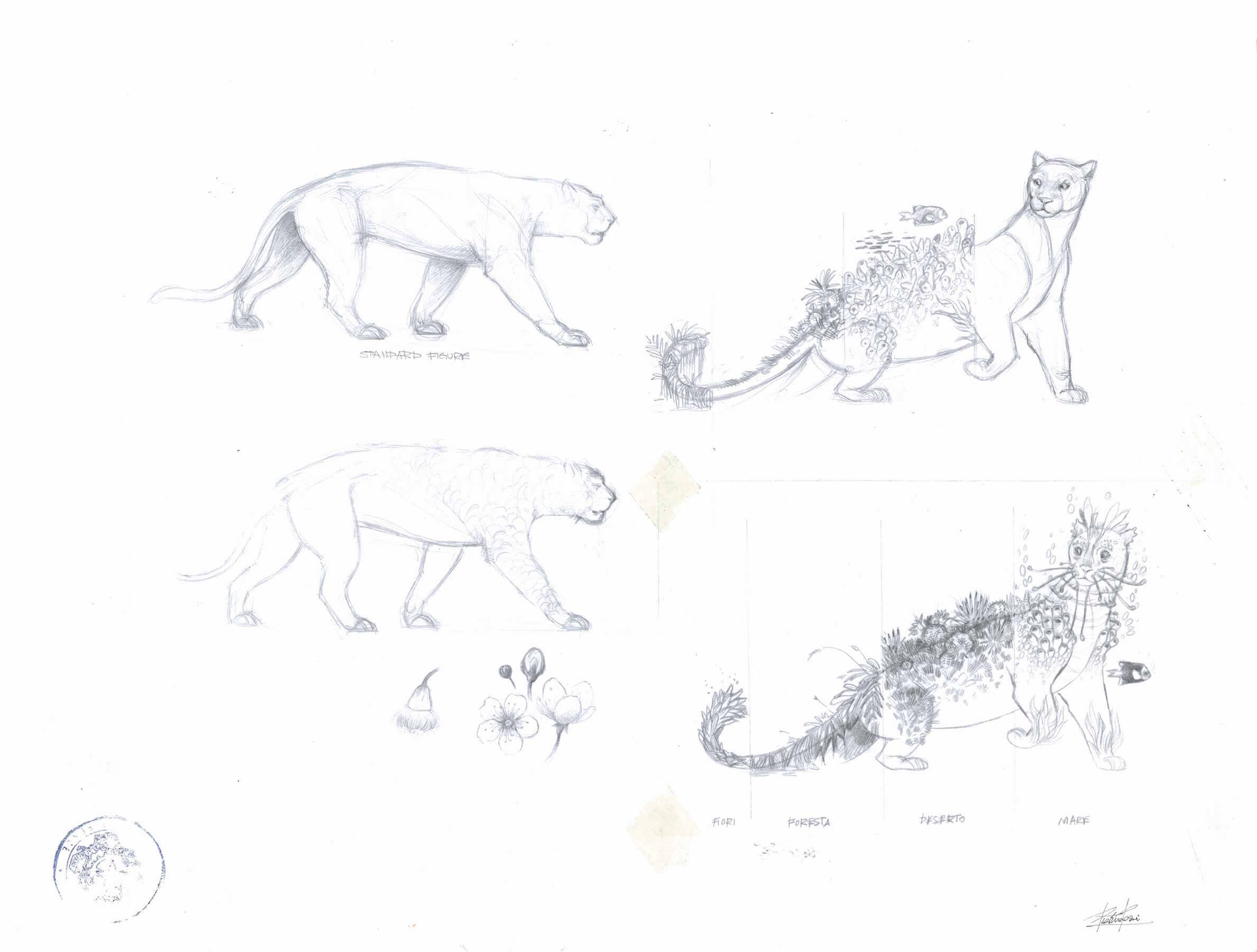

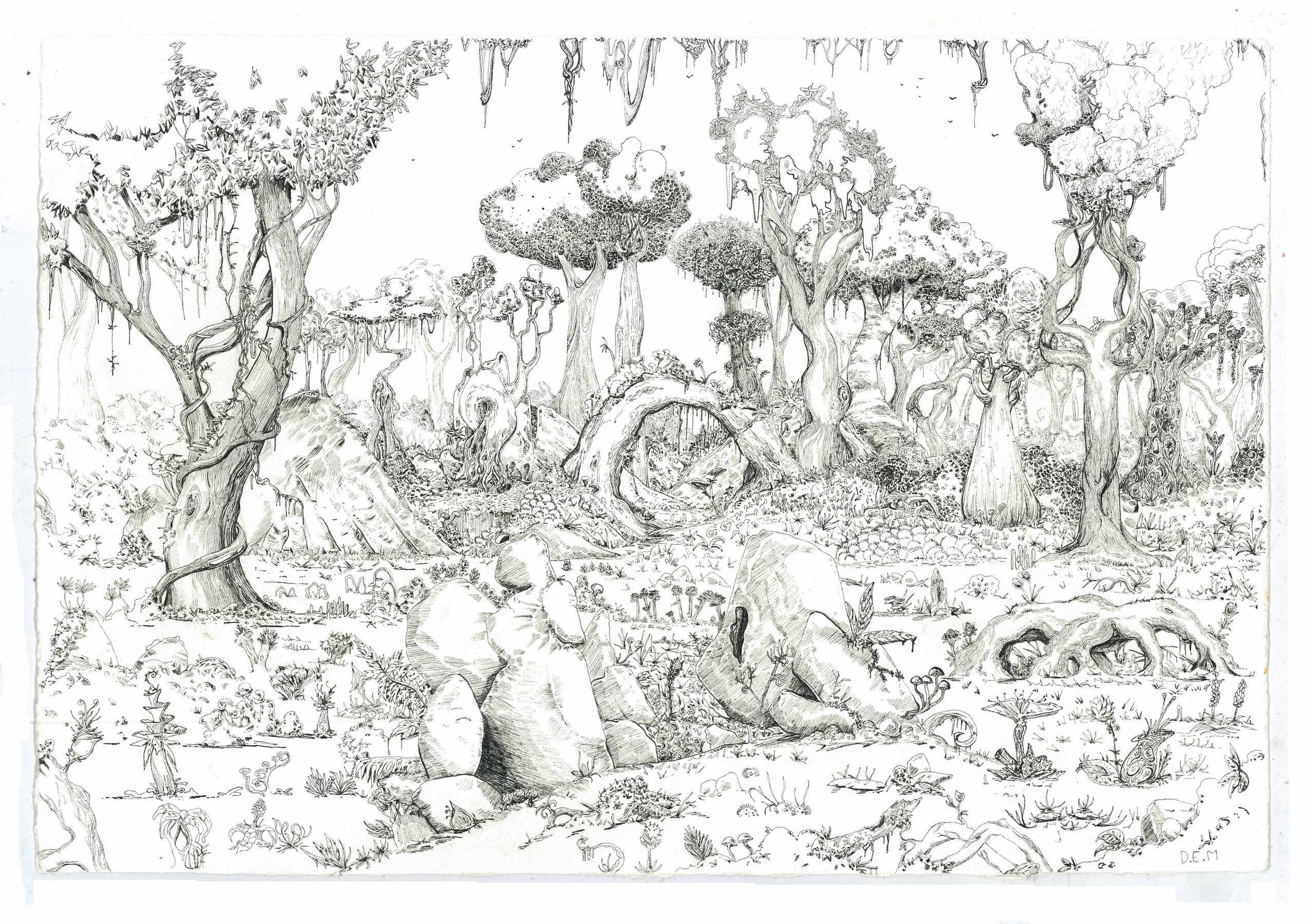

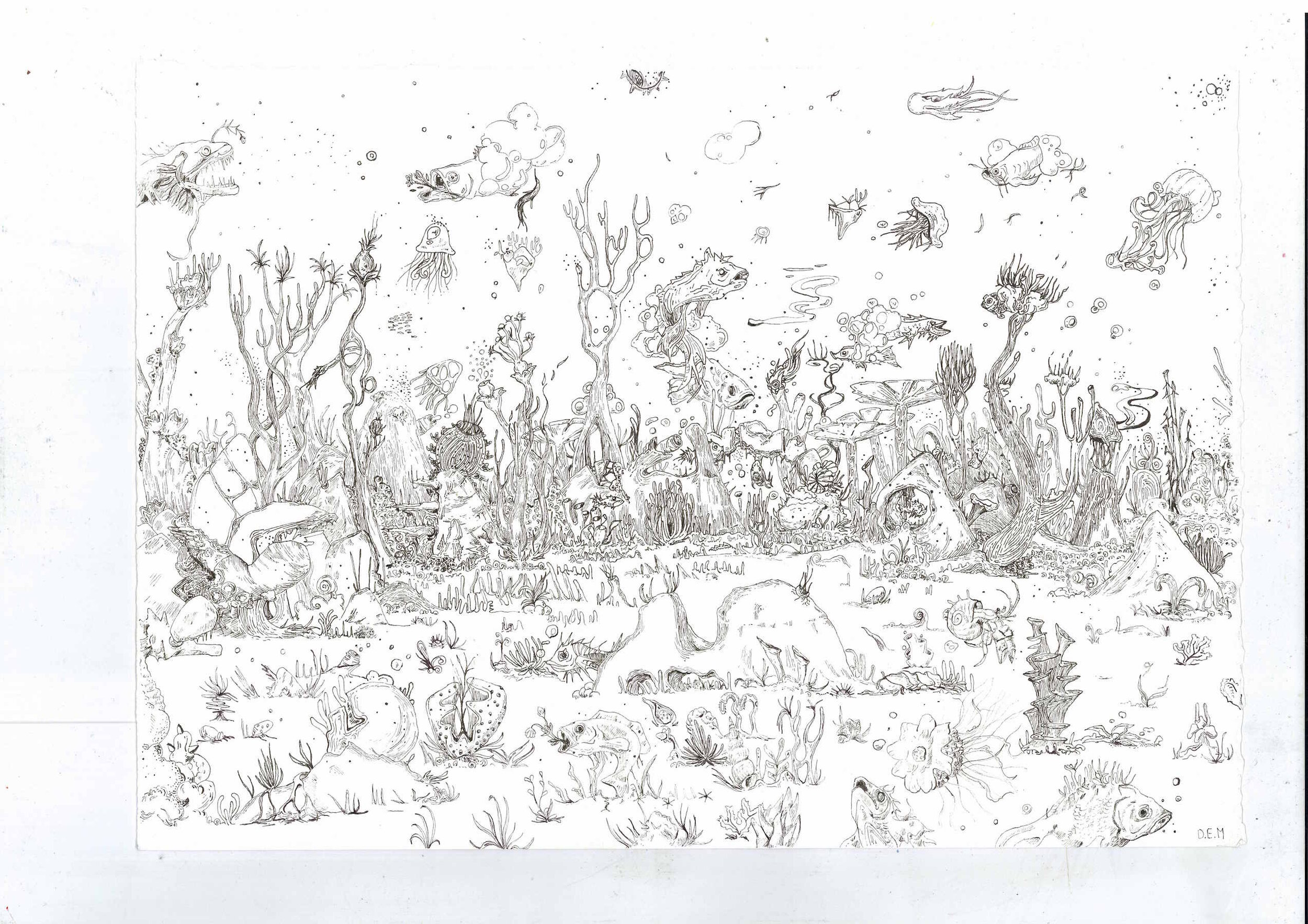

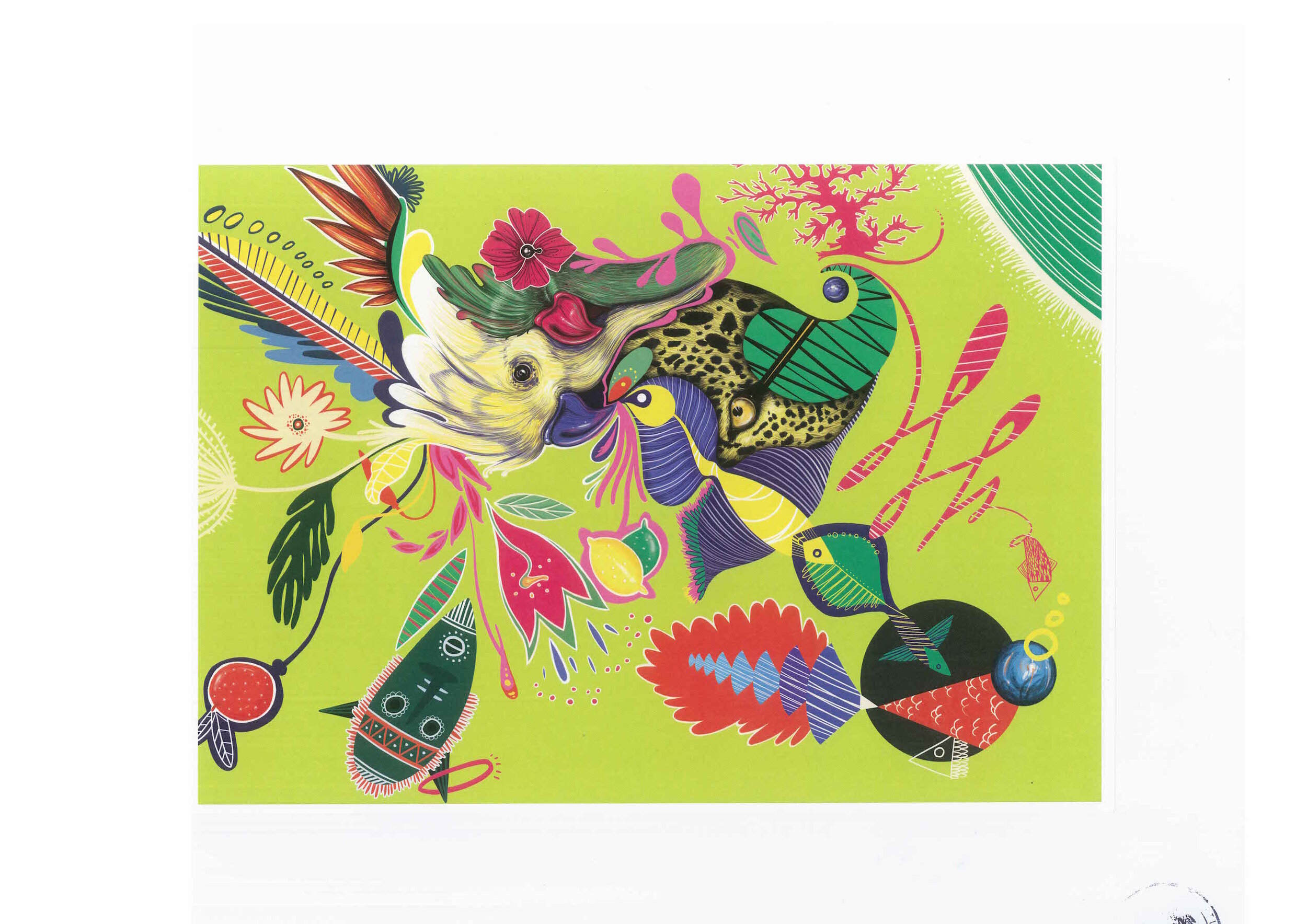

The project is linked to the Seta exhibition and the launch of Storie di seta, a collection of four new Ferragamo fragrances: Giardini di seta, Oceani di Seta, Savane di Seta e Giungle di Seta, all inspired by the maison’s history of silk print. The four fragrances share a common heart, a “silken thread” that makes it possible to combine them and create new, highly personal scents.

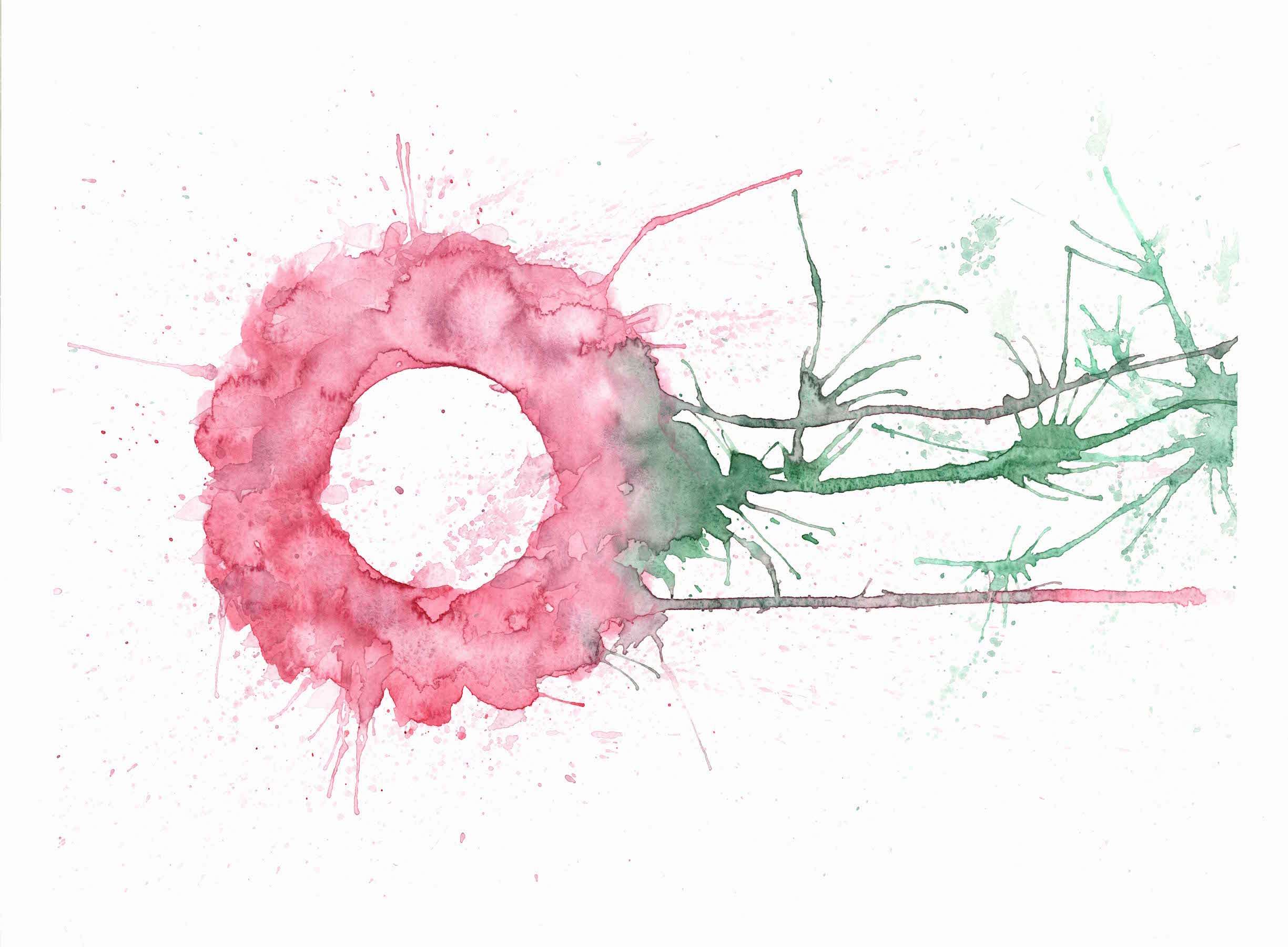

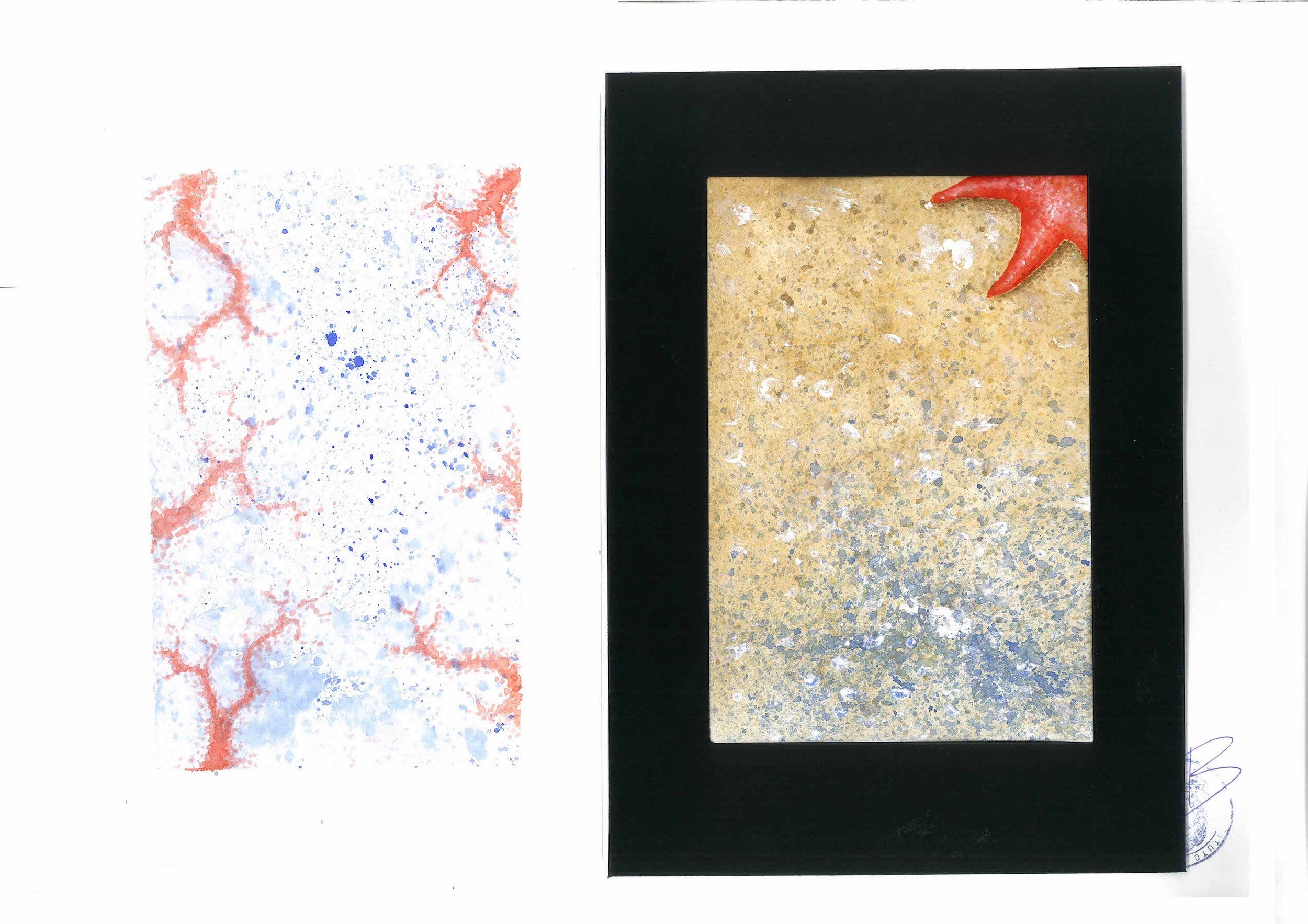

Each of these five young graphic artists have “embodied” one of the fragrances, using their preferred techniques to give them artistic form by conveying the emotions contained within each scent and their evocative reference “worlds”.

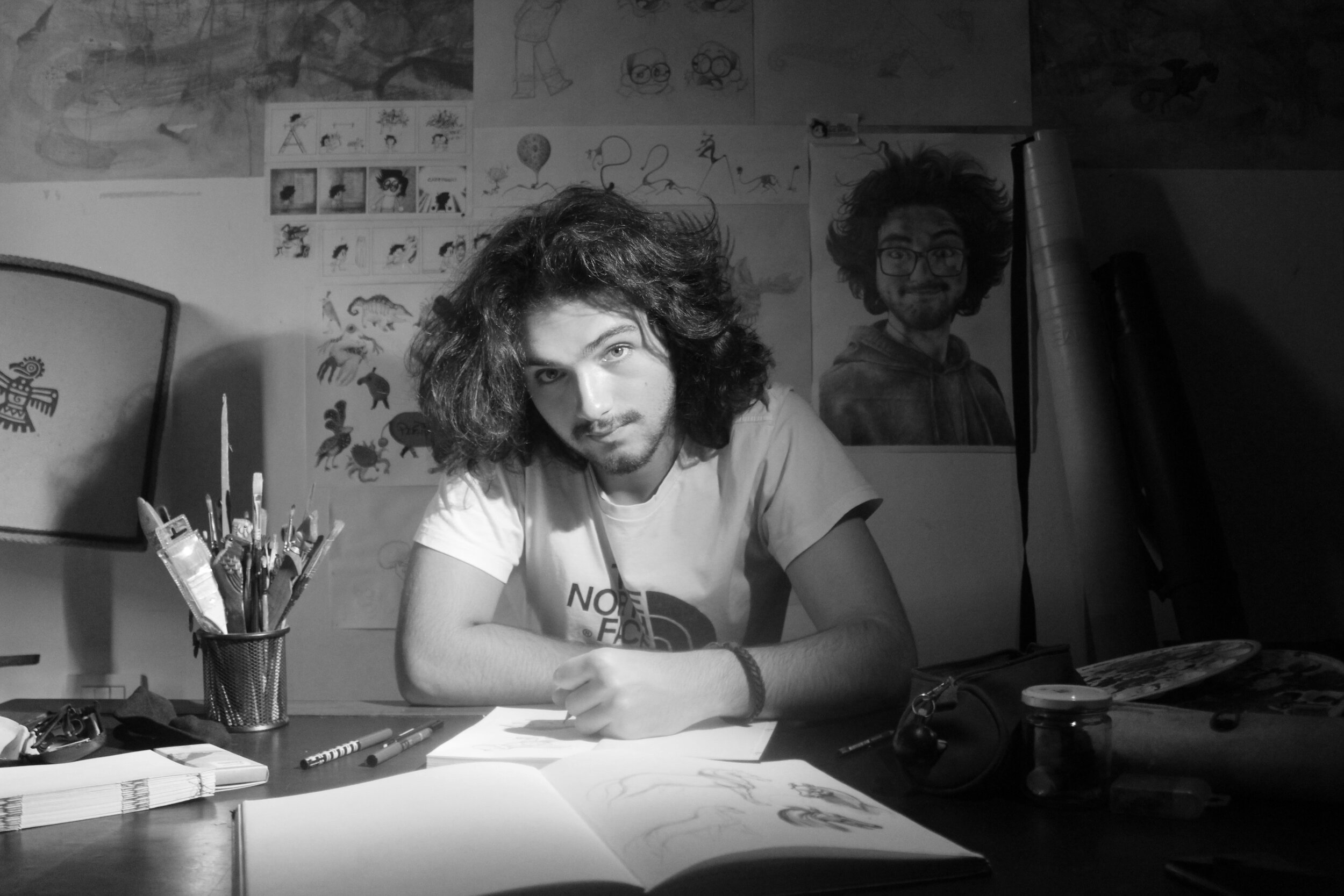

Pietro Pozzi entitled his project Metamorphosis. A feline with changing fur is the subject of his work, transformed by the “physical” specificity of the four habitats into which the perfume fragrances diversify.

Diego Emiliano Maranghi has deployed his project in four different “environments” that evoke the relevant fragrances: Garden, Water energy, Freedom has a scent, and Rewild.

Leonardo Filippini has used multiple techniques to create Symbiosis, a study that evokes the proximity between macro- and micro-universe by stimulating the olfactory memory that four scents evoke.

Marialuce Toninelli called her work Variations. Based on a rigorous design concept, she has plunged into the four detailed environments with evocative colours and multiple techniques that range from collage to painting.

Alice Bomberini has concentrated on watercolours for her work Nature, which depicts the natural worlds to which the scents make reference in a synthetic, occasionally abstract, always evocative, and highly poetic way.

This year’s project took place during a particularly challenging time, in the year of the Covid pandemic. As the results show, creativity can be a lifeline. The fashion world and all that orbits around it feeds on creative imagination and, in turn, serves as one of its sources inspiration. Fashion not only pursues the objectives of beauty, it seeks sustainability and ethics, in this case stimulating passion and research by the up-and-coming generations who will be responsible for building the future.

Section 8

Shoes

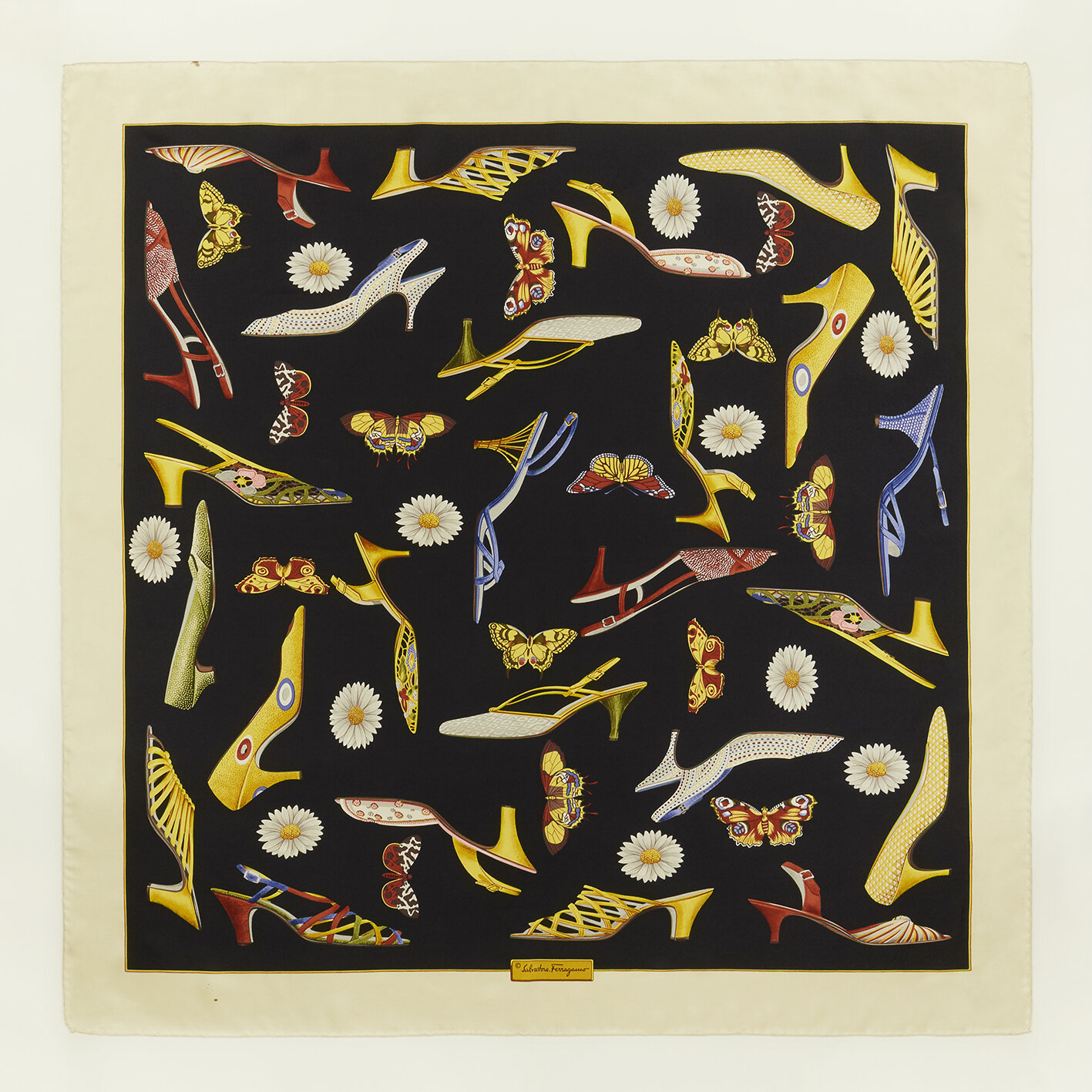

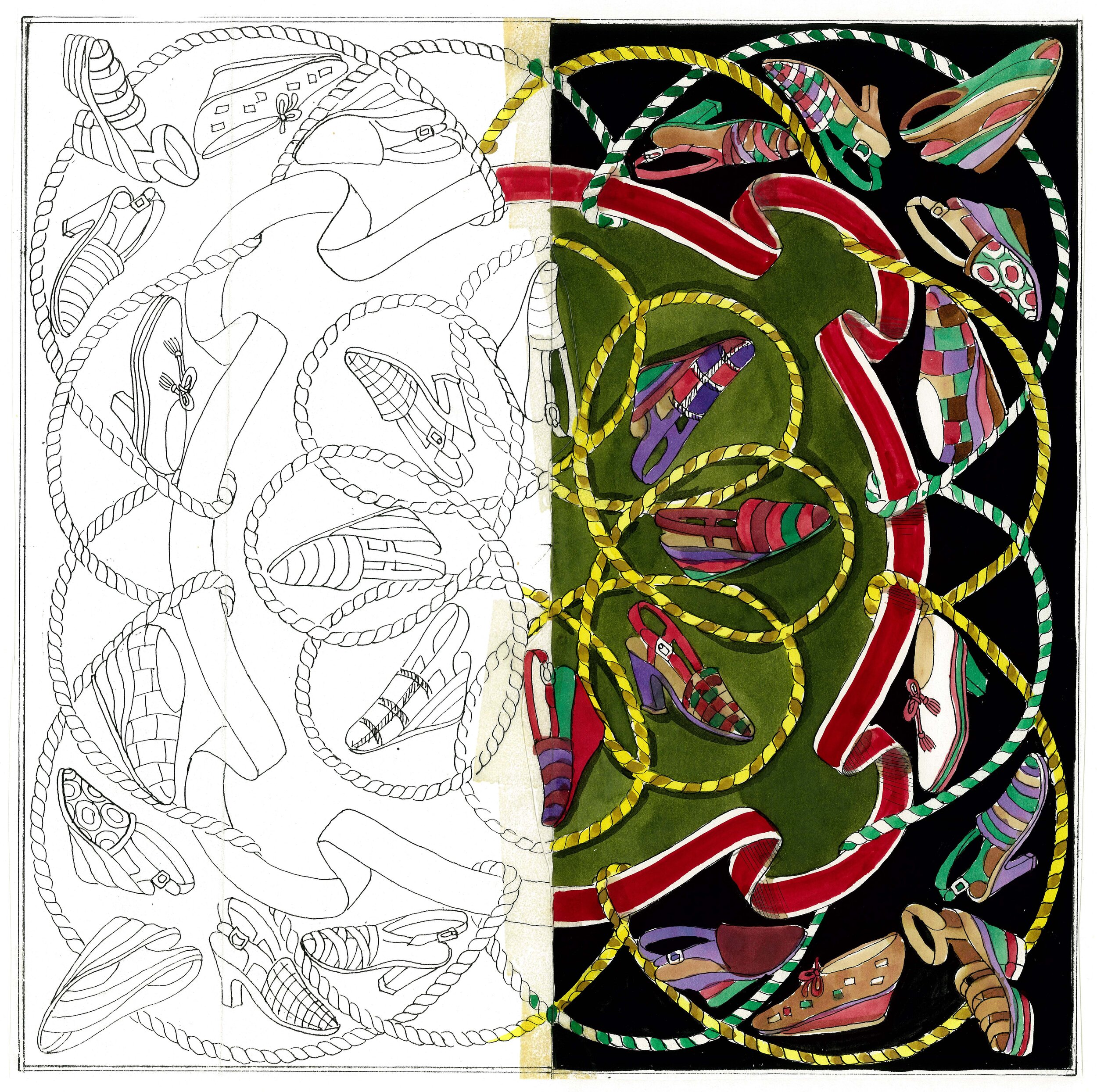

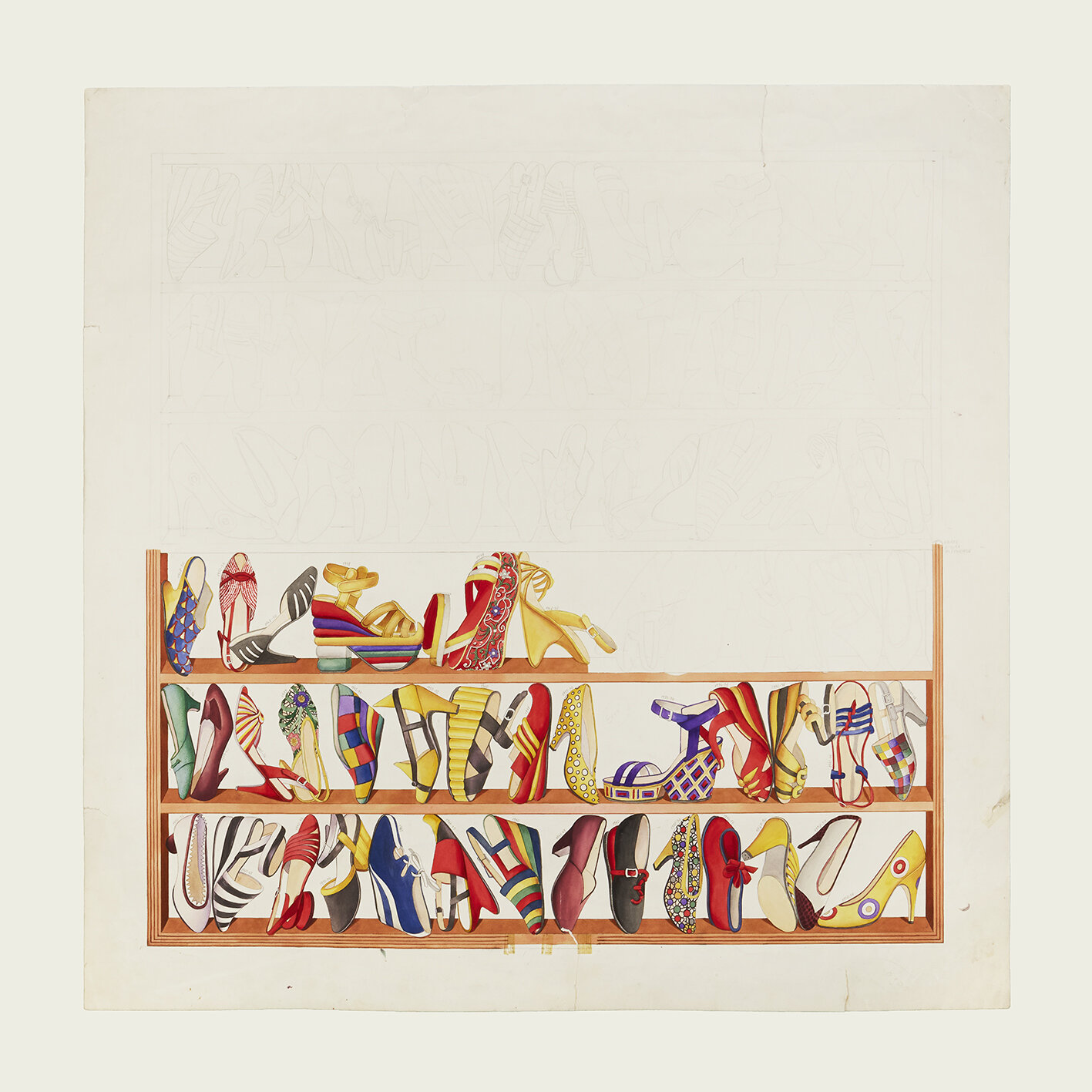

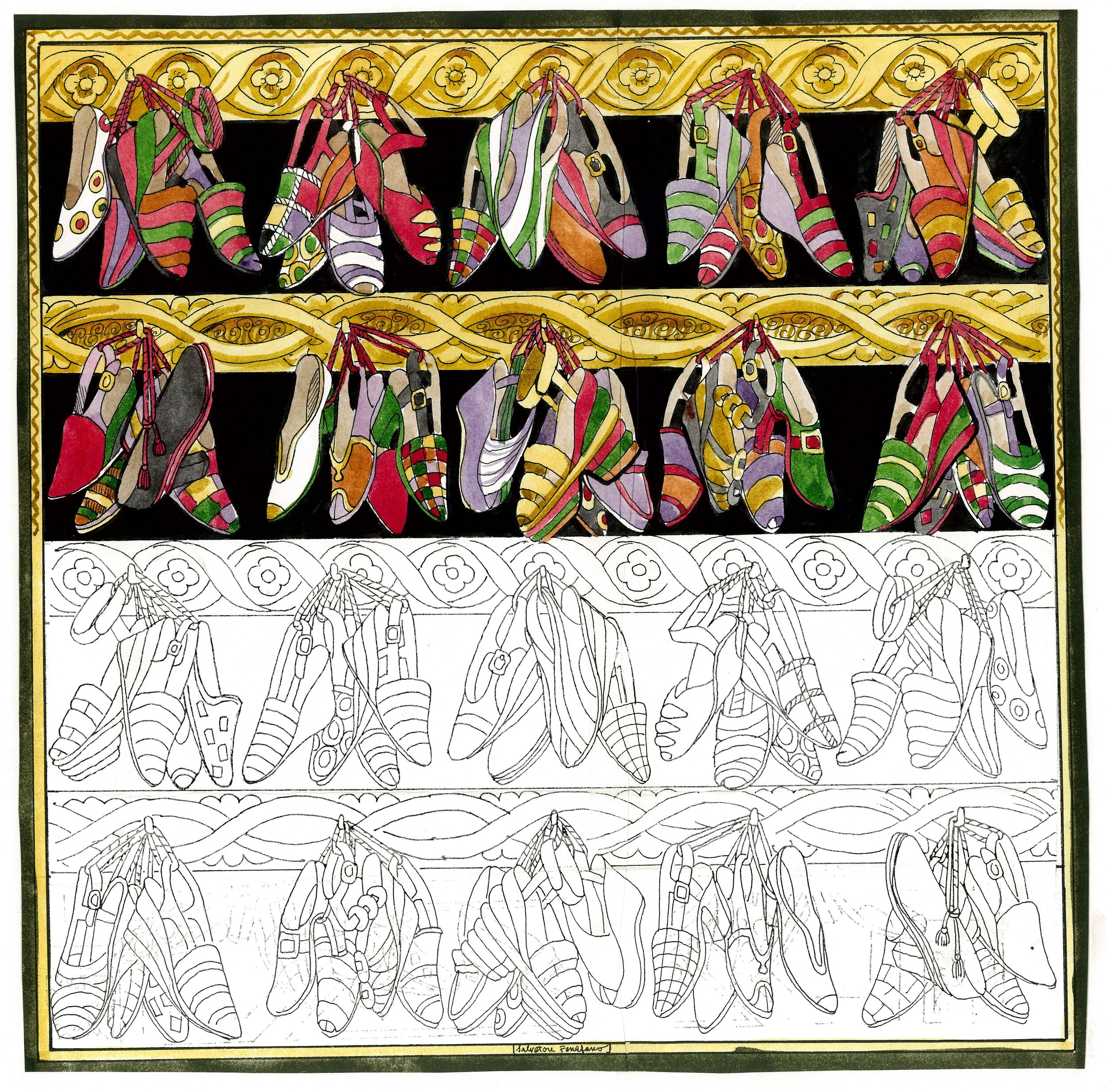

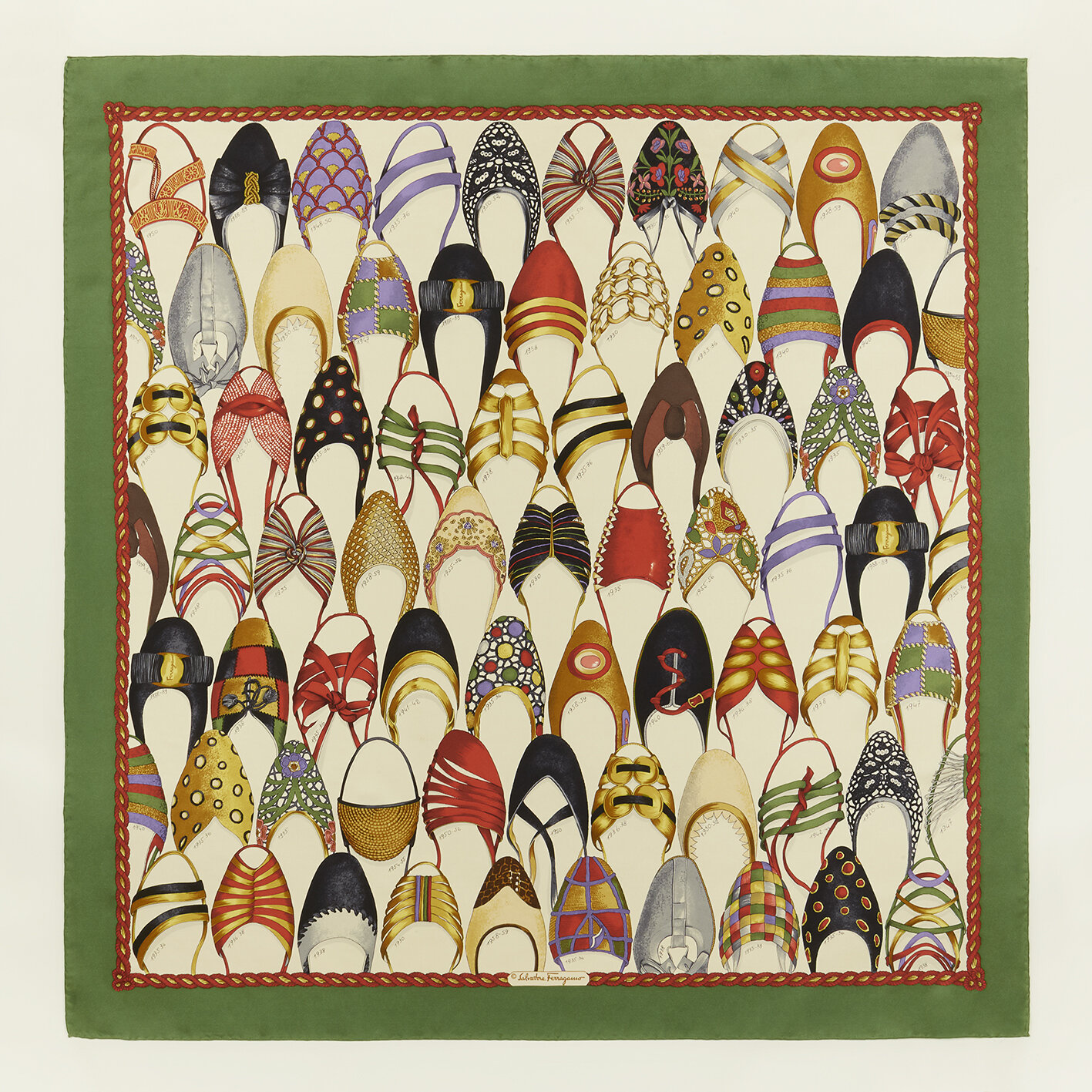

In the late 1980s, Ferragamo added a new strand to its scarves and ties: a shoe-themed creative line. This development evolved out of a hit 1985 exhibition on Salvatore Ferragamo and his creations at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, which in the following years traveled on to the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (1987), the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (1992), the Sogetsu Kai Foundation in Tokyo (1998), and the Museo de Bellas Artes in Mexico City (2006). This led to the establishment in 1995 of a permanent Ferragamo historical museum at Palazzo Spini Feroni, and in 2013 of the Fondazione Ferragamo.

The first scarf with a shoe theme was aptly called Shoes. A veritable sample of the firm’s most famous footwear, it was followed up by Toes, Bacheca, and Poster, which also features Lucio Venna’s 1930s advertising posters for Salvatore Ferragamo as decorative motifs.

Every season, a new design inspired by Salvatore Ferragamo’s famous creations joined the silk collection, thanks to the work of the specialized designers at Ferragamo design department under Fulvia’s direction. Micro-designs for ties were inspired by the uppers of his most famous shoe models, Sfera and Stella for example, or reinterpreted Tavarnelle lacework on 1930s décolletés, or Scacco, decorated with a pattern from a 1943 wooden sandal wedge.

Section 9

Decades

Central to women’s and men’s wardrobes, the scarf is an extremely versatile garment. It can be used to cover the entire head, be wound round the crown like a turban, be looped around the neck classic-style or like a negligée, be draped like a tie, folded around the waist like a belt, or draped in a triangle over a bag. By 1971, when Fulvia Ferragamo first began creating scarves with personalized, recognizable designs, the scarf was already an accessory connoting elegance, its image boosted by iconic post-war culture figures such as Audrey Hepburn, Brigitte Bardot, Jacqueline Kennedy, and Grace Kelly. The immediate success of Ferragamo’s prints prompted the Florentine maison to re-purpose these designs on a series of flowing, seductive silk garments. Since the late 1970s, Ferragamo designers have enjoyed using Fulvia’s foulard print creations on shirts, blouses, evening suits, pareos, twin-sets, and satin or nylon huskies that have been enormously successful, as well as practical and luxurious. In 1978, the geometry of Ferragamo’s “F” initial employed in the Marelle and Pied Poule scarves appeared on classic, elegant clothing.

In the 1980s, famous exotic animal designs started appearing on jacket and trench coat linings.

The following decade, scarves inspired by great Ferragamo shoes of the past, newly popular with the public after being exhibited in various locations, featured on sporty and witty garments. In the 2000s, floral prints have decorated dresses and pants with a romantic, Oriental-inflected style. At a time of renewed logomania, the Ferragamo bags’ Gancini iconic closure has become a dominant motif on shirts, trench coats, trousers, and dresses in recent collections. No thematic motif has been ignored in this silken world, the firm’s history striding the world stage in a reproduction of poses and settings from every decade.

Other Venues

Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze, Florence

A Beating of Wings. From Nature to the Library of the Tuscan Grand Dukes Curated by Simona Mammana e Stefania Ricci February 19 – April 16, 2022

A book collection of the highest order, the Biblioteca Palatina was founded by the Grand Dukes of Habsburg-Lorraine at Palazzo Pitti from 1771 until the unification of Italy. Of extraordinary value, it today forms part of the historical core of the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze. The Palatine Collection embraces a broad range of interests that reflects its universalistic approach to acquisitions. The Collection bears witness to the Grand Dukes of Lorraine’s passions and interests during the century when the dynasty ruled the Grand Duchy of Tuscany (1737–1859). Given the sovereigns’ scientific interests, it features a significant sub-collection of naturalistic studies. In the library’s books, flora and fauna are visually illustrated in a rich array of figurative portrayals. What is, to all effects, a refined naturalist’s library is contained within the wider collection, a stunning paper museum that is a distillate of the most significant scientific illustrations of the day. Indeed, it encapsulates almost entirely the origins of some illustrative itineraries.

The A Beating of Wings. From Nature to the Library of the Tuscan Grand Dukes exhibition offers a selection of many masterpiece illustrations of birds and butterflies from the Palatine collection. The exhibition documents the chronological development of the genre, placing them side by side with a number of scarves designed by Fulvia Ferragamo, triggering a dialogue based on direct inspiration or on a recognizable derivation. The images leap off the pages of the Palatine Library’s valuable books on birds by authors such as Albin, Catesby, Edwards, Manetti, Buffon, Lesson, Levaillant and John Gould and from butterflies repertoires by Moses Harris, Ernst and Donovan, evoking the vitality of a tradition expressed at its highest levels within the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Firenze’s collections.

CURRICULA

Stefania Ricci

She graduated in Literature with a specialisation in Art History from the University of Florence; in 1984 she began to work with the Galleria del Costume of Palazzo Pitti and with Pitti Immagine, curating the realisation of some exhibitions and catalogues such as La Sala Bianca: nascita della moda italiana (The White Room: the origins of Italian fashion) (Electa) in 1992 and, in 1996, on the occasion of the Biennale d’Arte e Moda in Florence, the catalogue of the Emilio Pucci exhibition (Skira).

In 1985, she curated the first retrospective exhibition on Salvatore Ferragamo at Palazzo Strozzi in Florence and its various stages at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London (1987), at the Los Angeles County Museum (1992), at the Sogetsu Kai Foundation in Tokyo (1998) and at the Museo de Bellas Artes in Mexico City (2006), starting with the organisation of the company’s archive. Since 1995 she has been the director of the Salvatore Ferragamo Museum and she has also been responsible for cultural events around the world; since then, she has curated all the exhibitions organised by the museum and the related catalogues, including Audrey Hepburn. Una donna, lo stile (Audrey Hepburn. A woman and her style) (Leonardo Arte) in 1999, Evolving Legend Salvatore Ferragamo 1928-2008 (Skira, 2008), Greta Garbo. Il mistero dello stile (The mystery of style) (Skira, 2010), Marilyn (Skira, 2012), Il calzolaio prodigioso (The prodigious shoemaker) (Skira, 2013), Equilibrium (Skira, 2014), Un Palazzo e la Città (A Palace and the Town) (Skira, 2015), Tra Arte e Moda (Between Art and Fashion) (Mandragora, 2016), 1927 Il Ritorno in Italia (Return to Italy) (Skira, 2017), L’Italia a Hollywood (Italy in Hollywood) (Skira, 2018), Sustainable Thinking (Electa, 2019). In 2019, she was appointed as a member of the Study Commission for the identification of public policies for the protection, conservation, enhancement and use of Italian fashion as cultural heritage. She has been director of the Ferragamo Foundation since 2013.

Judith Clark

Judith Clark is a curator and fashion exhibition-maker. She is Professor of Fashion and Museology at UAL, London and Co-Director of the Research Centre for Fashion Curation. Clark opened the first experimental gallery of fashion (1997-2002). Since then she has curated major exhibitions at the V&A, London; ModeMuseum, Antwerp; Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam, Palazzo Pitti, Florence; Palais de Tokyo, Paris, Simone Handbag Museum, Seoul, La Galerie, Louis Vuitton, Paris and Cristobal Balenciaga Museum in Getaria. Last year Clark curated and designed Lanvin 130 at Fosun Foundation, Shanghai; and in 2020 Clark designed the installation of Memos: On Fashion in this Millennium, at Museo Poldi Pezzoli in Milan curated by Maria Luisa Frisa. Clark runs an international multidisciplinary studio, as well as an experimental project space in London.

Sun Yuan & Peng Yu

Sun Yuan was born in 1972 in Beijing. Peng Yu was born in 1974 in Heilongjiang, China. They were educated at the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing, the city where they still live and work. They exhibited in several public and private institutions such as: 5th Lyon Biennial (2000); Yokohama Triennial (2001); Guangzhou 1st Triennial (2002); Today Art Museum, Beijing (2003); MAC Museum of Contemporary Art, Lyon (2004); Kwangju Biennial (2004); MuHKA: Museum of contemporary art, Antwerp (2004); Kunstmuseum of Bern (2005); 51st Venice Biennale (2005); Liverpool Biennial (2006); 2nd Moscow Biennial (2007); Kunsthaus in Graz (2007); Galleria Continua, San Gimignano / Beijing / Les Moulins / Habana (2008, 2009, 2011); The Saatchi Gallery, London (2008); The National Art Center, Tokyo (2008); Ullens Center for Contemporary Art - UCCA, Beijing (2009); 2nd Moscow Biennale (2009); Triennale of Aichi, Nagoya (2010); Sydney Biennial (2010); Para \ Site Art Space, Hong Kong (2011); The Pace Gallery, Beijing (2011); dOCUMENTA (13), Kassel (2012); Contemporary Art Center in Taipei (2012); Hayward Gallery, London (2012); PinchukArtCentre, Kiev (2013); Uferhallen, Berlin (2014); Qatar Museums (QMA), Doha (2016); Guggenheim Museum, New York (2016); 11th Shanghai Biennale (2016); DMA Daejeon Museum of Art, Daejeon (2017); Guggenheim Museum, Bilbao (2018); May You Live in Interesting Times, 58th Edition of Venice Biennale, Venice, Italy (2019).

Galleria Continua

Galleria Continua is a leading international contemporary art gallery, which was founded in San Gimignano (Italy) in 1990, by three friends: Mario Cristiani, Lorenzo Fiaschi and Maurizio Rigillo. Occupying a former cinema, Galleria Continua established itself and thrived in an entirely unexpected location, away from the big cities and the ultramodern urban centres, in a town – San Gimignano – steeped in history. This choice of location provided scope for the development of new forms of dialogue between unexpected geographies: rural and industrial, local and global, art from the past and the art of today, famous artists and emerging ones. Galleria Continua was the first foreign gallery with an international program to open in Beijing, China in 2004, and in 2007 launched a new site for large-scale creations – Les Moulins - in the Parisian countryside. In 2015 the gallery embarked on new paths, opening a space in La Habana, Cuba, devoted to cultural projects designed to overcome every frontier. In the course of almost thirty years Continua has created a strong identity which remains faithful to a spirit of perpetual evolution and committed to developing the public’s interest in contemporary art. That identity is grounded in two values – generosity and altruism – which lie at the heart of all its dealings with artists, the general public and its development as a whole. Galleria Continua is all about a desire for continuity between ages, aspiring to have a part in writing the history of the present and between different and unusual individuals and geographies. In 2020, its 30th anniversary year, a new space in Rome at the St. Regis Rome was opened with a calendar of didactic activities and artist residences. In the same year, a space in Brazil was also opened: Galleria Continua São Paulo, inside the Pacaembu sports complex. In January 2021, a new exhibition space was inaugurated in Paris, in the Le Marais neighborhood.

Irene Montini e Rocco Gurrieri

Irene Montini and Rocco Gurrieri are an Italian artistic duo who have been working together since 2017 creating photographic and editorial projects, films, video art, and experimental animations. They have published and crafted advertisements for Vice, I-d, Schön!, La Repubblica, Art Tribune, La Nazione, Contributor, Dazed Beauty, Sleek, Infringe, Pap, WRPD, Luisa via Roma, Nike, and Reebok. In 2019, they directed the documentary Sustainable Thinking for the Museo Salvatore Ferragamo and produced the shots for the accompanying exhibition catalogue. Incanto, their first solo exhibition at the Museo Novecento in Florence, opened in 2020. In a search for dark splendor, they draw their inspiration from a fascination with mystery, straddling the boundary between art and fashion.

Art Media Studio

Art Media Studio’s works have helped revolutionize the art of staging in cultural venues. From museum art to edutainment, fashion and retail, the Studio adopts a decidedly pop-led creative process to calibrate leading-edge technology with authentic knowledge of art history. Creative architects and video artists Vincenzo Capalbo and Marilena Bertozzi are the brains behind Art Media Studio. From its base in the heart of old Florence, Art Media Studio has won over a wide audience, earning plaudits from international critics ranging from the Immagine Video Istituzionale First Prize (Milan) to the best screenplay at the International Festival of Documentary Films on Art (Brixen Art Film Festival in Bressanone), as well as making it onto the podium at a variety of prestigious competitions, including being recently shortlisted at the Art Doc Festival of the Rome Film Festival, and winning first prize at the Festival of Audiovisual International Multimedia Patrimony in the Creative exhibition installations category.

The Studio’s ever-evolving story emancipates multimedia language from the Nineties into an immersive setting for pioneering video projects that benefit from high-level creativity. The Studio’s works have rightfully appeared at major museums in Italy and the world, from the Gallerie degli Uffizi to the Galleria dell’Accademia, both in Florence, to the Expressions Whirinaki Arts & Entertainment Centre in Wellington, the Galleria Nazionale di Arte Moderna e Contemporanea, the Landesmuseum in Hannover, the OCT Creative Exhibition Center in Shenzhen, and many other important museums.

Working with top contemporary artists, historians and art critics, Art Media Studio’s works have also joined a number of permanent collections, in the process revolutionizing the most traditional codes of museum display. Art Media Studio has already collaborated with Museo Salvatore Ferragamo in previous exhibitions.